|

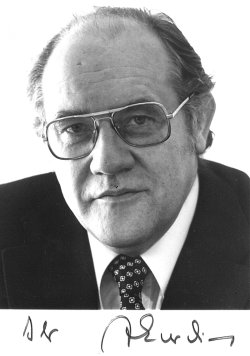

One of the most influential directors of opera in

post-war Germany,

August Everding was also an extremely competent administrator, holding

positions at the Hamburg State Opera and the Bavarian State Opera in

Munich, where he became General Intendant of all the Bavarian state

theatres. In 1984 he was considered for the post of general manager of

the Metropolitan Opera, but withdrew when he realised that in New York

he would not exercise the complete artistic control to which he was

accustomed at home.

At a time when

German opera houses were often dominated by "conceptual" directors,

Everding was an unashamed traditionalist, which did not mean that his

productions were lacking in ideas: on the contrary, his work was always

full of original touches, but they were invariably used to further the

dramatic impact of an opera. Having begun his career in the spoken

theatre, he took it for granted that the plot of a drama, however

complicated, should be expounded with clarity, and his opera production

were always models in this respect.

August Everding was born in Bottrop in 1928. Too young

to take any

active part in the war, he studied piano, philosophy, theology and

dramaturgy at the universities of Bonn and Munich. He served his

apprenticeship in the theatre under Hans Schweikat at the Munich

Kammerspiele, of which he became artistic director in 1959, and manager

in 1963. His first operatic production was of Verdi's La Traviata,

which he directed for the Munich State Opera in 1967. Later that year

he - metaphorically speaking - plunged in at the deep end, staging Tristan und Isolde in

Vienna. This was a very successful attempt at a

very difficult opera, and though he was still engaged at the

Kammerspiele, offers came flooding in from the opera houses of Europe

and America. In March 1968 Everding worked for the first time in

Hamburg, directing the world premiere of Humphrey Searle's Hamlet

(later to be seen at Covent Garden, though not in Everding's

production). Later that year he returned to Munich for Carl Orff's Prometheus, which had

been premiered some months earlier in Stuttgart.

Then in 1969 he was invited to stage Der

fliegende Hollander at

Bayreuth, a signal honour as he was only the third director not

belonging to the Wagner family to work at the festival during its

entire history. With designs by Josef Swoboda, the production was much

admired, and the same team returned to Bayreuth in 1974 to stage Tristan und Isolde.

Meanwhile in autumn 1969 Everding went to San

Francisco to direct La Traviata,

and in June 1970 he made his London

debut at Covent Garden with a production of Richard Strauss's Salome,

in which the staging, Andrezej Majewski's marvellously colourful

designs, the conducting of Georg Solti and the

performance of Grace

Bumbry in the title role all contributed to its huge success.

Unfortunately Everding did not return to Covent Garden until 1979, when

his staging of Mozart's Die

Zauberflote was equally successful. The

pantomime aspects of the opera were much in evidence, while the bogus

Egyptian priests became believable 18th-century savants and men of

letters. Everding began his enduring association with the Metropolitan

Opera in 1971 with Tristan und Isolde,

which was particularly admired

for being the first production to use the full technical resources of

the Lincoln Center house. He returned to New York in 1976 for

Lohengrin; in 1974 for Boris Godunov,

a production later seen in both

Chicago and San Francisco; and in 1985 for Khovanshchina. Nineteen

seventy-three, when he left the Kammerspiele, was a particularly busy

year: Parsifal at the Paris

Opera was followed by one of his greatest

triumphs, Die Zauberflote at

the Savonlinna Festival in Finland, which

was repeated almost every year until 1993. At the Salzburg Festival

that year he staged the world premiere of Orff's De temporum fine

commoedia ("Drama of the end of time"). In the autumn of 1973

Everding

went to Hamburg as Resident Director of the State Opera. The four years

he spent there were among the most fruitful of his career. Having

already staged Salome in

Hamburg, Everding chose Strauss's Elektra

as

his first new production, surprising everyone by his fidelity to Hugo

von Hofmannstal's stage directions in the text. This production was

taken to Paris. Next he tackled Khovanshchina,

10 years before he

staged Mussorgsky's epic in New York. After revivals of La Traviata and Tosca, in 1975 he

directed Verdi's Otello, with

Placido Domingo singing

the title role for the first time. That year a disastrous fire (started

by a dismissed stagehand) destroyed sets and costumes for 54 of the 59

productions in store. During his last two seasons in Hamburg, Everding

staged a superb Parsifal,

with brilliant Art Nouveau-style decors by

Ernst Fuchs, which remains my favourite of all his productions. This

was followed by Lohengrin and

Der Rosenkavalier. After

an interlude in

Salzburg for a baroque piece by Stefano Landi, Il Sant'Alessio,

Everding took over as Intendant of the Bavarian Opera in Munich. A new Lohengrin was followed

by Die Zauberflote (the

Covent Garden version

was a recreation of this) and a curiosity, Das Labyrinth by Peter von

Winter, whose libretto, also by Emanuel Schikaneder, is a sequel to

that of Die Zauberflote.

During his years in Munich Everding directed Die Meistersinger with

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Hans Sachs; Mozart's Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail

and Mitridate, re di Ponto;

Honegger's Jeanne d'Arc au Bucher;

another new Tristan; and

Orff's Die Bernauerin,

staged in the courtyard of the Alter Hof in July 1985 to celebrate the

composer's 90th birthday. In 1983 Everding was appointed General

Director of the Munich state theatres, which include the

Nationaltheater, the Theater am Gartnerplaz and the Staatsschauspiel.

Certain of Everding's detractors saw this as a polite way of pushing

him upstairs. Whatever the truth, during the last decade of his career

he worked a great deal elsewhere in Berlin, Cologne, Dusseldorf and

Zurich, as well as Chicago, Sydney, Buenos Aires and Warsaw. Invited by

Robert Satanowski, the Music Director of the Theatr Wielki, Warsaw, to

stage Wagner's Der Ring des

Nibelungen, with a mixed cast of German,

American and Polish singers, Everding together with Satanowski achieved

a magnificent result in only two years, 1988 and 1989. No complete Ring

cycle had ever been staged in Warsaw before; the orchestra, the public

and many of the singers were totally unacquainted with the work, but

Everding's dramatic instinct and his ability to clarify even Wagner's

most abstruse ideas triumphed. After his success in Warsaw, in 1992

Everding began to build up another Ring

cycle, this time in Chicago,

where the Ring had last been

performed in 1930. Spread over four

seasons, the production took longer than in Warsaw to complete, but in

the spring of 1996 three cycles, designed by John Conklin and

conducted

by Zubin Mehta,

were performed and rapturously received by the

audience. Everding's job was when he died was as artistic director for

the German display in the Millennium World Fair, to be held in Hanover

in 2000. August Everding was born in Bottrop in 1928. Too young

to take any

active part in the war, he studied piano, philosophy, theology and

dramaturgy at the universities of Bonn and Munich. He served his

apprenticeship in the theatre under Hans Schweikat at the Munich

Kammerspiele, of which he became artistic director in 1959, and manager

in 1963. His first operatic production was of Verdi's La Traviata,

which he directed for the Munich State Opera in 1967. Later that year

he - metaphorically speaking - plunged in at the deep end, staging Tristan und Isolde in

Vienna. This was a very successful attempt at a

very difficult opera, and though he was still engaged at the

Kammerspiele, offers came flooding in from the opera houses of Europe

and America. In March 1968 Everding worked for the first time in

Hamburg, directing the world premiere of Humphrey Searle's Hamlet

(later to be seen at Covent Garden, though not in Everding's

production). Later that year he returned to Munich for Carl Orff's Prometheus, which had

been premiered some months earlier in Stuttgart.

Then in 1969 he was invited to stage Der

fliegende Hollander at

Bayreuth, a signal honour as he was only the third director not

belonging to the Wagner family to work at the festival during its

entire history. With designs by Josef Swoboda, the production was much

admired, and the same team returned to Bayreuth in 1974 to stage Tristan und Isolde.

Meanwhile in autumn 1969 Everding went to San

Francisco to direct La Traviata,

and in June 1970 he made his London

debut at Covent Garden with a production of Richard Strauss's Salome,

in which the staging, Andrezej Majewski's marvellously colourful

designs, the conducting of Georg Solti and the

performance of Grace

Bumbry in the title role all contributed to its huge success.

Unfortunately Everding did not return to Covent Garden until 1979, when

his staging of Mozart's Die

Zauberflote was equally successful. The

pantomime aspects of the opera were much in evidence, while the bogus

Egyptian priests became believable 18th-century savants and men of

letters. Everding began his enduring association with the Metropolitan

Opera in 1971 with Tristan und Isolde,

which was particularly admired

for being the first production to use the full technical resources of

the Lincoln Center house. He returned to New York in 1976 for

Lohengrin; in 1974 for Boris Godunov,

a production later seen in both

Chicago and San Francisco; and in 1985 for Khovanshchina. Nineteen

seventy-three, when he left the Kammerspiele, was a particularly busy

year: Parsifal at the Paris

Opera was followed by one of his greatest

triumphs, Die Zauberflote at

the Savonlinna Festival in Finland, which

was repeated almost every year until 1993. At the Salzburg Festival

that year he staged the world premiere of Orff's De temporum fine

commoedia ("Drama of the end of time"). In the autumn of 1973

Everding

went to Hamburg as Resident Director of the State Opera. The four years

he spent there were among the most fruitful of his career. Having

already staged Salome in

Hamburg, Everding chose Strauss's Elektra

as

his first new production, surprising everyone by his fidelity to Hugo

von Hofmannstal's stage directions in the text. This production was

taken to Paris. Next he tackled Khovanshchina,

10 years before he

staged Mussorgsky's epic in New York. After revivals of La Traviata and Tosca, in 1975 he

directed Verdi's Otello, with

Placido Domingo singing

the title role for the first time. That year a disastrous fire (started

by a dismissed stagehand) destroyed sets and costumes for 54 of the 59

productions in store. During his last two seasons in Hamburg, Everding

staged a superb Parsifal,

with brilliant Art Nouveau-style decors by

Ernst Fuchs, which remains my favourite of all his productions. This

was followed by Lohengrin and

Der Rosenkavalier. After

an interlude in

Salzburg for a baroque piece by Stefano Landi, Il Sant'Alessio,

Everding took over as Intendant of the Bavarian Opera in Munich. A new Lohengrin was followed

by Die Zauberflote (the

Covent Garden version

was a recreation of this) and a curiosity, Das Labyrinth by Peter von

Winter, whose libretto, also by Emanuel Schikaneder, is a sequel to

that of Die Zauberflote.

During his years in Munich Everding directed Die Meistersinger with

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as Hans Sachs; Mozart's Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail

and Mitridate, re di Ponto;

Honegger's Jeanne d'Arc au Bucher;

another new Tristan; and

Orff's Die Bernauerin,

staged in the courtyard of the Alter Hof in July 1985 to celebrate the

composer's 90th birthday. In 1983 Everding was appointed General

Director of the Munich state theatres, which include the

Nationaltheater, the Theater am Gartnerplaz and the Staatsschauspiel.

Certain of Everding's detractors saw this as a polite way of pushing

him upstairs. Whatever the truth, during the last decade of his career

he worked a great deal elsewhere in Berlin, Cologne, Dusseldorf and

Zurich, as well as Chicago, Sydney, Buenos Aires and Warsaw. Invited by

Robert Satanowski, the Music Director of the Theatr Wielki, Warsaw, to

stage Wagner's Der Ring des

Nibelungen, with a mixed cast of German,

American and Polish singers, Everding together with Satanowski achieved

a magnificent result in only two years, 1988 and 1989. No complete Ring

cycle had ever been staged in Warsaw before; the orchestra, the public

and many of the singers were totally unacquainted with the work, but

Everding's dramatic instinct and his ability to clarify even Wagner's

most abstruse ideas triumphed. After his success in Warsaw, in 1992

Everding began to build up another Ring

cycle, this time in Chicago,

where the Ring had last been

performed in 1930. Spread over four

seasons, the production took longer than in Warsaw to complete, but in

the spring of 1996 three cycles, designed by John Conklin and

conducted

by Zubin Mehta,

were performed and rapturously received by the

audience. Everding's job was when he died was as artistic director for

the German display in the Millennium World Fair, to be held in Hanover

in 2000.

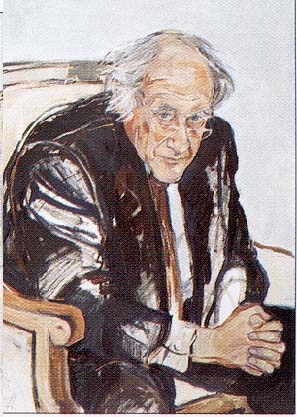

August Everding, theatre and opera director and

administrator:

born Bottrop, Germany 31 October 1928; married (four sons); died Munich

27 January 1999.

Copyright 1999 Newspaper Publishing PLC

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights

Reserved.

|

BD: When you do Tristan in several cities, is it

the same stage

setting?

BD: When you do Tristan in several cities, is it

the same stage

setting? BD: Is that too much

concentration?

BD: Is that too much

concentration? AE: One piece, no

intermission. What I don’t know is which

ending to use. We call it the hard end or the weak one. I

think the hard ending is better, but the weak one has them both going

to heaven. That’s what’s so amazing to me about Wagner – he

didn’t only compose the music and the drama, he composed the

direction. If you really listen to Wagner, you can hear in his

music what the actor has to do. He has to walk; he has to stand;

he has to wait; he has to breathe. If you really listen

– and you

have to learn to listen to the music – then

you’ll find the direction in

all of it. I think you have to change the designs; they are

old-fashioned. I’m convinced that Wagner today would have worked

a lot with films. You can hear it. Wagner was great because

he was a bastard. He behaved so badly, and now being involved

with the Ring I see it more

and more in the texts. We used to

laugh about some of the things, but more and more I see it’s a very

good text. The actions and reactions are wedded to the

music. You can’t split it all. It’s one recipe.

AE: One piece, no

intermission. What I don’t know is which

ending to use. We call it the hard end or the weak one. I

think the hard ending is better, but the weak one has them both going

to heaven. That’s what’s so amazing to me about Wagner – he

didn’t only compose the music and the drama, he composed the

direction. If you really listen to Wagner, you can hear in his

music what the actor has to do. He has to walk; he has to stand;

he has to wait; he has to breathe. If you really listen

– and you

have to learn to listen to the music – then

you’ll find the direction in

all of it. I think you have to change the designs; they are

old-fashioned. I’m convinced that Wagner today would have worked

a lot with films. You can hear it. Wagner was great because

he was a bastard. He behaved so badly, and now being involved

with the Ring I see it more

and more in the texts. We used to

laugh about some of the things, but more and more I see it’s a very

good text. The actions and reactions are wedded to the

music. You can’t split it all. It’s one recipe.