JC

JC JC: It depends; there’s a whole series of factors

including the piece itself, if it’s something I’m interested in doing, or

haven’t done and am interested in doing it. If I have done before,

am I interested in re-exploring it in a different situation with a different

director? Perhaps it’s a piece I’m not interested in, or it’s a piece

I’m not particularly interested in but I like working with the director.

That has happened because often I have not responded to pieces, but I worked

with a director that I liked very much and he or she leads me into the piece.

Then I discover things that I didn’t know were there. Sometimes it’s

the organization. If it’s an organization that

I have a tie with or feel connected to, I will work there almost as a matter

of course no matter what the piece is. Of course the trickiest ones

are new operas where you just have to go on your instinct, or rely on who

the director is. You very seldom can hear the new piece. An

exception was when I did Ghosts of Versailles

[by John Corigliano]

at the Met. They spent an enormous amount of money preparing a tape

of the whole opera, with the orchestra parts all done by synthesizer and

the full cast singing it.

JC: It depends; there’s a whole series of factors

including the piece itself, if it’s something I’m interested in doing, or

haven’t done and am interested in doing it. If I have done before,

am I interested in re-exploring it in a different situation with a different

director? Perhaps it’s a piece I’m not interested in, or it’s a piece

I’m not particularly interested in but I like working with the director.

That has happened because often I have not responded to pieces, but I worked

with a director that I liked very much and he or she leads me into the piece.

Then I discover things that I didn’t know were there. Sometimes it’s

the organization. If it’s an organization that

I have a tie with or feel connected to, I will work there almost as a matter

of course no matter what the piece is. Of course the trickiest ones

are new operas where you just have to go on your instinct, or rely on who

the director is. You very seldom can hear the new piece. An

exception was when I did Ghosts of Versailles

[by John Corigliano]

at the Met. They spent an enormous amount of money preparing a tape

of the whole opera, with the orchestra parts all done by synthesizer and

the full cast singing it.

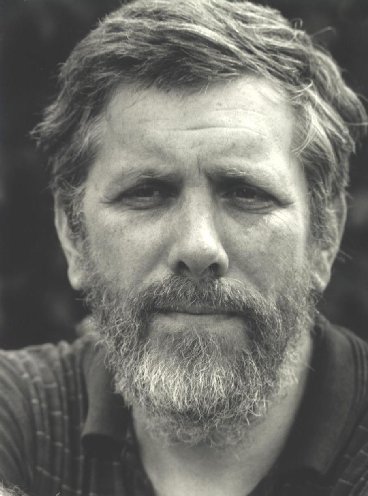

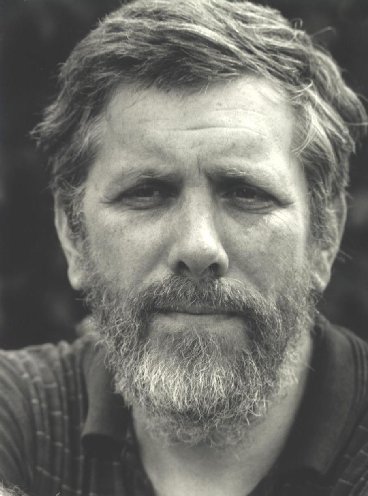

John Conklin To Take Home 2008 TDF/Irene Sharaff AwardLegendary designer John Conklin is among the recipients of the 2008 TDF/Irene Sharaff Awards. For his achievements as both a costume and set designer, John Conklin will receive the TDF/Irene Sharaff Awards' special Robert L. B. Tobin Award for Lifetime Achievement in Theatrical Design at a ceremony on Friday, March 28, at the Hudson Theatre in New York City.

Conklin first designed on Broadway as scenic and costume designer for Tambourines to Glory (1963). Other Broadway credits include scenic design for The au Pair Man (1973), Lorelei (1974), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1974), costume and scenic design for Rex (1976) and The Bacchae (1980), scenic design for The Philadelphia Story (1980), Awake and Sing (1984), and A Streetcar Named Desire (1988). He was nominated for: a 1974 Tony Award for Best Scenic Design for The Au Pair Man, a 1975 Drama Desk for Outstanding Set Design for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and a Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Set Design for the 1992 production of Tis Pity She's a Whore. At the American Repertory Theatre, Conklin has designed costumes for Robert Wilson's Alcestis (1985), sets and costumes for Sweet Table at the Richelieu (1986), sets and costumes for Robert Wilson's production of When We Dead Awaken (1990), sets for Henry IV (parts 1&2) (1993), sets for Henry V (1994), and sets for The Tempest (1995). Conklin made his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1985 when he designed the costumes for Khovanshchina. Other Met credits: scenic design for Semiramide (1990), sets and costumes for The Ghosts of Versailles (1991), and sets for Lucia di Lammermoor (1992), I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata (1993), Pelléas et Mélisande (1995), Norma (2001), and Il Pirata (2002). Conklin's extensive Glimmerglass Opera credits include: scenic design for Lizzie Borden (co-produced with New York City Opera - 1996), sets for Of Mice and Men [by Carlisle Floyd] (co-produced with New York City Opera - 1997), set design for Abduction from the Seraglio (1999), set design for Agrippina (2001), set design for Bluebeard (2003), set and costumes for The Good Soldier Schweik (2003), costumes for The Mines of Sulphur [by Richard Rodney Bennett] (2004), and set design for La Fanciulla del West (2004). His designs are seen in opera houses, ballet companies, and theatres all over the world, with designs for Lyric Opera of Chicago, Seattle Opera, San Francisco Opera, Houston Grand Opera, The Dallas Opera, Bastille Opera in Paris, the Boston Ballet, Louisville Ballet, the Guthrie Theater, Arena Stage, the Kennedy Center and the Goodman Theatre among many others. Conklin has designed many world premieres in his career, including the 1988 world premiere of Argento's The Aspern Papers with The Dallas Opera and the world premiere of The Ghosts of Versailles at the Metropolitan Opera (1991). In 1989, he was the USITT Award Recipient in Scenic Design and after the 2008 season, Conklin will retire from Glimmerglass Opera where he served as associate artistic director for 18 years.

|

This interview was recorded in Chicago on January 6, 1995.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB two weeks later and again the following year

to promote performances of his productions at Lyric Opera of Chicago.

The transcription was made and posted on this website early in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.