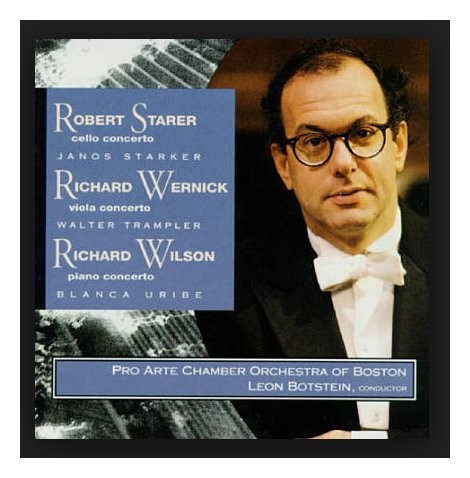

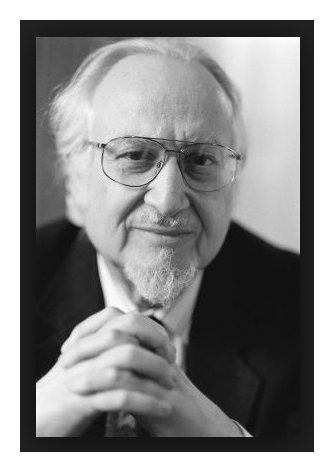

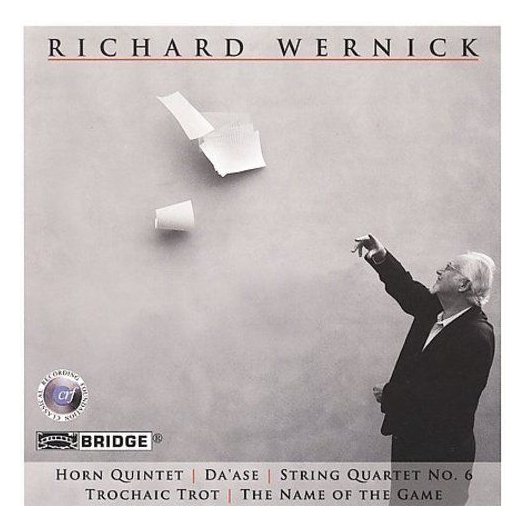

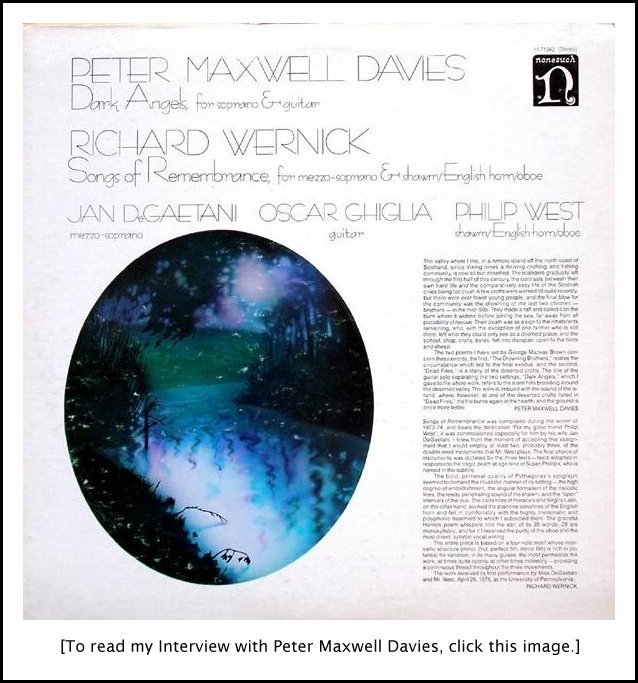

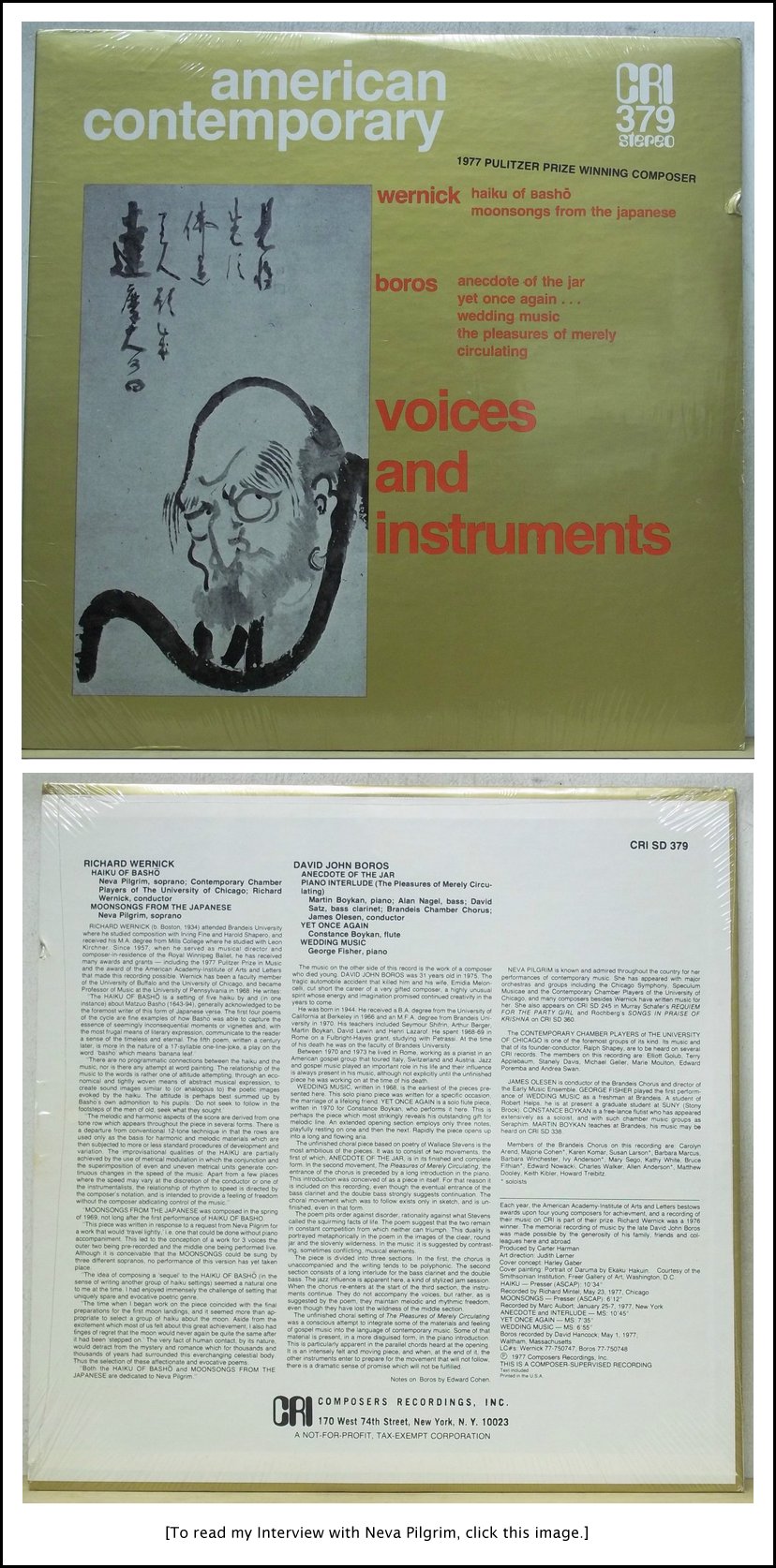

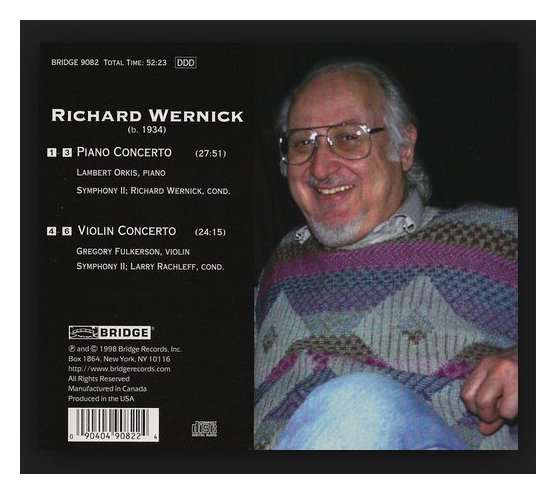

Born 1934 in Boston, Massachusetts, Richard Wernick’s many awards include the 1977 Pulitzer Prize in Music, and three Kennedy Center Friedheim Awards (First Prizes in 1986 and 1991, Second Prize in 1992) — the only two-time First Prize recipient. He received the Alfred I. Dupont Award from the Delaware Symphony Orchestra in 2000, and has been honored by awards from the Ford Foundation, Guggenheim Foundation, National Institute of Arts and Letters, and the National Endowment for the Arts. In 2006, he received the Composer of the Year Award from the Classical Recording Foundation, resulting in the funding for an all-Wernick CD on the Bridge label (released in 2008 and shown below) featuring performances by David Starobin, William Purvis, the Juilliard String Quartet and the Colorado Quartet.

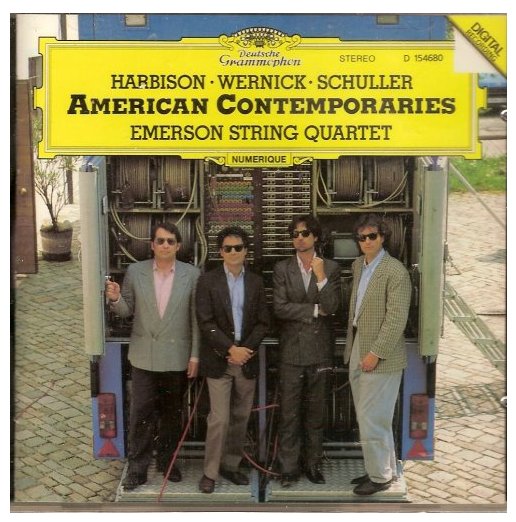

Mr. Wernick became renowned as a teacher during his tenure at the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught from 1968 until his retirement in 1996, and was Magnin Professor of Humanities. He has composed numerous solo, chamber, and orchestral works, vocal, choral and band compositions, as well as a large body of music for theater, films, ballet and television. He has been commissioned by some of the world’s leading performers and ensembles, including the Philadelphia Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra, the American Composers Orchestra, the Juilliard String Quartet and the Emerson String Quartet. From 1983 to 1989, he served as the Philadelphia Orchestra's Consultant for Contemporary Music, and from 1989 to 1993, served as Special Consultant to Music Director Riccardo Muti. |

RW

RW RW

RW

RW

RW RW

RW