Soprano Anna Tomowa-Sintow

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

This conversation was held in Chicago in October of 1985 and first

published in Wagner News two

years later. I am pleased to be able to share it again now, in

2008, on my website. Much more information and many more

photographs are currently available on her website. What

follows is the text which was given to the Wagner Society of America

for their magazine 21 years ago. The photos have been added for

this internet presentation.

=== === ===

=== ===

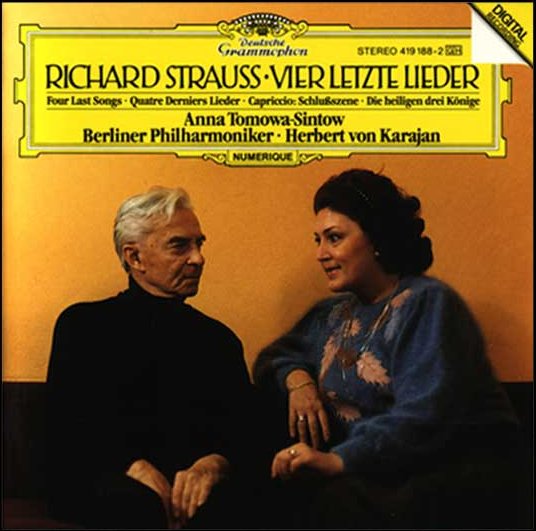

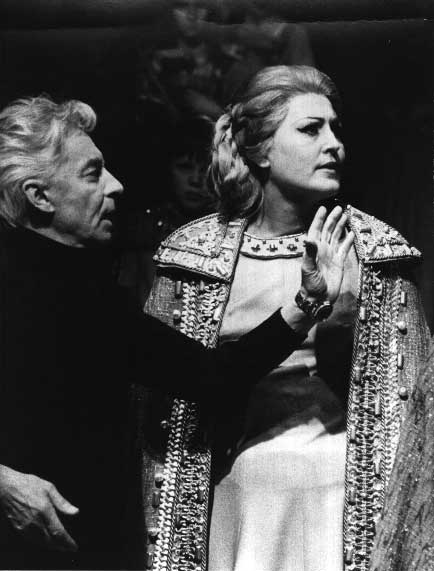

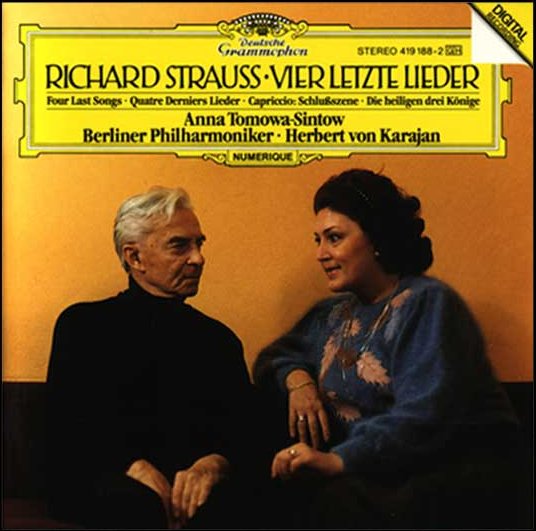

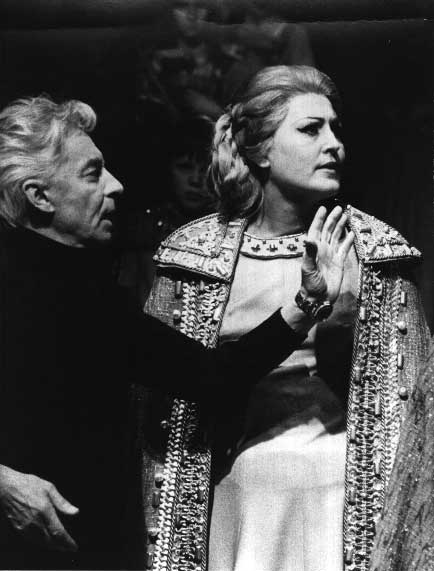

Anna Tomowa-Sintow is one of the select few artists who sings

regularly with Herbert von Karajan. She has given performances

with him of operas by Mozart, Strauss, and Wagner. Other

composers figure into her career, especially Giuseppe Verdi, and

Chicago has enjoyed her both as the title character in Aïda, and as Leonora in Il Travatore which she sang to open

the 1987-88 season. In 1985, she sang another title role,

Puccini’s Madama Butterfly in the Hal Prince production which was taped

for PBS TV. Between performances of that tragic heroine, it was

my pleasure to speak with Miss Tomowa-Sintow at her apartment.

She spoke some English, but Ursula Eggers, a top administrator with

Lyric Opera, was also there to provide a translation. It was

quite an interesting afternoon, and here is much of what said…..

Bruce Duffie: Tell me the

secret of singing Mozart!

Anna Tomowa-Sintow: There

is no secret, just a love for Mozart, and he is very well suited to the

voice. It took a little while before I started with Mozart.

In Bavaria I studied at school, and I was engaged in Germany almost

immediately after the conservatory. It took a little while before

I started Mozart. Four years after the start of my career in

Germany, Donna Anna was offered. Then came the Countess and

Fiordiligi. I was very proud to sing Mozart with Maestro Karajan

in his home-town of Salzburg, and also Donna Anna with Karl Böhm,

both

of whom/which were instrumental in introducing me to Mozart in the

proper way.

BD: What is the proper

way to sing Mozart?

AT-S: You have to have

the inner affinity and flexibility to interpret the music. The

vocal chords in the voice have to have the flexibility for the

instrumental singing. It helped a lot that I was a pianist and

had played Mozart. I was very familiar and liked the style.

But thanks to Karajan and Böhm, I got the courage to sing Mozart

not

like an instrument, but with a human voice. While Mozart,

obviously, represents so many inner feelings and has so many nuances,

it is very good to present the instrumental side of the singing.

But there has to be a human soul and that has to come out in your own

interpretation not only through clear singing, but there has to be a

personality and the soul.

BD: Did Mozart understand

the human voice better than any other composer?

AT-S: It is known that

Mozart is the best medicine for the voice. I am quite sure that

he knew what he was composing, but it is clear that it was very

intuitive.

BD: Is this what we’re

losing today – composers who understand the workings of the human voice?

AT-S: You should start and get

to know what a voice can do, but you should also know what is fun to

sing so it can come out. Even if it’s a tragedy, it should be a

pleasant experience to sing it. The style ends with Richard

Strauss and after that comes the “modern” music. You can’t forget

that Strauss’ favorite composer was Mozart and his favorite opera to

conduct was Così.

It’s something special if a composer can awaken feelings within you

that you can bring out through your own interpretation. That, I

think, is what Mozart did to Strauss in his composing. He gave

you the ideas. The general consensus is that you have to scream

and shout when you sing Wagner, and that was not really the idea of

Wagner. That’s why he built the pit in Bayreuth, which is

entirely covered. Eva and Elisabeth are sung with instrumental

lines. If you sing loud, it’s the interpretation of what comes

out of your human feelings for the part. It’s the length of the

operas of Wagner that calls for the stamina, but within the operas

there is so much lyric music and caressing music.

AT-S: You should start and get

to know what a voice can do, but you should also know what is fun to

sing so it can come out. Even if it’s a tragedy, it should be a

pleasant experience to sing it. The style ends with Richard

Strauss and after that comes the “modern” music. You can’t forget

that Strauss’ favorite composer was Mozart and his favorite opera to

conduct was Così.

It’s something special if a composer can awaken feelings within you

that you can bring out through your own interpretation. That, I

think, is what Mozart did to Strauss in his composing. He gave

you the ideas. The general consensus is that you have to scream

and shout when you sing Wagner, and that was not really the idea of

Wagner. That’s why he built the pit in Bayreuth, which is

entirely covered. Eva and Elisabeth are sung with instrumental

lines. If you sing loud, it’s the interpretation of what comes

out of your human feelings for the part. It’s the length of the

operas of Wagner that calls for the stamina, but within the operas

there is so much lyric music and caressing music.

BD: Has Wagner been

falsely accused of being a voice-wrecker?

AT-S: Yes, falsely.

Wagner wrote some of the most beautiful music to sing, but not to

shout! There’s lots of thought behind his music and you have to

really feel it, and everyone who sings Wagner has to know that and has

to interpret it. Then it’s not dangerous to sing Wagner.

The problem is whether the singer understands Wagner or not.

BD: Wagner doesn’t treat

the voice as an instrument, does he?

AT-S: I feel that the

human voice is an instrument to interpret the music through the

individual personality. I am not on the stage to represent

Tomowa-Sintow, but to interpret the role and to bring out of it what

the composer intended to do with the role. I don’t feel that the

singing is instrumental in itself, but the whole work is a work of art

and has to be interpreted as such. An example of where the human

voice was used as an instrument would be Beethoven. Each of

Wagner’s operas is a complete circle and therefore chorus, orchestra,

and soloists are one. But I doubt if he really intended to have

the voice as an instrument. For singers who are schooled in Bel

Canto, Wagner should be no problem. Strauss maybe a little bit

more…

BD: What did Wagner learn

from the Italian School?

AT-S: Rienzi is a totally Italian

opera. Lohengrin was

not done like an Italian opera; it was not copied, but it was his own

idea. The melodies just flow like an Italian opera.

Obviously, during that time when he wrote music, Wagner was inspired by

Italian opera. It’s known that lots of Italian singers sing Lohengrin. There is early

Verdi and late Verdi and Rigoletto

has nothing to do with Otello.

The same is true in Wagner. Die

Walkuüre and Die

Meistersinger are totally different from Rienzi. My favorite Wagner

opera is Tannhaüser.

It is complete, not just from the feeling, but also in thought.

It’s very human, with a theme that would, even today, be very

up-to-date.

BD: Are Wagner operas

more unified because he was his own librettist?

AT-S: It’s a question of

taste. I like the texts very much because they were felt by him,

his own feelings. It’s his idea and his thought, and very much in

line with his music. Every syllable in every word fits the music

that it’s written for. Every sigh or thought is a pause in the

music, also. Most of the stories that Wagner wrote are full of

large symbolism, and can seem to many people to be a bit

abstract. I am very much convinced about what happens within the

operas. They interpret many secret thoughts and it’s sometimes

difficult, but, like every creator, some of his libretti are stronger

than others.

BD: Are these the secret

thoughts of Wagner, or of mankind?

AT-S: They are of

mankind. When I studied Elsa, I felt that he wrote one thing, but

when you started thinking about it, there was almost the opposite

behind it. When you look at the words, they are almost worse than

Ortrud’s. Elsa wants to be good, but when you read the words

without any understanding behind it, the character seems worse than

Ortrud. Therefore you have to interpret that onstage and be very

natural about it. Just like in life, you want to be good, but

it’s not the words that count. Therefore she says her secret

thoughts. It’s like in everyday life – you can do one thing but

your inner thought is your own and you act in a different manner.

BD: Are Elsa and Ortrud

two sides of the same coin?

AT-S: Yes. They’re

both women so they have the same kinds of ways about them. After

that, it comes to the question of individual strength and

deficiencies. In ways they are very much the same, yet they are

very different. Elsa is basically weak, so she lets herself be

infected. Wagner apparently intended Elsa to be his ideal woman,

as she should have been, not having made all the big mistakes.

But she has not been perfect, so Elsa is a typical woman.

BD: So Elsa and Lohengrin

would not have been happy even if she’d not asked the fatal question?

AT-S: I don’t think

so. He comes from a world too high for her. His standing is

too high. If she hadn’t asked the question today, she would have

on another day; if it was not that mistake, another mistake would have

been made. That’s why Elisabeth in Tannhaüser is the best

representation – a woman who can,

in the end, forgive and forget.

BD: Is there any other

link between Elsa and Elisabeth?

AT-S: Yes, the

belief. For me, Elisabeth is the stronger woman. You need a

very strong woman to bring about the contrast from Ortrud, but what

Wagner gives us in the story is Elsa’s weakness.

*

* *

* *

BD: Are the productions

of Karajan more unified because he is both producer and conductor?

AT-S: There seems to be

something in Karajan that was also in Wagner. It would be very

difficult to get back from another person the same ideas or thoughts

when you are that high a level. That’s one side. On the

other side, his feelings for the music are so strong. He always

stands at the podium and wants to feel as a complete unit. So

most of his productions are very conventional and the personalities are

very close to what the music expresses.

AT-S: There seems to be

something in Karajan that was also in Wagner. It would be very

difficult to get back from another person the same ideas or thoughts

when you are that high a level. That’s one side. On the

other side, his feelings for the music are so strong. He always

stands at the podium and wants to feel as a complete unit. So

most of his productions are very conventional and the personalities are

very close to what the music expresses.

BD: Are the

unconventional productions of other producers a mistake?

AT-S: There are no

mistakes; it’s a question of what you understand in the unconventional

productions. Old-fashioned and boring I don’t like. In

modern productions where the producer thinks about the thoughts of the

composer it’s OK. What I don’t like is where you only notice the

producer. To interpret everything from his point of view and to

do something that nobody else has done before and to ignore anything

that the composer has intended just to make yourself more noticeable,

then I would rather have something more conventional – as long as it

follows the original thought of the work.

BD: How far can you

stretch the original thought?

AT-S: It’s a difficult

question. As an interpreter of the roles, I must agree with what

the role should be, and as long as it stands within that framework it

is OK. I don’t like it when the piece is put in a totally

different time-period. Maybe if it’s moved to the period when the

composer lived, that I could accept. But if Aïda is played with costumes

from Bohème, or when Forza is moved from the cloister to

an asylum, that I cannot accept.

BD: In some stagings of

the new Wagner productions, you see the figure of Wagner, himself, on

the stage.

AT-S: If it’s done well,

it could work. The only part that would really fit him would be

Tannhaüser.

BD: What about an

additional, silent character of Wagner manipulating the action?

AT-S: I would have to see

the whole concept, but it could complete the thought of the

production. It depends on how it is done. I believe in the

truth, and anything that merely furthers the importance and

glorification of the producer is unacceptable. Any opera can be

interpreted thousands of ways. That’s the phenomenon of great

art. The main thing is that you have the essence of the composer,

and everything else should serve that.

BD: Is Wagner great art?

AT-S: Certainly.

All of the well-known composers are, but you cannot compare one with

another. Each has his own way and is great in his own way.

BD: Are there are any

“standard” operas that are not great?

AT-S: There are

many. Not everything is absolutely great. When comparing

anything, there are greats and commons. Even from great composers

there are works that are great and some which are just average.

Some producers are very good with certain composers, the same as

singers and conductors. There are some pieces which are created

at a great moment.

*

* *

* *

BD: Do you enjoy making

recordings?

AT-S: I feel just awful

when I tape a recording. I don’t like microphones; they bother

me. But I learned from Karajan to keep apart from all the

technical aspects. Especially during the recording of Rosenkavalier, the atmosphere in

the studio was that of a regular performance. That is the most

important thing in a recording session, to create an atmosphere that

serves the work. You can’t just say, “Now we have to record this

piece and I must show off my nicest voice.” I prefer to record

only parts that I’ve already sung on the stage so I can interpret the

right feelings on the recording. The recording of Don Giovanni was a pure joy to make.

BD: Does opera belong on

TV?

AT-S: From an audience

stand-point, there is no comparison of what you would experience

onstage from what you see on television, but television is a great

thing for everyone in the world to experience something that otherwise

you might not experience. I’m a very big fan of Callas and it

would have been wonderful to have documentation of her because it would

serve other generations - and not just Callas, but also other

great singers and productions and conductors.

BD: To enjoy or to

learn

from?

BD: To enjoy or to

learn

from?

AT-S: Both. I never

learn just to learn. It has to be enjoyed.

BD: How are the publics

different from Europe to America?

AT-S: They are all

human. There are differences from city to city, and every singer

learns to adjust to each one. I find the American public to be

fabulous. The people are open and react very spontaneously to

anything that is beautiful. I’ve noticed that in the last few

years the audiences have become more competent, and they don’t only

wait for the large effects. They need to be engaged with what

happens onstage and they expect more all the time. They want to

be captured. It’s not just enthusiasm, but they want to

experience, and anybody onstage will realize that. You get that

feedback. You’re not just blinded by what you see, you get

involved.

BD: Does the public ever

expect too much?

AT-S: No more than what

they should actually receive! The audience always expects the

right amount, but there is a large segment of the public that is

oriented towards big names. This is not bad, generally, because

the name is not a name in itself; there is a quality behind it.

It is wonderful when the public is true to being fans of that name and

supports them. I like it when the audience expects a lot.

What I don’t like is when the audience is a little skeptical.

That’s not just for America, but for all over. If the audience

expects a lot, that’s fine. But if they have a skeptical view or

have a certain preconceived idea, that’s different. That’s what I

like about the American audience – they are very open. They are

more apt to let themselves be surprised, and the reaction is very

spontaneous.

BD: How do the acoustics

of this house compare with those elsewhere in the world?

AT-S: The singers here

feel very good, but you can judge the acoustics better from the

audience part of the house. I’m not governed by the acoustics,

however. It is well-known that at La Scala there is a special

place which has the best sound and the singers fight to stand in that

spot. That’s not very interesting, though. I would rather

stand in a spot that is not well-known and still make a big

impression!

BD: It seems

that you enjoy singing.

AT-S: That is my life and

has been since I was a very little girl.

BD: Thank you for being a

singer, and I hope you will come back here soon.

AT-S: I’m

looking forward to coming back to Chicago. I like the

high professional atmosphere here. It’s a big family of artists

and a

wonderful audience.

===== =====

===== ===== =====

---- ---- ---- ---- ----

===== ===== ===== ===== =====

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded on October 1,

1985. Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1987

and 1996. This transcription was made in 1987 and published in Wagner News that December. It

was slightly re-edited and posted on this

website in September, 2008.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

-

winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

AT-S: You should start and get

to know what a voice can do, but you should also know what is fun to

sing so it can come out. Even if it’s a tragedy, it should be a

pleasant experience to sing it. The style ends with Richard

Strauss and after that comes the “modern” music. You can’t forget

that Strauss’ favorite composer was Mozart and his favorite opera to

conduct was Così.

It’s something special if a composer can awaken feelings within you

that you can bring out through your own interpretation. That, I

think, is what Mozart did to Strauss in his composing. He gave

you the ideas. The general consensus is that you have to scream

and shout when you sing Wagner, and that was not really the idea of

Wagner. That’s why he built the pit in Bayreuth, which is

entirely covered. Eva and Elisabeth are sung with instrumental

lines. If you sing loud, it’s the interpretation of what comes

out of your human feelings for the part. It’s the length of the

operas of Wagner that calls for the stamina, but within the operas

there is so much lyric music and caressing music.

AT-S: You should start and get

to know what a voice can do, but you should also know what is fun to

sing so it can come out. Even if it’s a tragedy, it should be a

pleasant experience to sing it. The style ends with Richard

Strauss and after that comes the “modern” music. You can’t forget

that Strauss’ favorite composer was Mozart and his favorite opera to

conduct was Così.

It’s something special if a composer can awaken feelings within you

that you can bring out through your own interpretation. That, I

think, is what Mozart did to Strauss in his composing. He gave

you the ideas. The general consensus is that you have to scream

and shout when you sing Wagner, and that was not really the idea of

Wagner. That’s why he built the pit in Bayreuth, which is

entirely covered. Eva and Elisabeth are sung with instrumental

lines. If you sing loud, it’s the interpretation of what comes

out of your human feelings for the part. It’s the length of the

operas of Wagner that calls for the stamina, but within the operas

there is so much lyric music and caressing music. AT-S: There seems to be

something in Karajan that was also in Wagner. It would be very

difficult to get back from another person the same ideas or thoughts

when you are that high a level. That’s one side. On the

other side, his feelings for the music are so strong. He always

stands at the podium and wants to feel as a complete unit. So

most of his productions are very conventional and the personalities are

very close to what the music expresses.

AT-S: There seems to be

something in Karajan that was also in Wagner. It would be very

difficult to get back from another person the same ideas or thoughts

when you are that high a level. That’s one side. On the

other side, his feelings for the music are so strong. He always

stands at the podium and wants to feel as a complete unit. So

most of his productions are very conventional and the personalities are

very close to what the music expresses. BD: To enjoy or to

learn

from?

BD: To enjoy or to

learn

from?