A CONVERSATION WITH

HERMANN WINKLER

By

Bruce Duffie

Published

in Wagner News, September, 1981

Hermann Winkler is one of that very rare breed

of tenors who excel in the dramatic roles of Mozart and the lyrical roles

of Wagner. He is a member of the opera houses

in

Bruce Duffie:

It’s interesting that you are both a Mozart singer and a Wagner singer. There are very few performers today who sing both

styles successfully.

Hermann Winkler: Well, you know that until forty years ago, it was quite common to find Wagner singers who also did well in Mozart. Today there is more specialization – either Mozart or Wagner, but not both, or Italian or French, etc.

BD: Do you enjoy singing both?

HW: It is very good for the development of the voice, for the training of the voice. As the voice develops, it becomes heavier so if you are able to sing Mozart you will have good control of the lightness and flexibility, and I will keep on singing Mozart as long as my voice allows it. Later on, if the voice is not as flexible as it is now, I will stop singing Mozart and specialize in Wagner. So far, I do both and it is good for my voice.

BD: How closely do you alternate the two?

HW: I can sing Wagner the next evening after a Mozart

opera, but not the other way around. After Wagner,

I must reduce the voice which is very difficult. I

can exercise the voice in Mozart and then continue with Wagner, but if I

start with Wagner then the next day I can’t sing a Mozart role. From lighter to heavier is OK, but after the heavier

parts there must be more time – three days perhaps

– before I sing a light role again. Here

in

BD: Is that a good part for your voice?

HW: Yes, it’s a very good step from Mozart to Fidelio because there you can still keep the flexibility and the lyric part of the voice and yet you can be more dramatic. Many heldentenors think that if they are able to sing loud then they are good singers, but this is not at all correct, especially if you are brought up with Mozart.

BD: Let me ask you about the differences between staged and concert opera.

HW: I think that opera in concert form is more complicated because on the stage you can express with the voice and act while you interpret the part. In a concert performance, you just have the voice and you must stand like a statue. There is no acting at all, and I am used to expressing myself with the voice but moving also.

BD: In a concert, do you add facial expressions?

HW: No, nothing. But then

I have such a beautiful face… (Note: At this, Mrs. Winkler said, “He comes

from the

BD: Does a sense of humor help you cope with long and arduous Wagner performances and rehearsals?

HW: Yes, it’s easier going with a sense of humor, but for the performance you have it just before the opera starts; then you really don’t need anything else any more.

BD: After Lohengrin or Parsifal, are you very tired?

HW: Yes, but not so much the voice, which probably could sing another act. But I’ve been standing for four or five hours, so my feet could not stand any more!

BD: You must be an athlete.

HW: Yes, and you have to live according to such a strenuous performing schedule. You have to relax and rest ahead of time to cope with the next performance. With Wagner, the operas are much longer and I must rest more.

BD: Wouldn’t you prefer to have a few days between every performance to rest no matter what repertory?

HW: Oh well, I would prefer to have an interval of three or four days, but sometimes I have so many guest contracts and they are concentrated over a short span of time. Sometimes I am involved in several series at once, so I must sing on the required days even if it means singing one day after the other.

BD: You play the airlines then?

HW: In

BD: You sing both Lohengrin and Parsifal, and I’d like to explore their relationship. Is there a physical relationship or is it purely spiritual?

HW: Lohengrin is Parsifal’s spiritual son – they both

come from the temple of the grail.

BD: Do you feel that Lohengrin has spent a great deal of time learning from Parsifal?

HW: No, it’s just a very spiritual relationship between

the two. Anything more I leave to the Wagner

scholars. There are more discussions, especially

about the legend of Parsifal and everyone has another interpretation. If you go to Professor X from

BD: Perhaps it is simply a new generation?

HW: Yes, I agree with that. Maybe it’s just another generation. People put much more mystery in it that is actually there.

BD: At what point in the second act does Parsifal realize his mission? Does he get an inkling of it before Kundry kisses him, or does it hit him all at once?

HW: No, he is not prepared to meet Kundry because he is surrounded in Act I by the priests. Gurnemanz tells him many things, but he is not prepared to meet somebody like Kundry. It really hits him, and he gets his mission because he is hurt. He is insecure and uncertain what to do with this woman, and then he remembers Amfortas and knows he has a mission. Remember, he has never known any woman except his mother, so she is the first one he has met. His next encounter is in the scene with the flower-maidens. They touch him, physically, but when Kundry calls, he is fascinated because she was under the spell of Klingsor and she had a magic touch also on Parsifal in a certain way.

BD: How much physical contact is there between Kundry and Parsifal?

HW: The first is the kiss, and he didn’t

even know what it meant because he is the perfect fool.

It’s only in his sub-conscious that he knows he has a mission, and

therefore he thinks of Amfortas and says there’s something wrong. He must not be kissed by Kundry.

He wasn’t taught that but it’s in his sub-conscious. The only other physical contact is the washing of

his feet in the third act. Depending on the stage

direction, there might be a touch from Kundry to Parsifal when she falls

down to his feet, but this would be the director’s idea.

HW: The first is the kiss, and he didn’t

even know what it meant because he is the perfect fool.

It’s only in his sub-conscious that he knows he has a mission, and

therefore he thinks of Amfortas and says there’s something wrong. He must not be kissed by Kundry.

He wasn’t taught that but it’s in his sub-conscious. The only other physical contact is the washing of

his feet in the third act. Depending on the stage

direction, there might be a touch from Kundry to Parsifal when she falls

down to his feet, but this would be the director’s idea.

BD: Kundry must not caress Parsifal like the flower-maidens do?

HW: No, no. She catches him with words, not by physical contact. The flower-maidens are like clinging vines, but not Kundry. She is just a voice and she keeps on talking to him. She talks about his mother and all those things he knows very vaguely, and he gets more and more curious. But she is not tormenting him – only the kiss means real suffering for him, and that is how he thinks of Amfortas. During his own suffering, he remembers Amfortas and realizes his own mission. He then knows that he must get the spear from Klingsor.

BD: How do the various stage-directors manage the throwing of the spear?

HW: In

BD: How much time elapses between the second and third acts?

HW: Parsifal is not able to realize how long he has been wandering. He knows he’s been wandering around all kinds of wrong paths and struggling, but there is no mention of time. Nobody knows how long it’s been. He’s had to defend himself against enemies but without using the spear. That weapon was not for him to use.

BD: Where does he pick up the other armor?

HW: I only interpret the role as Wagner wrote it. As we talked before, there are so many interpretations, but I have studied the part closely, sticking to Wagner’s ideas. For instance, when he finally reaches Gurnemanz, he takes off the helmet for the last time. He has done this before, to rest along his journey, but we never know how many times. And when asked where he has been “all this time,” Parsifal says he was wandering around, but nobody knows the amount of time.

BD: Do you enjoy singing Parsifal?

HW: From the point of view of singing, Parsifal is very difficult for the tenor because it’s rather low – a high baritone could sing it. It lies in the middle range of the voice which is difficult for a tenor; you never have high notes! The part doesn’t take more than 25 minutes altogether, but you need lots of strength because of all the low singing.

BD: Lohengrin is much higher?

HW: Oh, yes. That part is composed much higher and is much easier for a tenor to sing. It is much longer, but easier to sing; it’s the layout that is difficult. First is the entrance and salute to the King; then an intermission of one hour, but a singer never can relax because the performance needs tension and you must keep on going to keep that tension; then the second act and the scene in the cathedral, and finally when everyone else is finished, Lohengrin is singing everything he has to sing – the duet and the farewells. But it’s all extended over five hours, and it’s the last hour where Lohengrin sings without interruption.

BD: Would you approve of a performance without intermissions?

HW: Well, it would be fine for me, but murder for the audience!

BD: During the intermissions, do you vocalize?

HW: Yes, just certain parts of what is coming – a little rehearsal to exercise the voice. Like a sportsman, once you have warmed up the muscles, you must keep on going. If you are a jogger or a tennis player, you can’t just stand there for an hour in the wind and rain and then expect to go on like before. And for the voice it’s the same.

BD: How much warming-up do you do before an opera, and is it different for the different roles?

HW: For Lohengrin I warm up for quite a while, but for Parsifal much less because if I have too much exercise then the voice gets too high.

BD: As you sing, the voice goes up?

HW: Yes. So for the difficult lower level of Parsifal, I keep away from too much vocalizing. I just try certain tones but that’s it.

BD: Is Lohengrin a complicated character?

HW: For myself he is quite a natural person, but not for the others watching him. He arrives on a swan and comes with this sword and shield so it’s kind of a fairy-tale, and so Telramund says this stranger must be a magician. The people don’t see Lohengrin as a noble person at first.

BD: Is Lohengrin a “normal” person?

HW: No. He’s mystical. He is sent by the Grail and is on a mission, but probably he’d prefer to stay with Elsa instead of fulfilling that mission.

BD: So if she had not asked him the fatal question, he would have stayed and been happy?

HW: Well, if the Elsa is beautiful… (Note: We all had a wonderful laugh at this).

BD: Is the swan in Act I the same as in Act III?

HW: Yes, he tells about one swan.

BD: Does Lohengrin know in Act I that the swan will later become Gottfried?

HW: I think that Lohengrin must have known something

about Gottfried because in most of the productions first he talks about one

swan and out of this swan comes Gottfried. So

he must be aware of this. The spiritual relationship

that exists between Parsifal and Lohengrin is continued between Lohengrin

and Gottfried. He is the heir and Lohengrin leaves

his knowledge and strength to him. It is a continuation

of the Christian belief that on one side you have the bad and on the other

the good, and there is a struggle between them. One

side has Lohengrin and Parsifal, and on the other side Ortrud, Telramund

and Klingsor. Kundry is caught by Klingsor but

she is on the good side. Wieland Wagner thought

that Alberich (in the Ring) is interpreting

the bad, the devil, and that in Lohengrin, Ortrud is the

devil. He said that Ortrud is equal to Alberich

and not so much Telramund because he is not as bad, but he is influenced

by Ortrud. Telramund is poisoned by Ortrud. From his heart, Telramund is an honest man, a correct

man, but he is always pushed by her to do things which he doesn’t want to

do. Ortrud, like Alberich, wants to dominate

the world. This is Wieland’s interpretation,

and he also carried this idea through to Otello where Iago

is the same personification of the devil. In

almost all the Wagner operas – except Meistersinger – there

is this character. Venus in Tannhauser is another. I think that Wagner did his best work in Meistersinger because all the characters are expressed in their

singing. The music is according to the character

of each person – Beckmesser, Stolzing, Sachs, Eva. There he interprets the characters by music and there

is no other opera by Wagner where the interpretation is as intense in the

music. They are more human.

(Note: At this point, I was about to probe for

more ideas concerning Meistersinger, but Herr Winkler had

to be off to another rehearsal. So I thanked

him and hoped that he would return to

(In the next issue of Wagner News, another Lohengrin – William Johns)

|

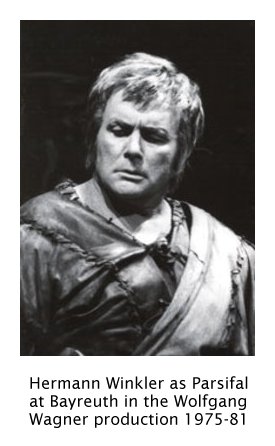

Hermann Winkler

* 3 March 1924 in Duisburg; † 21 January 2009 in Gauting Tenor Hermann Winkler was born in Duisburg and received his education at the Conservatory of Hanover. His first engagement was at the local theater in 1949 and he remained in the theater as an ensemble member until 1955. Other engagements after that were in Bielefeld and Zurich. In the years 1959-61 and 1963-66, he sang at Bayreuth Festival, initially smaller roles such as Augustin Moser in Die Meistersinger and the young sailor in Tristan und Isolde, also Heinrich in Tannhäuser and the Steersman in The Flying Dutchman. After 1972, Winkler made regular appearances at the Munich Opera Festival, especially in Mozart roles - Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni and the title role in Idomeneo. In 1976 he sang the role of Parsifal at Bayreuth, and also Don Ottavio at the Salzburg Festival. Winkler made his U.S. debut in 1980 at the Chicago Lyric Opera as Don Ottavio, and sang the same role in a 1981 guest appearance at the Deutsche Oper Berlin. Also in 1981 he participated in the premiere of the opera Baal by Friedrich Cerha at the Salzburg Festival. In Zurich Winkler sang the role of the Kaiser in Die Frau ohne Schatten by Richard Strauss and in 1987 he performed at La Scala as Herod in Salome, also in Bologna as Loge in Rheingold and on the Italian radio as Ägisth in Elektra. The season 1987-88 he joined at the Teatro Real Madrid in Wozzeck and Lulu by Alban Berg. Also in Zurich, he sang the title role in Britten's Peter Grimes, and at the Opera de Nice he was the Drum Major in Wozzeck. In 1989 at the Opera de Marseille, Winker sang Ägisth, and in 1991 at the Staatstheater Hannover he was Palestrina in the eponymous opera by Hans Pfitzner. In addition to his stage presence, Hermann Winkler was a successful song and oratorio singer. He was also decisive in establishing the Hamburg Opera Studio for the promotion of singers with talent. He made numerous records documenting his artistic range and diversity, including HMV-Electrola (Arabella), HMV ( Elektra), Edition Schwann (Massimilla Doni by Othmar Schoeck), Intercord (Coronation Mass by Mozart ), DGG (Idomeneo), Decca (Drum Major in Wozzeck), Wergo (Mathis der Maler by Hindemith). His last stage appearance was in a concert performance of Tristan und Isolde under Lorin Maazel in the Prince Regent Theater in 1999. Hermann Winkler died on January 21, 2009 after a short, serious illness in a hospital in Gauting. |

© 1980 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on December 4, 1980.

Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1994. This transcription

was made and published in Wagner News

in September, 1981; it was slightly re-edited and posted on this website

in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.