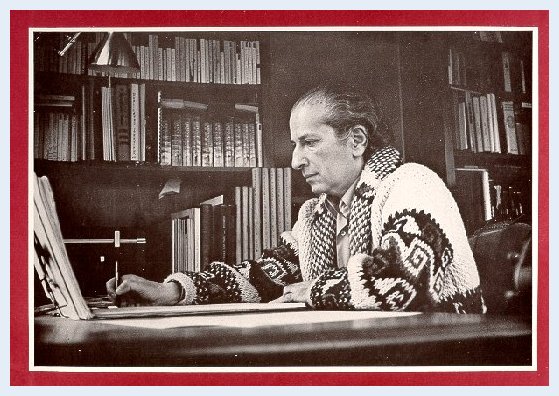

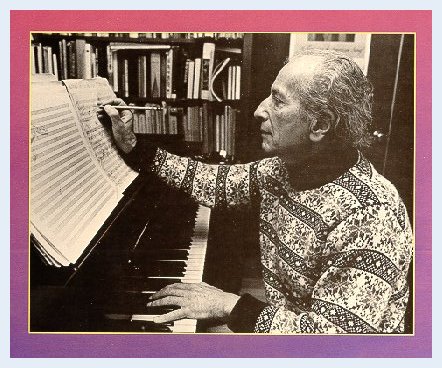

Composer Elie Siegmeister

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Composer Elie Siegmeister

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Sometimes, when I'm chatting with a musician, their joy and happiness extends to their close friends and colleagues. So when the interview is over, they make a point of saying, "Have you spoken to my friend So-and-So yet?" If I have, they are pleased to know that their pal is part of my series. If not, I immediately pounce and try to get contact information so that this new person gets the "Duffie Treatment" and is presented on the air and in print.

Such was the case with Irwin "Bud" Bazelon and Elie Siegmeister. I'd contacted Bud, and when we chatted in Chicago, he made sure that I knew of his friend Elie Siegmeister. So contact was made there, and since Elie was not planning a trip to the Windy City very soon, we had our conversation on the telephone. [Names which are links on this page refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.]

Just as Bud had told me, Siegmeister was a bubbly person and we laughed a great deal during our hour together. He gave me direct answers to my questions and was thoughtful about many things.

For details about the life of Elie Siegmeister, as well as information about the Society devoted to his life and work, see the boxes at the end of this presentation.

The centenary of Siegmeister's birth will happen in January of 2009, and this conversation from March of 1987 can help us to understand his thinking at that time of his life. Obviously, there were a few compositions still to come, and the performances of his music have continued unabated since that time. We, the public, have the privilege of enjoying the creative output of Elie Siegmeister.

Here is that conversation . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You’re both a composer and a teacher of music.

Elie Siegmeister: Yes, I’ve gone through so much teaching in the last ten years since I retired from Hofstra, but I’ve taught practically all my life up to that point, and then still do a little teaching now and then.

BD: Do you teach composition or theory?

ES: Composition.

BD: Then this is a question I like to ask composers who also teach composition, “Is musical composition something that really can be taught, or must it be innate with each young student?'

ES: Well, I think it can be taught, otherwise it would be a terrible waste of time and a big hypocrisy. You can’t make someone into a composer who doesn’t have the vocation and the drive and the ability to be one on his own, but you can shortcut a lot of the difficulties, and maybe point to some experiences that you, yourself, and other composers have had, and help shape the craft, if not the inspiration.

BD: In composition, either your own or others, where is the balance between the inspiration and the technique?

ES: It’s very difficult to say. You can’t draw a line, but there are some people who have a lot of technique and not that much inspiration. And perhaps some people have a lot of inspiration and not that much technique. The perfect balance, of course, is when you can have both.

BD: Is that what makes a masterpiece, a perfect balance?

ES: Well... In so far as words can define it, how can you go wrong?

BD: Last night when we were briefly chatting to set up this interview, you said you don’t like the term "serious composer." You prefer to use "concert music composer."

ES: Yes.

BD: Well, is popular music also music? Is rock-n-roll music?

ES: Well rock-n-roll is a popular music. It is certainly music, I suppose; I don’t particularly like most of it, I mean about 90 percent of it, 99 percent maybe. I do like some of the things that the Beatles did and the occasional other thing, but when one asks if something is music or isn’t is music, as long as you’re making it with notes, it’s a matter of taste. For a long time, many very well-known, very, very well-educated musicians used to think that anything before Bach was quite primitive and not terribly interesting. This goes back fifty years, maybe, when I was a student, but nobody paid much attention to Josquin des Prez and...

BD: Machaut?

ES: Yes, Machaut and to the music of other civilizations. That has changed, so it’s a matter of judgment there. A lot of things I hear I say I don’t know why they bother to play it, but maybe some people feel that way about my stuff. [Laughter]

BD: Well, do you write for a certain public? For whom do you write?

ES: That’s a very interesting and moot question. Certainly, many of my compositions are written for a public. There’s no shadow of a doubt. Maybe most of them, maybe all of them. I would hope that what I write will mean something to the public out there, to listeners. I’ve had, you know, many gratifying experiences when many things might have been played. The public seems to respond, so I guess it’s written FOR the public. There’s some times you don’t think about whom you’re writing it for, you just write it because you’ve got something to say or you want to get it out there. I guess there are elements you write for yourself, you write for your loved ones, you write for your colleagues, you write for the public.

BD: I assume the critics, then, are way down at the bottom of the list.

ES: Ha! No, I don’t write for the critics! [Laughter] That’s a categorical statement. There are critics who have liked my music. Some of them have been very nice to me, and others quite the other way around. But in any case, I certainly don’t write with critics in mind.

BD: Have you basically been pleased with performances you have heard of your work?

ES: Yes. Yes, I would say very largely. There have been a very minimum of performances that I would say distort the work or that you wish you didn’t have that performance. That happens very seldom. And not only have I been pleased, I’ve been ecstatic very often about the performance of my work.

BD: What about the recordings? Are you basically pleased with the way they have turned out?

ES: Oh, yes, yes. Maybe one or two could have been engineered better, or maybe the microphones weren’t placed just right, or a couple of places maybe I would have done it a little bit differently - when I wasn’t around - but I’d say more than 90 percent I’ve been very happy with the recordings. Many I was there, you know.

BD: When you’re there for recordings or for performances, do you make suggestions to the conductors?

ES: If they ask me.

BD: But basically you let them get on with their work?

ES: Well, generally. If you have a conductor who knows his business, he may call you in beforehand and ask what I have in mind in a particular place, say a sforzando, do I want a sharp accent or a broad accent. They will go over it and ask you certain things, and you answer to the best of your belief. Sometimes they don’t call you; they just play the piece and you come to the rehearsal. Almost always he'll ask you afterwards, “What did you think? Have you got any suggestions for the next rehearsal?” Once in a while you meet one who doesn’t, but those who really are musicians and have confidence in their work almost always ask the composer to go through the score with them. For example, when Stokowski did my First Symphony, which was many, many years ago, he said, “That’s rather interesting. Now come on," and I had to write down plenty of little things, ranging from, “the bassoons should be marked mezzo forte instead of mezzo piano," to, "Could you put the accent on the fourth beat instead of on the third beat?" All kinds of little things like that. And I felt the third movement was just a little bit too fast, so I asked Stokowski if maybe it could get a little more serenity and calm, and very often the conductor would say, “O.K. Fine.” [Laughter]

BD: Impressive, coming from such an imposing podium figure. Have you another conductor-story?

ES: I had one challenging experience maybe seven or eight years ago. Sergiu Commissiona, who had commissioned my Fifth Symphony, was rehearsing it with the Baltimore Symphony, and at one spot I felt that I had gone on too far. I wanted to make a cut, so after the rehearsal I went up to him and I said that, “Since you wanted to see my advice, cut these four bars after letter Q (or whatever it was). So he looked at it carefully and said, “Hmmm, let me see. You’re the composer, but if I were you I would keep bars one and three. I think those are very important bars and I think it gives a very definite impact to the work. But I think you’re right; maybe cut bars two and four." Then he said, “As long as you’ve put up with something to cut, something crossed my mind. Hold on to your chair, but what would you think of cutting from O to P?” which was about twelve bars. [Laughter] He said, “Now, don’t do it if it doesn’t strike you as being right, and you brought the whole subject up, for that matter.” So I listened to him, and I said, “Well, let’s think about it.” The next rehearsal was the next day, and he asked, “Think you might know something by tomorrow morning?” I said, “I think I might. Let me think about it.” So I went home and went through the score very carefully about twelve times. I read it through with those bars in and I read it through with those bars out, and finally I came to the conclusion he was absolutely right. So I cut those bars, and they are not in the score anymore. He was very charming the next morning. He had asked me to call him at 8:30, and 8:15 the phone rang and he said, “Listen, Elie, what did you ah, decide about the cuts?” So I told him that he was right, and I’m cutting those bars. There were going to be two performances, so he said, “Tomorrow night, why don’t I play it with the bars in, then the next night I’ll play it with the cut and then you can decide which one you want.” I said, “Oh, no! No, no. Never play those with those bars in; those bars are really out! I don’t want to ever see them again." [Laughter] So, you know, that’s one of the things that happens every once in a while.

BD: Well, a hundred years from now you don’t want a historian

then coming by and looking through your waste basket and putting those bars

back in, do you?

BD: Well, a hundred years from now you don’t want a historian

then coming by and looking through your waste basket and putting those bars

back in, do you?

ES: [Laughs heartily] No, no, no, no. Oh, I’m not even going to tell them which bars they were.

BD: This is all, of course, before the first performance. Do you ever go back and revise a score after the premiere or after publication?

ES: Ah, yes! Almost always! I don’t think there’s ever been a piece of mine where I haven't done that. I can’t remember, but it seems to me that I’ve always made some changes after the performance. Sometimes it's small changes, like taking one note out of a chord or making instead of two quarter notes a dotted quarter and eighth, or something very tiny like that, and other times it's rather important changes, mostly involving cuts because I’m a great man for cuts. I think less is more.

BD: You’re not, you’re not going to the Webern extreme, though, are you?

ES: Uh, no, no, no, no, no. Don’t worry about that. [Laughs]

BD: Well, when you start to write a piece, are you conscious of how long it should take to perform?

ES: No. No, I haven’t the faintest idea.

BD: Then when you get to the end of a piece, how do you when you’ve finished writing?

ES: That’s a very good question. How do you know anything? I mean, how do you know whether you want that piece, or where it should go, or whether this note should be that or the other thing. It just comes upon you. Generally, when I’m working at something and go over it and over it and over it and over it until I’m going stark-raving mad, at that point I know. There’s where it ought to go and that’s it. Then I have a very strong conviction, that’s it. I can’t tell you how or why I arrive at that, and it may be different in each case, but there it is.

BD: Do you work on one piece at a time, or do you have several projects going at once?

ES: I generally work on one piece at a time. I may sometimes have a project that I start and for some reason or other put aside. Maybe I didn’t like the way it was going and I wanted to give it a rest for awhile, so I start on something else; or maybe I get a commission and they want it in a hurry, so I put the first one aside and come back to it later. I do keep three or four sketches of the more or less amorphous little things lying around on the piano that someday I could pick up and make another piece out of them.

BD: What about that cut you made for Commissiona? Might that show up some place in another guise?

ES: I think you like that cut. I related that story to Benjamin Lees, and at the end he said, “My goodness, you’re really very, very relaxed about cutting your music. I know some composers, boy, if you touch one note they would howl bloody murder." I said, “Well, you see, I’m not that adverse to cuts because my father was a surgeon." [Laughter] I really believe that! I really believe that. He took out tissue that wasn’t good and I’m doing the same thing!

BD: So you’re a musical surgeon, then?

ES: In a way.

BD: Do you ever do surgery on other people’s music, or just your own?

ES: Oh, no, no, I don’t touch other people’s music. They can do their own. Sometimes, when I had some students, I would say, “I think this is too long; you might think of cutting.” Or sometimes I might say, “It’s too short, develop it more!” But that’s with students. They come to you to get your feeling about something and to be honest about it you have to give it to them.

* * * * *

BD: You’ve also done some conducting of your music and also of other music?

ES: Yes, yes. I had an orchestra for fifteen years at the university where I taught. It was a community orchestra that did a lot of everything - old music, new music and what-not.

BD: Well, my question is this: Are you the ideal interpreter of your music?

ES: I think other people ought to say. I like the way I do it, but I also like the way some other people do my music. There are some conductors who have done my stuff who are much better conductors than I am. I never pretended to be a Toscanini or a Stokowski or Maazel or somebody like that. They are master conductors. Other conductors will just ask me what I want all the time, but I wouldn’t say that I could conduct it better than they did. I think they were marvelous, although I do like the way I conduct my pieces. About a week or two ago, I had a chance to do the Western Suite which I wrote more than forty years ago, and I think it went off very well. Other people told me the same thing.

BD: So you feel that the music that you wrote a long time ago has stood up?

ES: A lot of it, yep. Some of it has hasn’t stood up because it got kicked out! [Laughter] But I’m not one of those composers who say, “Oh, no, I wrote that part years ago; I don’t like that in.”

BD: When you come back to it forty years later, do you still tinker with it?

ES: No, no. I may tinker for a little while, but after a certain period of time, that’s it. Although, some years ago I did look at some of my earlier work and I made some revisions. But once a thing is published, then forget it. That’s it, and go on to the next.

BD: Speaking of the Western Suite, that’s the one that Toscanini conducted in 1945. Was that a special thing for you? Did that give you a bigger stamp of approval to know that Toscanini had chosen your work?

ES: Of course! It was a fantastic stamp of approval.

Suddenly people began to sit up and take notice. As a matter of fact,

I think I got the most fantastic review I’d ever had up to that point in

the old New York Herald Tribune from Virgil Thomson, who really

saluted it in glowing terms. It was kind of breakthrough, because up

to that point not very much of my music was published. I had had a

few pieces published, and the day after the performance by Toscanini and

the review by Virgil, three publishers called me up and wanted the score.

[Laughter] That doesn’t happen every day.

ES: Of course! It was a fantastic stamp of approval.

Suddenly people began to sit up and take notice. As a matter of fact,

I think I got the most fantastic review I’d ever had up to that point in

the old New York Herald Tribune from Virgil Thomson, who really

saluted it in glowing terms. It was kind of breakthrough, because up

to that point not very much of my music was published. I had had a

few pieces published, and the day after the performance by Toscanini and

the review by Virgil, three publishers called me up and wanted the score.

[Laughter] That doesn’t happen every day.

BD: Was his performance of that music better than later performances? Did it have something special in it?

ES: I think so. The piece had a lot of earthy, touchy quality about it, which is, I think, one of the characteristics of a great deal of American music. There is a kind of lusty feeling, with sometimes a roughness, a harshness, or whatever you want to call it. The old man had this incredible knack of making a chord in the orchestra - it was 89 or 96 instruments, whatever there were - sound like a string quartet. It was so beautifully in tune and clean and elegant, so I think that was an amazing combination of the qualities in the score and then the qualities that he added to it. I still have a tape of that, by the way, and every once in awhile I drag it out and I’m quite thrilled by listening to it.

BD: Speaking of recordings, what do you feel has been the impact on either the performers or the public of this proliferation of commercial recordings that are now available?

ES: Well, it makes an awful lot of music available. When I was ah, starting out, there weren't many. All that you could get were Beethoven, Bach and Brahms. Maybe once in a blue moon, some lesser-known classical composer, but you didn’t get any contemporary music. Now the sky’s the limit; you can go to the public library or university library and get records of practically anything.

BD: At what point does it become too much?

ES: That’s a cultural, historical question. It’s very, very hard to say. In a sense it brings up the whole question of “What are we going to do with all the composers that we have today?”

BD: OK, then, what are we going to do with all the composers we have today?

ES: Thaaaat’s a problem. It’s one of these ironies and contradictions of what we call the free enterprise system. Here we’re turning out in all these music schools and conservatories - THOUSANDS of composers - and there isn’t room for that much! There’s room for very little. What are all these guys going to do?

BD: Does this foster competition amongst them?

ES: There is furious competition, yes. It’s a wild orgy of competition. The problem is who is to say they’re too many, they’re too much when you might get a little lone Charles Ives in Oshkosh or Columbus, Ohio, or down on the Tennessee River, and some other guy might feature composers that nobody knows about, because, as you very well know, being a good composer doesn’t mean anybody knows about you while you’re around. And that doesn’t mean that if you are a good composer people DON’T know about you. It’s a gigantic raffle. Obviously I’ve met a great many composers. Some are great big personality kids with a glass in hand and they get around. They know how to sell their wares. And then there are some guys who are just as good, maybe better in many cases, who are very sharp, but they don’t know how to go out in the hurly burly and convince everybody that their thing is the greatest stuff around. So it’s a very difficult problem.

BD: How much do you get involved in the business of selling your music?

ES: A certain amount. I‘m not gonna claim that I am completely indifferent to it. No! I try to go around, and where people might be interested in what I have, I try to make them aware of it. They ask me for it or I show it to them and send them a score. I don’t keep doing it all the time, but I certainly don’t object to it.

* * * * *

BD: I read that in 1939 you formed the American Ballad Singers. What inspired this?

ES: Well, as you probably know, the 1930s were a great big time of discovery or rediscovery, or renaissance, whatever you want to call it, of the American folk tradition. I don’t guess you were around too much in those days. I don’t know how old you are, but from the sound of your voice, maybe you weren’t around. But it was a time when a certain number of musicians, or even non-musicians began to be aware. ”We’re got this great background of wonderful stuff out there. It's exciting and we ought to know about it! And it’s our own!" It gives us a certain background, a foundation, or roots to the way American music might go. I’d say, towards the middle of the thirties there were a few balladeers, folksingers like Burl Ives, and later Woody Guthrie, and still later Pete Seeger, who went around singing these things. And I got the idea: when I was in my teens, there was a group that used to come to New York from London called The English Singers, and they brought, for the first time to my knowledge, English madrigals, and it was a great thrill and a great discovery. There were six people and they sat around a table singing these things in a rather informal way. So I got the idea, “Why can’t we do that with the American stuff?" I scouted around and found some singers in the opera who were interested, and I found this group to publicize and make people out there aware that there are these treasures from American folksong. I was very fast and free as a composer in making my own arrangements for the group. I wasn’t attempting to be authentic or scientifically musicological, but I just felt that programs of these things presented by really quite crackerjack singers, who know how to put it over, would be interesting. And, in a sense, it proved to be that. In other words, I organized a group; we gave a concert at old Town Hall in New York and it was really very successful. All the newspapers came out - I think New York then had ten newspapers, and we got seven or eight really smashing reviews. Subsequently, I toured with the group throughout the country, and gave three or four hundred concerts. We played Chicago and Detroit and San Francisco and God knows where else, and ended up in lots of little towns. The reviews were all always, “This Mr. Siegmeister and his group, American Ballad Singers, have opened our eyes to a great treasure of American music that proved to be unique and characteristic and full of play,” and things like that. I’ve got huge bundles of reviews. So that was my idea.

BD: Did you know at once that this would work better than forming say, the American String Quartet or the American Piccolo Duo, or something like that?

ES: Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha. I enjoyed being with the singers. They were very lively people and we had a lot of fun going out on the road.

BD: Tell me about working with the human voice. What is special about it?

ES: I feel that the voice is the most human of all instruments and it brings to the listener, to the public, the wide range and depth of human experience both tragic and comic; the profound depth and the superficial. It shows, I think, various aspects of our human experience, especially, in my particular view, the American experience. Besides the ballads I arranged, I’ve written a great number of solo songs, and I tried to find that in my own composing for the voice. I would try to find the life and death and love and hatred and bitterness, but mostly with an American slant. I think about 90 percent of my songs are to words by American poets.

BD: So that’s very special for you, then.

BD: So that’s very special for you, then.

ES: Yes, very much so. One poet who’s not an American that I’ve always felt very strongly about is William Blake. I started with him when I was very young and I’m still going on his stuff. But almost always it’s an American poet.

BD: There’s something else I want to touch on a little bit: You helped to found the American Composers Alliance. What was this designed to do, and has it done it?

ES: In the 1930s, being a composer was much tougher than it is today. Even if you had what’s called a hit - I mean something that everybody liked and so forth - what were you going to do with it? Where’s it going to go and how are you going to live? At that point VERY FEW of the important publishers or recording companies would even consent to listen to an American work. Nobody wanted that, "It won’t sell." Something German or French or Spanish, yes, they’d be interested, but ... So I felt that if the composers were to get together and try to make some kind of an agreement amongst them with the performing outlets, whether concert or radio in those days, then maybe we could help ourselves. I knew many of the composers who were around. I went to Roy Harris and Douglas Moore and Copland and many of the others, and they said, “It sounds like a GREAT idea! Yeah, let’s do it!” So we called a meeting and I was asked to be the secretary and draw up the constitution and bylaws. Copland was the most prominent person, so they asked him to be the president. It was tough going for a number of years because everybody said, “Oh, American music! Who wants it? Who wants that?” and “Why should we pay money for them? If we’re going to give you a performance you ought to get down on your hands and knees and be grateful forever. Don’t ask us for money." So we went along and soon we approached the performing rights societies. ASCAP [American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers] didn’t buy it, but BMI [Broadcast Music Incorporated] gave us some money. In those days BMI was trying to make inroads and we got a few dollars here and a few dollars there and so forth. The ACA [American Composers Alliance] was started and is still going. Subsequently I found that most of the publishers who were becoming interested in my music would not take a work unless it was an ASCAP work. In those days there were not that many BMI publishers, so I joined ASCAP in 1952 and have been a member since then. As a matter of fact, I have been on the board of directors since 1977, and they just elected me chairman of the Symphony and Concert Committee. ASCAP does very well for the composer. I’m sure BMI does, too, and ACA does likewise, but I think ASCAP has become the big thing. But I think the existence of the ACA prodded ASCAP into recognizing the importance of concert music.

BD: When you have young composers who are doing very well, do you encourage them to join ASCAP?

ES: I certainly do. I certainly do. I do it all the time.

BD: What other advice do you have for young composers?

ES: Heh, heh! Be strong! [Laughter] And there’s another, quasi humorous item, but I think there’s a lot to it. When a young composer asks how to get along in this world, I always say, “Get out of town!” because for the young composer, it is always impossible to get anywhere in the place where you are. There’s always groups to play established people, and why should they let anybody else in on it? But if you go to some place that’s a thousand miles away, they say, “Oh! You’re brilliant!” Why? You’re taken much more seriously. I got my first performances out in the Midwest and in the South, and only later did I begin to get performances in New York.

BD: I noticed you've had a number of premieres in Oklahoma. Did they play your music well there?

ES: Yes, yes, they did. There is a very fine conductor named Guy Frasier Harrison and he would always hand me a tape of what he did, and he did a terrific job.

* * * * *

BD: You’ve written quite a number of operas and also a couple of musicals. What really is the difference between a musical and an opera?

ES: Well, a musical is basically entertainment, and I think there are limits to which your music can be written. It can be, shall we say, introspective, or highly charged with a very personal quality. It’s very, very hard to put it in words. Obviously, a musical has to appeal to a very broad public, and a broad public wants to get something that’s extremely tuneful. I’m not against that. A musical can be full of laughs, but I think opera isn’t. There's no basic difference really, except that in opera you may search out different kinds of harmonies and different rhythmic patterns that might be more difficult to sell on Broadway.

BD: In opera, where is the balance between entertainment and art?

ES: Again hard to say. It’s always got to be entertaining, but sometimes, in opera, the entertainment is not as immediate or straightforward. I don’t want to use derogatory terms, but musicals have more obvious characteristics. I think there are certain patterns and perhaps certain clichés of the Broadway stage that are expected always to be there, and, as you know, the finest and smartest composers can use them in a very fresh way. But I think in opera you have more range for a variety of musical forms and a variety of musical textures. However, if some Broadway producer came to me next week with a terrific story and said, “I want you to do a score,” maybe I would do it. [Laughter]

BD: I assume you have many, many commissions. How do you decide which commissions you will accept and which ones you will decline?

ES: Sometimes there are certain qualities or certain subject matter, perhaps, that they want, and it doesn’t interest me. So I say I can’t do it. Other times they may ask me what I want to do, and I will tell them. They may say no and they may say yes. So it’s a process. It’s all the feeling you weigh. It also has much to do with what you’ve been doing recently. I like to keep changing off. I don’t want to do three string quartets in a row or four choral pieces in a row. I find that my mind gets tired and I like to keep it refreshed by switching media, and also switching the moods. If I have been doing chamber music, maybe then I want to do something for the theater or something for the orchestra. I might want to compose songs and so forth.

BD: So in your whole life, then, you need balance and contrast.

ES: I try to keep myself interested. [Laughter] I think that’s the name of the game.

BD: And I assume you try to do that in each individual piece you’re working on.

ES: I hope so.

* * * * *

BD: Let’s come back to your early operas. Tell me about Darling Corie.

ES: Darling Corie was my first opera. It’s a one-acter, rather short, with a rather small cast. It was meant, really, to be something for opera workshops. This goes back to 1951. At that point I wanted to try my hand at an American folk opera, so I took the ballad, with its gray, elemental story of a country girl and the city man, or, as we/he turned out to be running away into so forth, and so was she/he and so forth. Someone had called it the “American Cavalleria Rusticana.” Two men in a plight over this one girl, one tried to kill the other, and so forth. It has a kind of elemental quality of that time.

BD: Would it work well then on a double bill with Cavalleria Rusticana?

ES: Hey! You know, that’s an idea!

BD: Or perhaps, being the same story, would it work well with Pagliacci?

ES: [laughter] Why not? Why, that’s a great idea!

BD: When producing a short work of yours such as this, would it be better to put it on with another contemporary work, or with an established work?

ES: I think with a contemporary work. When one opera is the Mozart Impressario or even Wolf-Ferrari's Secret of Suzanna, I think that’s just too much of a gap. I feel more comfortable with another American work or maybe something of Ravel, the one about the clock maker, L’Heure Espagnole. I wouldn’t mind that.

BD: Or perhaps with another work of yours, or is that too much?

ES: Oh, no, no, never too much! [Laughter] I’ve had double-bills of my work, yes. Darling Corie works very well with Miranda and the Dark Young Man, which is a comedy. It’s tongue-in-cheek and somewhat more sophisticated in its approach, so they balance each other off.

BD: Both are short works?

ES: Yes. Miranda is a little longer. It’s nearly an hour, so it makes a good evening.

BD: Your next one is The Mermaid in Lock no. 7. Tell me about that.

ES: That was an idea that came to me from a man named Robert Boudreau who runs the American Wind Symphony in Pittsburgh, a group of about 60 or 70 wind instruments. He’s been commissioning all kinds of works for that ensemble. In 1957, Pittsburgh was going to celebrate its tri-centennial as a settlement, and he came to me with an idea of doing something that would celebrate the city. He brought this song about a mermaid who falls in love with this American sailor who comes from Pittsburgh. The mermaid actually lives in England off Land's End in the Atlantic Ocean. This American boy is in the navy, and when he gets back home, he falls in love with a tootsie from the local bar. He forgets about the mermaid, but SHE doesn’t forget him; she swims across the Atlantic Ocean and through the Gulf of Mexico and up the Mississippi River, up the Ohio River, and appears in the lock in the dam right outside of Pittsburgh... which is where the opera was first performed, by the way. They, they had a barge right on the river at Parr State Park.

BD: Has it been done since then in other locations?

ES: Yes, yes it has.

BD: So it’s not just an occasional piece.

ES: Oh no. No, it’s been done by black companies, as a matter of fact, and been done by people far away from the Ohio River. As a matter of fact, one of the important performances of it was in Antwerp. They translated it into Flemish and did it there.

BD: This brings up the whole question of language. Should operas be translated?

ES: I think so. I believe in opera in the language of the country. I’m one of those people who think that all opera should be done in English. I’m not against doing Don Giovanni in Italian once in awhile, but I really think that the theatrical experience suffers when the audience doesn’t understand what the people are saying up there. I enjoy very much operas in original language on television with, with sub-titles. Of course now they have super-titles. I haven’t seen too many of them, though.

BD: I was going to ask you if that is the ideal compromise.

ES: It might be. I don’t know; I’d have to see more of them. I wonder about the windmill effect of looking up and down all the time. That might be a problem, but I think anything that brings the stage and the composition close to the audience is something I’m in favor of.

BD: Continuing with your own operas, the next one is Dublin Song which became The Plough and the Stars.

ES: Yes. Well this goes back to about 1960 when I had already written the three one-acters that I thought had gone over very well. I said to myself, “It’s time to bite the bullet and do a full-evening opera." I was looking around at various plays that I could set to music, and many of them I wanted to do I couldn’t get the rights to, and others, for some reason or other, didn’t appeal to me. One time I was actually writing on the sofa in the living room, right next to the room where I’m sitting now, reading a book of plays by Sean O’Casey, and I jumped up with the book in my hand and went into the kitchen where my wife was, and I said, “Gads! I just came across a text for a marvelous opera." She asked what it was and I said it was by Sean O’Casey. She asked if I was going to do it and I said no, because the opera’s so Irish, and my music is supposed to sell better. I didn’t know whether I could do something like that without being Irish. Well, she countered that Puccini had done pretty well with a Japanese subject and a Chinese subject, so I started scratching my head and thinking, “You know, maybe you’ve got a point that I didn’t think of." I subsequently wrote to Sean O’Casey, and he gave me the rights to do it.

BD: Was he pleased that you wanted to set it?

ES: Yes, he was! He was. As a matter of fact, I have a beautiful letter of his that says, “Some day come and visit my studio." It’s hanging up on the wall, and he said that he’s very, very happy that I’m going to do the opera, and he gave me the rights. And then at the end he said, “May God and good fortune come to all our help.” [Laughter] We had several performances here in the states and we got a wonderful performance of it in Bordeaux at the Grande Theatre de Municipal, where they translated it into French. That goes further to answer your question. I was pleased as punch that they were doing it in French.

BD: An Irish opera written by an American being performed in French. It really makes the whole thing much more universal.

ES: Think of William Shakespeare. He wasn’t a Dane or a Roman or an Italian, and he did pretty well with those subjects.

BD: Speaking of Shakespeare, your Night of the Moonspell is an adaptation of his Midsummer Night's Dream.

ES: Yes. It was a commission for the Bi-Centennial a little

more than ten years ago from the Shreveport, Louisiana Symphony. They

wanted me to do an opera and offered me a triple commission. The opera

was to reflect Louisiana, so once again it was a long drink of water.

My collaborator, Edward Mabley, and I read every conceivable play or story

dealing with Louisiana, and it took about a year. We just couldn’t find anything

that was exciting, that seemed interesting. Once again my wife gave

me the idea. She does have good ideas. We were having breakfast

and I said, "I just haven’t found a damned thing. Give the advance

back and tell them it’s not working." She said, “Why don’t you do Shakespeare?”

I said, “Shakespeare? What kind of Shakespeare has to do with Louisiana?”

[Laughter] She said, “Well, you know, Shakespeare transported plays to the

seacoast of Bohemia. He didn’t balk at moving them around." So at that

point, something flashed in my mind and I said, “Gad! ‘Midsummer Night’s

Dream. Midsummer Night’s Dream! Midsummer Night’s Dream!” And in three

seconds flat the thing struck me that Midsummer Night’s Dream is really

three stories pasted together that all intersect. So I thought we could

do this in Louisiana, and I talked with Ted Mabley. He said, "The aristocrats

rip the rich white plantation owners along the banks of Mississippi; the

mechanicals could be the Cajuns and the fairies are the blacks." It

was a brilliant idea! So, once again, as I have done in some other

works, I have taken three levels of three musical genres or accents or whatever

for the three different groups. In other words, the white plantation

owners have kind of a not that complicated, but still more sophisticated contemporary

music style. The Cajuns have a folkish style. I didn’t actually

use any Cajun tunes because I couldn’t find any that seemed to fit the bill.

But I did try to create something of the atmosphere there. And of course

for the blacks you want to use black music. There’s a wonderful passage

in there where the music takes off in which the queen is going to leave the

place once she wakes up, but what she thinks she sees is Bottom, whom you

know as an ass, [laughing] and falls in love with him. So there’s a

duet in the opera of the queen and Bottom. She has a kind of wonderfully

sexy, bizarre aria. It has kind of a beige impression, and since he’s an

ass, he sings schwartzo music. [Laughter] That’s the love duet.

And for the last scene with Pyramis and Thisbe, instead of writing a play

within a play, the Cajun workmen are writing an opera within an opera.

As if they don’t know nothin’ about music, they swipe everything they hear

on the radio. They turn on a classical music station and they take

a little piece, the habanera from Carmen, and the other guy does a

hunk of the Tristan Prelude against it, plus a little Beethoven, and

he winds up counterpointing Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. [Laughter]

That really is FUN. I would love to see that again. Unfortunately

I have that one performance and I’m still struggling like mad trying to get

another performance.

ES: Yes. It was a commission for the Bi-Centennial a little

more than ten years ago from the Shreveport, Louisiana Symphony. They

wanted me to do an opera and offered me a triple commission. The opera

was to reflect Louisiana, so once again it was a long drink of water.

My collaborator, Edward Mabley, and I read every conceivable play or story

dealing with Louisiana, and it took about a year. We just couldn’t find anything

that was exciting, that seemed interesting. Once again my wife gave

me the idea. She does have good ideas. We were having breakfast

and I said, "I just haven’t found a damned thing. Give the advance

back and tell them it’s not working." She said, “Why don’t you do Shakespeare?”

I said, “Shakespeare? What kind of Shakespeare has to do with Louisiana?”

[Laughter] She said, “Well, you know, Shakespeare transported plays to the

seacoast of Bohemia. He didn’t balk at moving them around." So at that

point, something flashed in my mind and I said, “Gad! ‘Midsummer Night’s

Dream. Midsummer Night’s Dream! Midsummer Night’s Dream!” And in three

seconds flat the thing struck me that Midsummer Night’s Dream is really

three stories pasted together that all intersect. So I thought we could

do this in Louisiana, and I talked with Ted Mabley. He said, "The aristocrats

rip the rich white plantation owners along the banks of Mississippi; the

mechanicals could be the Cajuns and the fairies are the blacks." It

was a brilliant idea! So, once again, as I have done in some other

works, I have taken three levels of three musical genres or accents or whatever

for the three different groups. In other words, the white plantation

owners have kind of a not that complicated, but still more sophisticated contemporary

music style. The Cajuns have a folkish style. I didn’t actually

use any Cajun tunes because I couldn’t find any that seemed to fit the bill.

But I did try to create something of the atmosphere there. And of course

for the blacks you want to use black music. There’s a wonderful passage

in there where the music takes off in which the queen is going to leave the

place once she wakes up, but what she thinks she sees is Bottom, whom you

know as an ass, [laughing] and falls in love with him. So there’s a

duet in the opera of the queen and Bottom. She has a kind of wonderfully

sexy, bizarre aria. It has kind of a beige impression, and since he’s an

ass, he sings schwartzo music. [Laughter] That’s the love duet.

And for the last scene with Pyramis and Thisbe, instead of writing a play

within a play, the Cajun workmen are writing an opera within an opera.

As if they don’t know nothin’ about music, they swipe everything they hear

on the radio. They turn on a classical music station and they take

a little piece, the habanera from Carmen, and the other guy does a

hunk of the Tristan Prelude against it, plus a little Beethoven, and

he winds up counterpointing Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. [Laughter]

That really is FUN. I would love to see that again. Unfortunately

I have that one performance and I’m still struggling like mad trying to get

another performance.

BD: You have another one entitled Marquesa of O.

ES: That one has not yet been performed. It was suggested to me by a movie I saw directed by the French director Eric Rohmer of this famous old German story by Heinrich von Kleist. To me, it's a real blockbuster. It’s got a combination of whodunnit and a sexy story and war and peace and battles. I really think it’s a humdinger. So far it hasn’t come to the stage, and one of the incentives in hanging on in this world is there’s still something of mine which hasn’t been performed. [Laughter]

BD: Sometimes you write things without any hope of being performed, and once you get them done you look for performances?

ES: Absolutely. Absolutely. You know what you want, and you hope for that. The reason I had the courage to do that, because it took about two or three years to write the piece without any hope of performance, was that at the age of 69 I finally got the Guggenheim award. After having applied for them for how many times, I guess they had to get rid of me in some way, so they gave it to me. [Laughter] So I figured here’s something I never would have gotten and I’d never expected to get it, so it’s a gift from the gods and I should do something that is going to lose money but that I really wanted to do. So there that, that’s how the Marquesa of O came about. But once again, Norman Rosten, the poet, and I transposed the scene from Northern Italy in the Napoleonic Wars to our Southwestern frontier during the Mexican war.

* * * * *

BD: What is next on your calendar?

ES: Well I have a commission to write a choral work for the Brevard Festival in North Carolina where I was composer-in-residence a few years ago. They want me to write a work, and I’m in the middle of that. Then I have to write a fifth piano sonata. My son-in-law, Alan Mandel, has played the first four and tells me that next year he wants to do a concert in New York of my piano sonatas, but the first four don’t add up to quite a whole evening of music, and would I write a fifth? So I can’t say, “No.”

BD: Do single composer evenings work well?

BD: Do single composer evenings work well?

ES: Depends on the composer. I’ve never listened to a whole evening of Buxtehude but I’ve been to a many Beethoven concerts and I like it on a personal level. I had quite a few concerts of my music, and apparently the audience and I have been quite pleased with the result. You have to get a wide diversity. I think composers who tend to write everything in the same manner would get boring. I’m not so sure about Hindemith, for example, but I think there are quite a few composers who could stand a whole evening.

BD: I assume that you expect your music to last.

ES: [Laughter] I would hope so. Some of it has lasted quite awhile already - forty or fifty years that it doesn’t seem to have lost its interest. Well, let me be honest, the answer is “Yes.” I really have to say “I hope so," or, "Maybe." Who knows, but the answer is yes.

BD: Is the art of composing fun for you?

ES: Fun? That’s very difficult to say. It’s a lot of work, and sometimes it’s very painful. Sometimes you get into periods where you say, “Oh! This is ghastly! I’m never going to write another note." I don’t know what's coming next. I get into the deepest blue funk and once again my wife always says that that’s when the thing starts to go well. Look, I’ve been doing it since I was seventeen; if asked about re-living my life, I would have done the same thing. There, that’s it. Oh, you go to all kinds of places and frustrations and everything to make it, but basically when you feel that you’ve written a number of things that you’re not ashamed of and that people seem to enjoy and are meaningful and you’ve spoken up for the things that you believe in, like I’ve done in a number of my works..... One of those things came around about two weeks ago when my song cycle, The Face of War, which I wrote about twenty years ago as a protest against the Viet Nam war, was put on the Rockefeller Competition here in New York. So my publisher called up and said, “Why didn’t you send us a definitive copy? We’re going to publish it." I didn’t think they'd ever publish something as grim, and bloody, and violent as that, but I always felt that it was a good piece. So it sat around for twenty years and now people are doing it.

BD: Now the time is right for it, perhaps.

ES: Perhaps, yeah. I think the time was right for it then, but it took a little more time. I think on that score that I’ve commented and expressed my feelings about the way the world is being run. I have, as you may know, I Have A Dream, a cantata after Martin Luther King. And The Plough and the Stars is really a cry out for justice and humanity.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of the world?

ES: I think it’s going to come to its senses one of these days. There’s the recent shenanigans that have been going on, which will probably have a good result.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

ES: Yes. I don’t know if the styles that are being pushed today are gonna be the ones or something else, but, I think that good composers will continue to appear, who have the courage and the audacity to go ahead and do their own thing and not kowtow to the big forces up on top. That’s why Charles Ives had a very tough time of it as far as music was concerned, and then it happens! Forty or fifty years ago, Henry Cowell and Nicolas Slonimsky and John Kirkpatrick and a number of us young composers who were in there started beating the drum, and finally it caught on.

BD: Right. Exactly. I’m glad you mentioned Slonimsky. He’s a fascinating character.

ES: Oh! He’s my idol. My music doesn’t necessarily follow, except in a certain way, but I think he’s the Walt Whitman of American music. No question about it. We used to be very proud of him. He had the guts to do it, and the imagination.

BD: I'm happy to say he's also been part of my series of radio interviews.

ES: That's very good.

BD: Thank you so much for speaking with me today. You were very gracious to accept my invitation so quickly.

ES: Well any, any friend of Bud Bazelon is a friend of mine.

=== === === === ===

----- ----- -----

=== === === === ===

|

http://artists-in-residence.com/ljlehrman/ElieSiegmeisterSociety.html The Elie Siegmeister Society 10 Nob Hill Gate, Roslyn, NY 11576 e-mail: ljlehrman@gmail.com |

| Elie Siegmeister (b. January 15, 1909, New York City – March 10,

1991, Manhasset, New York) was an American composer, educator and author.

His varied musical output showed his concern with the development of an authentic American musical vocabulary. Jazz, blues and folk melodies and rhythms are frequent themes in his many song cycles, his nine operas, his eight symphonies, and his many choral, chamber, and solo works. His 37 orchestral works have been performed by leading orchestras throughout the world under such conductors as Arturo Toscanini, Leopold Stokowski, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Lorin Maazel, and Sergiu Comissiona. He also composed for Hollywood (notably, the film score of "They Came to Cordura," starring Gary Cooper and Rita Hayworth, 1959) and Broadway ("Sing Out, Sweet Land," 1944, book by Walter Kerr). Siegmeister wrote a number of important books on music, among them "Treasury of American Song" (Knopf, 1940-43, text coauthored with Olin Downs, music arranged by Siegmeister), second edition revised and enlarged (Consolidated Music Publishers); "The Music Lover's Handbook" (William Morrow, 1943; Book-of-the-Month Club selection), revised and expanded as "The New Music Lover's Handbook" (1973); and the two-volume "Harmony and Melody" (Wadsworth, 1985), which was widely adopted by college and conservatory curricula. From 1977 until his death, he served on the Board of Directors of ASCAP and chaired its Symphony and Concert Committee. Among his signal achievements, he was composer-in-residence at Hofstra University 1966-76, having organized and conducted the Hofstra Symphony Orchestra; established 1971 and chaired the Council of Creative Artists, Libraries, and Museums; and initiated 1978 the Kennedy Center's National Black Music competition. In 1939, he organized the American Ballad Singers, pioneers in the folk music renaissance whom he conducted for eight years in performances throughout the United States. He was the winner of numerous awards and commissions, among them those of the Guggenheim, Ford, and Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundations, the Library of Congress, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the USIA. Siegmeister earned a B.A. cum laude at the age of 18 from Columbia

University, where he had studied music theory with Seth Bingham. He studied

conducting with Albert Stoessel at the Juilliard School and counterpoint

with Wallingford Riegger. He was among the numerous American composers, including

Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, and Mark Blitzstein, who were students of

the influential teacher Nadia Boulanger in Paris. The best known of his own

students was Stephen

Albert (1941-92), winner of a 1985 Pulitzer Prize for music. Other students

included clarinetist Naomi Drucker and composers Michael Jeffrey Shapiro,

Daniel Dorff, and Leonard Lehrman. |

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded on the telephone on March 7, 1987. Portions

were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1989, 1994 and 1999. An

audio copy of the conversation was placed in the Archive of Contemporary

Music at Northwestern University. This transcription was

made in 2007 and posted on this website in March of 2008.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other

interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with

comments, questions and suggestions.