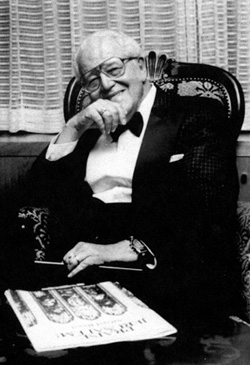

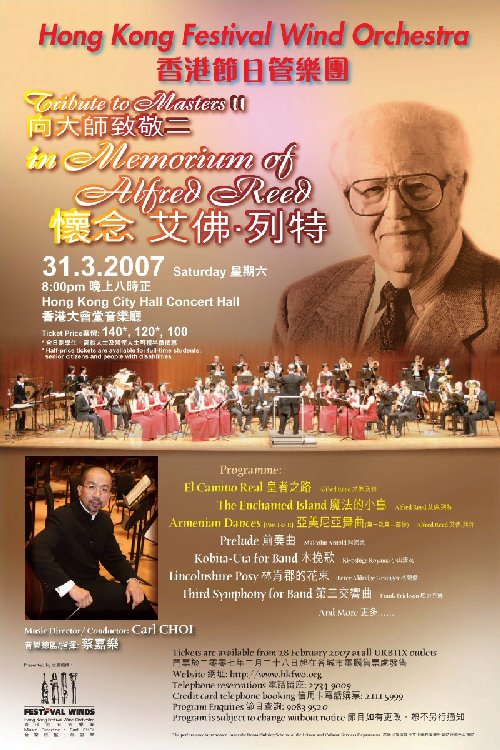

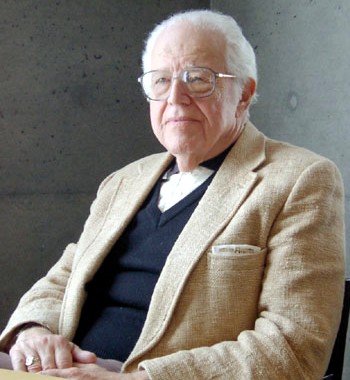

| Alfred Reed

(January 25, 1921 – September 17, 2005) was one of America's most prolific

and frequently performed composers, with more than two hundred published

works for concert band, wind ensemble, orchestra, chorus, and chamber ensemble

to his name. He also traveled extensively as a guest conductor, performing

in North America, Latin America, Europe and Asia. He was born in New York and began his formal music training at the age of ten. During World War II he served in the 529th Army Air Force Band. Following his military service he attended the Juilliard School of Music, studying under Vittorio Giannini, after which he was staff composer and arranger first for NBC, then for ABC. In 1953 he became the conductor of the Baylor Symphony Orchestra at Baylor University, where he received his B.M. in 1955 and his M.M. in 1956. His master's thesis "Rhapsody for Viola and Orchestra" was awarded the Luria Prize in 1959. He was a member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, the national fraternity for men in music. From 1955 to 1966 he was the executive editor of Hansen Publications, a music publisher. He was professor of music at the University of Miami (where he worked with composer and arranger Robert Longfield) from 1966 to 1993 and was chairman of the department of Music Media and Industry and director of the Music Industry Program at the time of his retirement. He established the very first college-level music business curriculum at the University of Miami in 1966, which led other colleges and universities to follow suit. Some of his more memorable quotes while teaching music business courses are: "You can't give away what you are trying to sell and expect to stay in business" and "I am the second most published composer next to J.S. Bach" At the time of his death, he had composition commissions that would have taken him to the age of 115. Reed was a member of the Beta Tau Chapter of the National Men's Music Fraternity, Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia. Many of Reed's wind band compositions have been released as CD recordings by the Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra. |

For many years, Alfred Reed attended the Midwest Band and Orchestra Clinic

which is held in Chicago each December. There, young musicians and

ensembles gather to learn, share, explore and experience the technical and

communal aspects of music in general and their particular instruments.

Guests from around the world arrive and publishers have booths which

are always bustling with business. Eager young men and women swarm

around all the displays while managing to be at their appointed seminars

and performances. It's always a great four days, and for many, it's

a singular thrill to be here in the Windy City.

Prior to the 1986 gathering, I asked this distinguished composer and conductor

if he would be willing to take a bit of time from his hectic schedule to

sit down with me for a chat which would be used on WNIB. Since I had

a regular program series called This Month's

Band Concert, he agreed, and we met in his hotel room. He was

friendly and gregarious, and enjoyed speaking about our favorite topics.

Though we were interrupted a couple of times by the telephone, he always

came back to the topic of the moment and seemed very pleased with the directions

our conversation took.

Here is what was said that afternoon . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You are composer, conductor and teacher.

Let's start with the instructional side. How has the teaching of young

musicians changed over 20, 30, 40 years?

Alfred Reed: That's a very interesting question. I am a firm believer in the fact that during the past 20, 30, 40 years we have been building up to a veritable revolution in - and I use the word advisedly - "culture." As a matter of fact, since 1980, we have been living in a technological revolution unmatched in history since Gutenberg cranked up the first printing press 500 years ago, and the world could no longer be the same.

BD: Is this a good revolution, a bad revolution, or both?

AR: I think the jury is

still out on that. In some respects, you could argue it's the greatest

and best of all revolutions, and in some respects you could say, "Well, we

don't know what's going to happen." It's like a volcano that throws

up a lot of mud and rocks along with pure molten lava. You don't know

about this until it's all over, and this may never be over. The revolution

is in communications technology. It's now possible for us to reach

every single person on the face of the earth, no matter where they live,

even if they live at the North Pole or in the Amazonian jungle, as long as

they have a screen, two speakers, a dish, and access to electric current.

And since music is the greatest of all the communicative arts - at least

I believe it is - this literally means that no matter where one lives, we

can be in all the great places of culture - for instance, Orchestra Hall

in Chicago. I had an absolutely super-dramatic experience of this just

last year when I was asked to conduct at one of the districts of the Pennsylvania

Music Educators Association. This was in a little town near the Pennsylvania-Ohio

border that was so far west in Pennsylvania you had to fly to Youngstown

in Ohio, where they picked you up in a car then drove you back east across

the border. It is a fairly nice city undergoing hard times because

it's part of the steel dynasty, so to speak, but the point is that I was

there and I was snowed in to that town. When I got there they had about

four inches of snow on the ground, and there was a blizzard on the way in

which finally struck, and I was absolutely immured in my motel room.

It was the end of a long day of rehearsing, and I decided to have a shower

and stretch out before going to dinner. So I just flipped on the TV

set to see the news, and there I was in the middle of the Metropolitan Opera

House in New York, watching and listening to a performance of Zandonai's Francesca da Rimini. Now that work

had not been given at the Met for 62 years! It had just been brought

back in a super production under James Levine, with a sterling cast, and

the costs of re-mounting this work - I believe in the second act there's

a battle between two opposing armies on the stage - was such that the tickets

had to sell for 100 dollars apiece! And here I was in this small town

on the Pennsylvania-Ohio border, buried in a blizzard, no place to go, and

I was attending the opera, seeing and hearing it as I couldn't see and hear

it even if I had one of those 100-dollar seats! And if I had had a

VCR and eight dollars worth of blank tape, I could've had that performance

forever.

BD: Does it please you that

you could call someone now and buy a tape of that performance?

AR: It most certainly does please me because as a composer, my biggest problem is not how to master the sonata form. If I'm any kind of a composer at all, that's taken as a matter of course! I mean, if you're going to be a quarterback like Dan Marino, or a Wilbur Marshall on the Chicago Bears, you don't really teach anybody how to throw a ball or block it. That's taken as a matter of course. And, as with all composers, the larger my audience the better I am pleased! But I guess I'm old enough to consider that something like this is nothing short of a miracle!

BD: Then let me ask an impossible question. What do you do with your music?

AR: What one does with one's music today is to realize that whereas

when my father was born 100 years ago, there were only two ways of listening

to music - you either did it yourself, played, sang yourself, or you went

somewhere where someone was playing or singing, and sat down to listen!

And now, talk about a revolution! Today these are the least of the

ways in which anyone, including musicians, comes into contact with live music!

Now that's a 180-degree turnaround in less, really, than 100 years.

To me that's a revolution. That's change, and violent change.

AR: What one does with one's music today is to realize that whereas

when my father was born 100 years ago, there were only two ways of listening

to music - you either did it yourself, played, sang yourself, or you went

somewhere where someone was playing or singing, and sat down to listen!

And now, talk about a revolution! Today these are the least of the

ways in which anyone, including musicians, comes into contact with live music!

Now that's a 180-degree turnaround in less, really, than 100 years.

To me that's a revolution. That's change, and violent change.

BD: Are there still enough people that are performing music, doing Hausmusik, as it were?

AR: That, of course, is the 64 million-, or billion-dollar question. About 120 years ago, a man who presumably knew something about music named Richard Wagner, made a statement which has come down through the years. He said, "The spirit of music as an art is not kept alive in our professional theaters and concert halls, but on the cottage piano of the dedicated amateur." And I think that is still completely true.

BD: So it's not kept alive, then, on a flat piece of plastic?

AR: In a sense, the flat piece of plastic is really, today, an instrument. In the Music Industry Program that I am responsible for at the University of Miami, this is one of the most controversial areas that we go into. I try to show the students that 100 years ago, if an ordinary human being - not a musician at all, but an ordinary music lover - had become infatuated with the solo violin sonatas of Bach, works which any musician would place at the very top of our achievement, how could he hear those works? Either he had to go somewhere where Joachim or Ysaÿe or any of the great violinists of that time was playing and might've included one of them on his program, or he had the option of learning to play the violin himself!

BD: Get yer fiddle outta the case and start sawin' away. [Laughs]

AR: [Chuckles, then speaks with a tone of voice expressing awe at the greatness of these works] Well, in the case of the Bach solo violin sonatas or suites, ten to fifteen years is just the beginning of your preparation to play such works. But those were my only choices! Today I can take either a Sony Walkman and plug it into my ears or put a tape on my hi-fi rig and press a button, and there is the music. This may sound startling to some people - in fact, quite frankly, I hope it does - my contention is that the musical reproducing instruments, by which I include all the magic stereo CD hi-fi hardware, is a musical instrument in itself, and the reason for that is that the latest statistics for the Japanese tape manufacturers show that in 1984 they shipped over 900 million units of blank tape to this country, not for the record companies or the commercial users, but for people like you and I.

BD: The individuals.

AR: Individuals only.

And that the best educated guess by RIAA, the Record Industry Associates

of America which is the official watchdog agency for recorded music, something

like 98.8 percent of all that blank tape was used to record just one thing:

music! Not sermons, not speeches, not . . .

BD: [Interrupting] Not interviews

like this one??? [Laughs]

AR: [Also laughs] Nope,

just music. This poses a very interesting question. After all,

what is the violin? It's made of 32 different pieces of wood, glue,

varnish, plastic, metal for the strings, catgut in the older days, and its

function is to bring music alive, to make sounds in the air! I mean,

nobody really buys a violin for decoration, except maybe a few interior decorators.

But if that's true, then what is the tape deck and the piece of plastic that

you refer to? It is nothing but an instrument designed to bring music

alive.

BD: Then let's take this

one step further. If the sound-reproducing equipment is an instrument,

then do the consumers have to learn to play that instrument the way a violinist

needs to play his instrument?

AR: I am delighted you asked

that. Here is the question that I pose to my students, and hopefully

to your listeners everywhere. You have two choices: fifteen years of

practicing to be able to play it halfway decently if you're lucky, or five

minutes' reading of the instructions that came with the Walkman. The

end result is the same: you are hearing Bach alive, which is presumably

what it's all about!

BD: So, then, are recordings

really live performances?

AR: That's another very

good question. How do you tell the average listener that the performances

that he hears today never really existed? They are exactly like Dr.

Frankenstein's monster's body. They have been pieced together from

various performances to the point where today we can enjoy something that

heretofore we only dreamed about - technically, sonically perfect renditions.

BD: Are they too perfect?

AR: That's a good question!

That's an excellent question. I hold another revolutionary belief that

one of the real thrills in attending a live concert is to see whether or

not it's going to go really well at all. Whether the horns are gonna

make the high E-flat in Don Juan,

whether the strings are going to be able to manage those impossible passages

in Wagner and Strauss. That's part of the thrill! You don't know!

But you do know one thing, that when you're sitting in Orchestra Hall or

at any other concert, it's happening there in front of you, and you are a

part of what I call the real re-creation of the music inside the listener!

Whereas with a tape, it is like hearing it through a curtain, or seeing it

through a mirror. Now the mirror may be absolutely perfect, it doesn't

distort, but it's not the same thing as seeing the person face to face.

BD: You're seeing the reflection instead?

AR: Exactly! If I were to turn my back on you and look into a mirror, I would presumably see you! But that's not quite the same thing, is it, as seeing you face to face? And that is a question that each music listener has to decide for himself or herself.

BD: Then does this sonic revolution create false expectations when those same people go into the concert hall?

AR: Absolutely. Here I can speak definitely as a person closely associated with music education. The people who are in charge of Music Ed., teaching the kids in the grade schools in those early, crucial years from about 5 to 12, say that when these kids do go into a concert hall, after having been brought up on the tape-recorded miracles, complain because it never sounds in the concert hall the way they hear it with those little Sony Walkman speakers, because that's what they are, deeply implanted in the inner recesses of the ear! And that raises another very important issue. If we say, "But you shouldn't enjoy it that way. You should enjoy it live, because that's the way it's been up to our time," the kids say, "Well, isn't that just too bad, pops? You and Mom had your chance. Now we like it this way, and who are you to tell us that we're not to like it that way?"BD: Should they not both

be able to exist?

AR: That is the ideal.

I believe that music education no longer has any justifiable reason to exist

if all it's going to do is to teach Tommy or Sue how to play a little melody

on the flutophone, and hopefully they'll then take up saxophone! I

say that music education is designed to teach professional audiences.

And what in the world is a professional audience? It's an audience

that has come to exactly the point that you just raised. They realize

the beauty of having the music where you want, when you want it, how you

want it; of hearing sonically perfect performances but will not give up the

thrill of being there, in the flesh, when the music is literally re-creating

itself inside you, live. And that's as far, I think, as we can take

it.

* *

* * *

BD: Now we've talked about the technological revolution, so let's talk a little bit about the music itself. How has music changed in your lifetime as you've watched and listened?

AR: I think we are in the

same position today with music as we have been with, let's say, drama and

singing. [chuckles] Not that singing isn't music, but the kind of performance

that it gives. In years gone by, an actor, whether he was a Shakespearean

tragedian or an out-and-out slapstick burlesque comedian, could use the same

act for 20 years, He could go around performing in front of live audiences

in hundreds and hundreds of theaters, and never have to change! Today

you can't do that! You go on one show - you get the press agent's dream

of an appearance on the Johnny Carson Show, and millions of people see and

hear you. Then if you keep on doing the same thing too many times after

that, you're not gonna get called again. We are able to expose music

and artists to a far greater audience in a miniscule time, today, than ever

before in history and it wreaks changes in every area of the profession -

in management, in programming, in recording. No conductor today can

literally afford to stay with one orchestra anymore. They have to be

all over the world. The same thing with the opera singers. Two

years ago there was a major article dealing with the fact that all the orchestras

around the world are all beginning to get the same kind of homogenized sound!

In my time, the Boston Symphony, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the New York

Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony each had their own qualities. You

could pick it up like that and it was because the conductors stayed with

them. But today, when each conductor conducts every single orchestra

and comes in with his or her own particular ideas, there tends towards a

sort of a homogenization. Some people say that that's for the better,

the same way as the Football Draft where the idea is to achieve parity between

all the teams so that not just three or four teams constantly win all the

time. There's more excitement, more of a real contest. That may

very well be true, but in the arts, we know that you achieve parity at the

cost of leveling off the peaks. Sure, you raise the bottom, too, and

this again becomes a personal judgment, but do you want to cut down the peaks

in order to raise the bottom and end up somewhere here instead of every now

and then having a Beethoven or a Wagner or a Strauss or a Hindemith, and suddenly

the world is turned topsy-turvy again?

BD: All this is about performing. Does the same kind of thing hold true for composing?

AR: Worse than ever. Today, a young man in this country who wants to be a composer faces an absolute plethora, a tidal wave of styles. He hears everything and he hardly knows how to make a decision as to where he fits in with all this.

BD: So where is music going today?

AR: That's a good question.

I have the statistics to prove it, but overall, there is more music being

made and performed and purchased and listened to, today, than ever before

in the history of the world. In this country that has been at the expense

of a really national style. We don't have that in this country, and

it is very possible that we never will, because, artistically as well as

ethnically, it seems to me that we're a big, big stew. Now stew can

be a wonderful meal! My wife prepares a stew and I enjoy it!

But stew is stew! It's not filet mignon, or it's not pâté

de foie gras, or breast of turkey prepared this-and-this style. But

it's good! And it's healthy. And it's a whole meal in itself.

And we have so many different kinds of rock. And in the serious field,

my God, who would dare to try to make a catalog of all the different styles

that we have today? I don't think anyone could. It's impossible!

Now that's to the good because it gives everybody a chance. Every young

and not so young composer has the chance to bring their product, if I may

use such a commercial term, to the marketplace, and see who buys, and who

doesn't buy. But as far as an American style is concerned, the last

time I think we could've said this was in the middle '30s and '40s, when I

was growing up, when Roy Harris, William Schuman, and Aaron Copland were the

American style.

BD: Are we then approaching

a global style rather than a national style?

AR: Yes, I would say so, at least within my experience.

I have conducted in several foreign countries, especially with wind groups.

I've conducted in England, France, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands,

Austria and Switzerland. I was even in Czechoslovakia the year before

the uprising. I conducted 25 minutes of Porgy and Bess, and that concert was

sold out two months before we even reached Prague. The audience there

at that time made that particular performance. I'll never forget this

as long as I live; it was the occasion for such an outburst of pro-American

feelings. I tell you, it could bring you to the verge of tears.

To them, that was our American music, and that music spoke to them.

Later I learned of how strong the feeling is among Ukrainians, in the Soviet

Union, for Dolly Parton and her music. And, you know, it took me a

while to accept this, but it occurred to me that if you listen to the lyrics

of most country and western music, it doesn't describe a particularly happy

style of life. Most of those lyrics deal with adultery, with booze,

with divorce, with betrayal, and that evidently strikes a chord in the kind

of lifestyle that Georgians in the Soviet Union enjoy! Her records,

which are on the black market, sell more than any others, at least in recent

years. So it is very possible that our music, or our musics, appeal

strongly around the world far more so than they used to. It used to

be that German music conquered the world! I'm a first-generation American.

My parents were Austrian, Viennese, that came to this country before the

First World War, and in our house there were the Four Bs: Beethoven,

Brahms, Bach, Bruckner, and Wagner. And these men, in my family, were

not musicians! These men, in my family, were heroes. They were

far above the Kaiser, the generals, the politicians, and that's the way it

was. But this country, I think, is finally coming out of its adolescent

stage, but like an adolescent, it sometimes still dirties its underwear,

and that's okay. You just get a good soap and it cleans it off.

We're like a volcano, we're throwing up everything, and anybody with any

kind of a style has a chance to be heard.

AR: Yes, I would say so, at least within my experience.

I have conducted in several foreign countries, especially with wind groups.

I've conducted in England, France, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands,

Austria and Switzerland. I was even in Czechoslovakia the year before

the uprising. I conducted 25 minutes of Porgy and Bess, and that concert was

sold out two months before we even reached Prague. The audience there

at that time made that particular performance. I'll never forget this

as long as I live; it was the occasion for such an outburst of pro-American

feelings. I tell you, it could bring you to the verge of tears.

To them, that was our American music, and that music spoke to them.

Later I learned of how strong the feeling is among Ukrainians, in the Soviet

Union, for Dolly Parton and her music. And, you know, it took me a

while to accept this, but it occurred to me that if you listen to the lyrics

of most country and western music, it doesn't describe a particularly happy

style of life. Most of those lyrics deal with adultery, with booze,

with divorce, with betrayal, and that evidently strikes a chord in the kind

of lifestyle that Georgians in the Soviet Union enjoy! Her records,

which are on the black market, sell more than any others, at least in recent

years. So it is very possible that our music, or our musics, appeal

strongly around the world far more so than they used to. It used to

be that German music conquered the world! I'm a first-generation American.

My parents were Austrian, Viennese, that came to this country before the

First World War, and in our house there were the Four Bs: Beethoven,

Brahms, Bach, Bruckner, and Wagner. And these men, in my family, were

not musicians! These men, in my family, were heroes. They were

far above the Kaiser, the generals, the politicians, and that's the way it

was. But this country, I think, is finally coming out of its adolescent

stage, but like an adolescent, it sometimes still dirties its underwear,

and that's okay. You just get a good soap and it cleans it off.

We're like a volcano, we're throwing up everything, and anybody with any

kind of a style has a chance to be heard.

BD: Should the concert artists

try to entice the rock audience into their concert halls?

AR: I think that any artist

should entice as much of the audience into the concert hall as he can because

the old distinctions that used to be so cast-iron are falling away.

I remember when I was a student, the parameters dictated that this far we

go and no further in the forms, in the structures, in the rhythms, in the

harmonies, in the melodies. The Richter book on harmony says "This

is as far as you go!" [Richter, E. F. (Ernst Friedrich), 1808-1879.

Richter's Manual of harmony: a practical guide to its study: expressly prepared

for the Conservatory of music at Leipsic by Ernst Friedrich Richter.

Tr. from the 8th German ed. by J. C. D. Parker. Boston, O. Ditson & company,

1873.]

BD: [Chuckles]

AR: If you wanna write, there's where you can write. I think this has all been swept away, and nowhere has this happened more strongly than in the wind orchestra field. While we have only so many symphony orchestras, we number the wind groups in the tens of thousands. After all, that is why I'm here in Chicago this week, as I have been for the past 31 years, attending this clinic. And since the majority of the performers in these wind groups are in their most impressionable years, here is where the bulk of your educated audiences are coming from. That is one reason why I as a composer deliberately chose to associate myself with this field! Because without audiences it doesn't matter whether it's the six Bs: Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Berlin, Bacharach, and the Beatles! It isn't gonna work if there's nobody out there in the audience! And if there's nobody out there in the audience, there's nobody that's going to buy the tapes and the records! I think it is very instructive to note that none of the record companies that deal with pop and rock and soul will sign an artist to a recording contract unless that artist also agrees to go out and do a certain number of live concerts every year, on a continuing basis. They do not believe, in other words, that even an Elton John, as an example, can exist solely in the form of records. And I believe that, too, that without the live audience, I don't care what the length of the music's hair is, or the depth of its philosophy, it cannot survive.

BD: Then let me ask a philosophical question. In music, where is the balance between art and entertainment?

AR: An excellent question, and one that has been debated. I think it's all in how you define entertainment, Bruce. If you define "entertainment" in the serious sense as something that reaches out, grasps your attention, holds it, and makes you turn the next page in the book you're reading, or keep on listening as the music unfolds itself, then that is almost a precondition to art. According to this definition, which I believe, art is the substance of the whole experience after you've read through all the pages in the book, and after you've heard all the notes in their proper relationship to each other in the course of a piece of music. There's the difference between the performing arts and the visual arts. You walk into a room and you see the picture all at once. It's there, and what's more, you know that if you walk out of the room and close the doors, the picture will still be hanging on that wall... unless you believe in the fifth and sixth dimension, and I don't want to get into that kind of metaphysical discussion. But presumably, in ordinary experience, the picture is there, the piece of statuary is there! Not so with the music. Whether it's a live performance or you turn off the tape deck, it's gone! It has to be recreated. But you can't recreate a 50-minute work all at once. There's an old parlor trick that I do sometimes when I'm asked to talk to student groups, or chamber of commerce luncheons, and that is [in a declarative voice] "I'm now going to play the entire Beethoven Fifth Symphony at once, the equivalent of walking into a room and seeing the picture or the photograph staring you in the face on the wall." And everybody wonders what I'm about to do! I simply go over to the piano and I bring down both of my arms and hands, and hit as many keys as possible. And I say, "There it is all at once!"

BD: "Now you have to sort it out." [Chuckles]

AR: Yeah. But, you

see, that's what the composer is doing! He is bringing order out of

what otherwise would be tonal chaos! You listen to music, incidentally,

the same way that you program a computer - bit by bit! The computer

can't take it all in at once; it's got to do it one bit at a time!

And then as you do this, the whole totality of the music's design suddenly

makes itself felt within you. And that is the artistic experience.

BD: In a computer, though, each bit is an individual bit. When you're listening to music, are they not often collective bits, like a brass chord or a string section?

AR: We do this with a computer, too. You set up a string! On a computer you input in a whole sentence of, say, six words denoted by one letter or symbol, and when you press that one letter, the computer responds to the whole thing! So that's the equivalent of the vertical chords .and blocks of sound that we get. I'm sure I'm going to offend some of your listeners by saying it, but this is why, at bottom, the artistic experience has to be an intellectual experience because only the mind is capable of remembering the notes that we no longer hear. If you know the work of anticipating the notes that are to come, and are literally building the design of the piece within itself, when that happens - when the notes themselves can cause the listening mind, through the ears, to do this - there, I think, you have that specific type of communication which I would call "art." Entertainment by itself is not enough. After all, if entertainment is only going to be grasping and holding your attention, I can do that with a triple-X porno film or magazine. Baby, that'll hold your attention!

BD: [Chuckles]

AR: But that doesn't leave

that residual design, that when it's all over you're saying, "My God, wasn't

that something! We've got to do this again." That's what keeps

all of us, if I may put it crassly, in business! [Laughter]

* *

* * *

BD: Are you the ideal conductor of your works?

AR: No, not necessarily. I have learned something that

other conductors who were composers first had to learn and you will find

the same thing in Stravinsky's letters and in passages in his autobiographical

comments which Mr. Craft collated into his books, because Stravinsky, Brahms,

and several others had to go and take lessons in how to conduct their works.

I did not become a conductor until fairly late in life, and only because I

received invitations to come out and conduct my own music. Obviously

you don't wish to stand on the podium and make an utter jackass of yourself,

not even with a high school band! You have to know what you're doing!

Even though I wrote the work I still had to learn how to conduct it.

It is not the same thing! It may be heads and tails of the same coin,

but the head is not the tail, and vice versa. So I had to learn how

to do this to the point where at least I could produce results, usually within

limited time. So conducting was, for me, something that I had to learn

how to do, very much as a performer simply has to learn and keep in practice

on his instrument or her voice.

AR: No, not necessarily. I have learned something that

other conductors who were composers first had to learn and you will find

the same thing in Stravinsky's letters and in passages in his autobiographical

comments which Mr. Craft collated into his books, because Stravinsky, Brahms,

and several others had to go and take lessons in how to conduct their works.

I did not become a conductor until fairly late in life, and only because I

received invitations to come out and conduct my own music. Obviously

you don't wish to stand on the podium and make an utter jackass of yourself,

not even with a high school band! You have to know what you're doing!

Even though I wrote the work I still had to learn how to conduct it.

It is not the same thing! It may be heads and tails of the same coin,

but the head is not the tail, and vice versa. So I had to learn how

to do this to the point where at least I could produce results, usually within

limited time. So conducting was, for me, something that I had to learn

how to do, very much as a performer simply has to learn and keep in practice

on his instrument or her voice.

BD: When other people conduct your music, do they find things in it that you didn't know you had put there?

AR: There are times they

find a couple of things that not only didn't I know I'd put there, but I

wish I hadn't! [Laughter] But I hope I've mellowed as I've added

on a few years to the total score (no pun intended) that if I claim the right

to write what I please, when I please, how I please, I have to extend to

the conductor the right to interpret it, obviously within reasonable parameters.

You're not gonna play a funeral march allegro giocoso, but within reasonable

parameters the conductor should feel free to conduct it as he sees the music.

And it is quite true that many times conductors will see things in a composer's

work, or at least give a performance of the work that is actually better

than what the composer himself can do! The greatest example of this

was Tchaikovsky. The last three Tchaikovsky symphonies, numbers 4,

5, and 6, were all conducted by him, and it is a historical fact that these

symphonies did not begin to find any kind of popular acceptance until they

got out of Tchaikovsky's hands, and into the hands of professional conductors.

This is history, not just my interpretation or my feeling. Tchaikovsky

was much too introverted a conductor. According to the eyewitness testimony

that we have, he could not empathize with the orchestral musicians, and the

orchestral musicians, or the wind orchestra musicians, first and foremost,

have got a job to do that is largely technical. You can't stand up

in front of them and discuss art and aesthetics and theories. You gotta

say, "That A is a little sharp, so please bring it down. And not quite

so loud, second flute, because otherwise we're never going to hear the oboe!"

You gotta be practical, and you [snaps fingers] gotta make split-second decisions

be able to respond immediately! The podium is no place for a person

that's introverted. It's impossible for anyone who has difficulty in

expressing his or her ideas! That is why a certain amount - and notice,

please, that I say "a certain amount" - of aggressiveness is an absolute

sine qua non, an absolute requisite

for conducting anything!

BD: But it shouldn't be dictatorial.

AR: Well, I don't think you can quite get away with the dictatorial anymore. The times have changed. Musicians can respect a conductor and they know very, very quickly whether the man or woman up there knows what he or she is talking about, and they respond accordingly! And I think that that is also for the better.

BD: Are you basically pleased

with the recordings that you have made of your works?

AR: Yes. Today, anybody can make a record and do some

pretty good work in this area and produce a sonically respectable product.

So if you are writing music which is performed not just by professional groups,

such as the Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra, or near-professional groups, such

as the finest ensembles in our conservatories and colleges, but with thousands

of high school bands and community groups, you realize that if you're willing

to give the conductor a certain amount of leeway, as I am, then you've gotta

be prepared to put up with what appears. I certainly wouldn't say I'm

ecstatically pleased with everything that I have heard, but, on the other

hand, I have heard some performances that have such fire and spirit in them

when played by what I would call nonprofessional musicians, that in many

respects I would have to give that recording the nod over a sonically perfect,

technically absolutely polished interpretation by one of the professional

groups.

AR: Yes. Today, anybody can make a record and do some

pretty good work in this area and produce a sonically respectable product.

So if you are writing music which is performed not just by professional groups,

such as the Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra, or near-professional groups, such

as the finest ensembles in our conservatories and colleges, but with thousands

of high school bands and community groups, you realize that if you're willing

to give the conductor a certain amount of leeway, as I am, then you've gotta

be prepared to put up with what appears. I certainly wouldn't say I'm

ecstatically pleased with everything that I have heard, but, on the other

hand, I have heard some performances that have such fire and spirit in them

when played by what I would call nonprofessional musicians, that in many

respects I would have to give that recording the nod over a sonically perfect,

technically absolutely polished interpretation by one of the professional

groups.

BD: So then you're looking for a little more heart.

AR: Well, every composer,

I believe, is always looking for that. We may scream and rant and rave

and tear our hair and curse the conductor and the players up and down for

missing one note out of 22 thousand in a piece, but at bottom we always go

for the overall spirit. In the final analysis, where it really counts

is out there in the audience, not up on stage. You learn in time, or

at least I have learned in time, that you can afford to forget about those

(hopefully) relatively few technical slips, that at the moment you could cheerfully

boil them all in oil! [Laughter]

BD: When you're sitting down with a blank piece of music paper, for whom are you writing?

AR: That's a good question. First of all, I have to satisfy myself. Now they say that the difference between a true creative artist and a hack is that the hack sits down, first of all, to satisfy his audience, his employer, whoever. And as long as he satisfies them, he can't be too much concerned with whether he's satisfied himself. "If it sells, baby, it's good." I imagine there are people like this but I can honestly say that I have never had that feeling with any of the pieces of mine that have really stuck in there. Just yesterday my Russian Christmas Music was 42 years old, and it's been in the repertoire and consistently played ever since. I have a difficult time thinking back to the sort of person that I was 42 years ago, but I know when I was writing it, I was just so in love with music, and I would no more have thought of committing an indiscretion than I would have thrown mud at a beautiful woman! I had to do it first in such a way that the tones went where I heard them in my mind and in my heart, and I had to get it done in such a way that it sounded to the best of my ability. Now the version of the Russian Christmas Music that has been in print since 1968 is really the third version of the music. There were three versions: the original, the first revision, and the second revision. In the second and third revisions I did not change the music, but I changed the way I had written for the instruments, to get them to sound the way I felt the music needed it. Those were the changes, it's not that I rewrote the work!

BD: Based on your growth and experience in working with instrumentation.

AR: Exactly. You have a very interesting situation like this with one of the greatest of composers, Brahms. His first piece of chamber music was the great B major trio. Thirty years later he recast it, but if you read his letters and the comments of the people with whom he discussed it, he realized he could only go so far because otherwise it would no longer be that work. So he just touched it up here and there. He replaced a couple of modulations with something that thirty years of experience had helped him to see as a smoother, more interesting way of doing it. But as he himself said, he could not afford to tamper with the basic musical ideas too much, because otherwise it would no longer be the same work. It would be an entirely different piece!

BD: Better to start with something new.

AR: Absolutely.

BD: I like to ask living composers about this. We seem to be on this binge of going back for original versions. You say you have three versions of the Russian Christmas Music...

AR: [Interrupting] But only one is available.

BD: Well, the others must exist somewhere in an archive.

AR: That's true!

BD: So someone might be

able to dig it up and be able to perform it. "Here is the original

version of Alfred Reed's music." Is that a valid performance?

AR: To perform it, I don't know. I certainly would not destroy every copy of something that seems destined to be around, because there may be some people who would want to compare and do an analysis, or a graduate thesis or a doctoral dissertation. I would say such people certainly should have the right to see these things. Only one version, the last version, is published, and that is the most readily available. As to performing any of these other versions, believe it or not, the question is not in my hands. It has to be the individual conductor. The audience, in effect, "trusts" the conductor to make the particular choices for them, so this is in the hands of the conductor.

BD: Would you object, though, to having a recording of the three different versions all available?

AR: Well, I don't think

I would object. I don't think that any record company would wish to

do this, unless it were for archival purposes and to be kept in a library.

I certainly wouldn't object to that at all.

* *

* * *

BD: Is composing fun?

AR: Oh, it has to be, absolutely,

Bruce. I can't speak for every composer, I can only speak for myself,

but if it isn't fun, I don't see how I could justify the amount of time that

it takes, in these big works, just to put the notes down on paper after the

creative choices have all been made! That's not what takes all the

time; it's the sheer physical labor and the time that that labor necessarily

demands! When you stop to think about it, we have not really changed

the way music has been written in over one thousand years. We have better

pens, better ink, better paper. We even have computers today but still,

whether it's with a pen or the computer, it's one man punching down, writing

out, whatever, one note at a time. Now if I could figure out some way

where I could write six notes at once, then maybe we would've made an advance.

So it's gotta be fun doing it, or else how can you possibly justify that

much time out of your life? And if you're married and have a family,

how can you justify taking that much time away from them?

BD: Are you optimistic about

the future of music?

AR: Oh, absolutely. I feel that music is one of our deepest

psychological needs. It's not something like the polish of civilization

has brought this forth. Music goes back to the time before literate

speech, in the sense of verbal communication, was even thought of.

I was interested to find that this was a question that had occupied Charles

Darwin in the last years of his life. You won't find this in The Origin of Species (1859) or in any

of the other books that he wrote dealing largely with plant and other organic

evolution, but in his last book, The Descent

of Man (1871). In his notes and journals and letters, he comes

back again and again and again to the concept of music as the only way of

communication in those eons of time before speech, such as we know it today,

was invented. He called it a nonverbal form of communication and the

example he gave is a very interesting one. He said that, obviously,

the concept of the division of labor existed in those pre-primitive prototype

societies. Women and children did not go out to hunt the boars and

mammoths and saber-toothed tigers for flesh. That was done by the young

men, the strong men, and the women stayed home, kept house, had the children

and tended to them. The old men passed on the literature, the stories,

the tribal experience, and then the young men would come back and they had

no way of telling the home folks what they had seen and done on these hunting

expeditions. So they acted it out to the accompaniment of drums and

other rhythmic sounds, and this is where we get the whole idea of drama and

music from. Now that was what Darwin believed. And you know what?

That's not a bad explanation, as far as I'm concerned.

AR: Oh, absolutely. I feel that music is one of our deepest

psychological needs. It's not something like the polish of civilization

has brought this forth. Music goes back to the time before literate

speech, in the sense of verbal communication, was even thought of.

I was interested to find that this was a question that had occupied Charles

Darwin in the last years of his life. You won't find this in The Origin of Species (1859) or in any

of the other books that he wrote dealing largely with plant and other organic

evolution, but in his last book, The Descent

of Man (1871). In his notes and journals and letters, he comes

back again and again and again to the concept of music as the only way of

communication in those eons of time before speech, such as we know it today,

was invented. He called it a nonverbal form of communication and the

example he gave is a very interesting one. He said that, obviously,

the concept of the division of labor existed in those pre-primitive prototype

societies. Women and children did not go out to hunt the boars and

mammoths and saber-toothed tigers for flesh. That was done by the young

men, the strong men, and the women stayed home, kept house, had the children

and tended to them. The old men passed on the literature, the stories,

the tribal experience, and then the young men would come back and they had

no way of telling the home folks what they had seen and done on these hunting

expeditions. So they acted it out to the accompaniment of drums and

other rhythmic sounds, and this is where we get the whole idea of drama and

music from. Now that was what Darwin believed. And you know what?

That's not a bad explanation, as far as I'm concerned.

BD: Speaking of music and

drama, have you written an opera?

AR: No, not yet, but I have done a great deal of dramatic music in my early days, when I was writing for radio in New York on NBC and ABC. In those days I used to do dramatic music for some of the great shows. The show that represented the highlight of my career in those days was put on by the American National Red Cross dealing with the Korean War. The title was Parallel 38, a one-hour drama. The script was written in blank verse by a Canadian, with Raymond Massey as the narrator. I had 42 men of the NBC Symphony Orchestra as the performing group and there was enough music in there, believe me, to write a good deal of one act of a full-length opera. So I've had a lot of opportunity to write dramatic music, but the way my personal career developed, I don't wish to appear arrogant, but I must be one of the most commissioned composers in the country. I've had 62 commissions in the last 33 years, and I'm booked up solidly through 1989 at present and these are all for what we would call concert works. So for me to take two or three years out to write an opera, particularly at this time of day, with the inherent difficulties - largely financial - of staging something such as this, would be a tremendous sacrifice. But that doesn't mean that I may not make it yet. The big problem, of course, is not a matter of writing music, it's a matter of a first-class libretto. That is what the American musical theater, in turn, has done for serious music. It's hard to see the influence of Johann Strauss, Emmerich Kalman, even Sigmund Romberg and Rudolf Friml operettas in such a hard-boiled musical as West Side Story, or Guys and Dolls. I think it really just grew here, and we've learned certain ways of putting music, words, scenery, action and choreography together that simply will not permit us the leisured approach of a Wagner or a (Richard) Strauss, where the stage picture for so long is absolutely motionless, while overwhelmingly great music wells up from the orchestra pit. So, you see, the point is that today, a playable book, a script that translates well in terms of movement by flesh-and-blood people on the stage, is really what the music has to be hung on! Because to do it the other way, of the book existing merely for the sake of providing the composer with so many opportunities for arias, duets, trios, choruses, and then orchestral music, I don't see where that has too much of a future, given the economic and social circumstances under which we live today. When you stop to think that the first act of Götterdämmerung alone runs almost two full hours, and that there are two acts yet to come! Talk about designs, talk about arches, talk about formalistic structure. Such a two-hour structure - what can I say of it? It's never been done before, and it'll never be done again! It is one of the high spots of musical composition, but today we simply don't have the audiences for it! We've gone beyond that, and I think any composer that writes an opera today that runs longer than about two and a half hours is deliberately loading the dice against himself.

BD: And yet we still have the audiences that go to Götterdämmerung.

AR: Ya, but they are minority

audiences. The question is whether a new work could be found that would

command a sufficient number of performances to even begin to pay off the

investment that such a work today would require. And today, audiences

tend to hear what they see. And not, as with Wagner, so many times

you must see what you hear. It's possibly a subtle distinction, but

it's there. And we don't wanna see a 300-pound prima donna acting the

part of a 19-year-old Brünnhilde who defies Wotan out of the sheer loveliness

of youth and her great spirits. We put up with this when a Flagstad

or a Nilsson comes along, but we gently veil our eyes to what we see, and

we see it in the music that we hear! In Wagner's music, we see Brünnhilde,

as it says in the score, jumping from rock to rock singing "Ho-jo-to-ho!"

It's tremendous, but I can't see Madame Flagstad or Madame Nilsson jumping

from rock to rock in full armor! If Walt Disney were to have taken The Ring of the Nibelungen in hand and

really done it seriously, we would've had the perfect performance of it.

Who knows? Maybe they'll still do it.

BD: This has been a great

pleasure. Thank you for being a composer.

AR: [Chuckles in a sudden

outburst, clearly pleasantly surprised to have been thanked in such a way]

Thank you, Mr. Duffie. Thank you for having me as a guest. If

I may say last word, and again, I hope this will be taken slightly controversially:

From where I sit, what I have seen and heard and what I have done in the

last 35 years of my life, I have to say that the most exciting prospects

today, from the point of view of developing audiences and offering opportunities

for many composers to try out many, many different ideas is, largely because

of financial considerations, no longer the symphony orchestra, but the wind

orchestra. Because when all is said and done, we can argue aesthetics,

we can argue art, we can argue communication. But we cannot argue the

fact that 46 salaries are a lot less than 85, 92 or 108.

This interview was recorded in Chicago on December 16, 1986. Portions

were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1991 and 1996. This transcription

was made and posted on this website in 2008.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.