CONVERSATION PIECE:

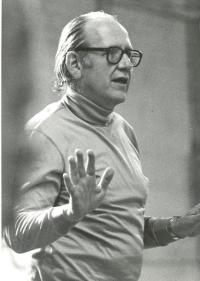

Director Nathaniel Merrill

By Bruce Duffie

Nathaniel Merrill is one of the great opera directors.

He might blush when reading that statement, but he knows his own value

as well as the abilities of singers and the merits of the operas he produces. In an age when the stage-director has come under

fire from many corners, Merrill consistently brings the spectacle of grand

opera to life without resorting to tricks, gimmicks, or other extraneous

devices.

For many years, Nat Merrill was associated with

the Metropolitan Opera, first as assistant, then as leading producer. Some of his productions have become legendary, including

Die Meistersinger and Die Frau ohne Schatten. The Strauss work is widely considered the “real”

opening for the new Metropolitan Opera House at

Besides the Met, Merrill has also been associated

with other companies both large and small, and is now himself in charge of

the Opera

He has been in

Bruce Duffie:

All phases of opera need to be planned so far in advance these days. Do you, as a director, like being booked so far ahead?

Nathaniel Merrill: Oh yes. We don’t have anything to compare with the security of a regular position, so all we have is the last thing we’ve done. And, I like working well ahead. Most productions nowadays, as you well know, are conceived between a year and two years ahead of the time they’re actually done.

BD: Do you get involved in the scenic design, also?

NM: Absolutely. The stage director of a new production is the one who hires the scene designer. I don’t do anything unless I can use the scene designer I want to have for it. Then I work with the scene designer on what the concept should be. It would be unfair to say the concept is mine, but rather it’s a collaborative effort. I usually like to do it in the period that the designer works best in, so that means you pick a designer who you know has certain period-fortes – like Cecil Beaton with the Elizabethan period.

BD: So you take into account the personalities involved.

NM: Oh I think you have to. Is it going to be projected; is it going to be realistic; is it going to be stylized, and if so in what way? Therefore you pick a designer who works well within that spirit.

BD: Do you conceive the production with a certain cast in mind?

NM: The cast is chosen by the theater, and often before they get to designers and directors. We are hired less far-ahead than the leading cast members. So I am told who the stars will be, but I’m often asked what I think about other castings.

BD: What about the conductor?

BD: What about the conductor?

NM: The conductor may or may not be involved yet. Sometimes pieces are done for conductors, as they are for tenors, but the problem now is to find somebody how has the time to spend – a month doing preparation, and two months playing it in the theater – and that’s always difficult. No conductor wants to stay in the same place for three months. They all seem to have too many other things to do, too many other monies to be made doing guest appearances and so forth.

BD: What happened to the artistic flame that burned within?

NM: Oh, that still burns within. You can be very artistic and still travel. (laughter) See, it’s easier for the director because our planning can be done well ahead. Sometimes, as in the case of Chicago, one comes in the summer and lights the opera; or, as in San Francisco, one comes in the summer and stages the chorus and lights it. Then we come back for the production period, but the total time of our having to be away from home is not more than four to five weeks, so that’s a good deal less than a performer or conductor who has to stay the next six weeks for the performances.

BD: Can a production get over-rehearsed?

NM: Oh absolutely. The whole point is to get it so it all comes together at the right moment – like making a soufflé. You pace yourself very carefully, and sometimes just don’t rehearse. It’s not good to tire people for no benefit. You want to keep that real excitement for the premiere. You don’t want the performers to know whether it’s going to go well. The only person who should know that it’s going to go well that first night is me. You want the singers to have the little nervous edge about it.

BD: How do you keep that tension for the third or fifth or eighth performance?

NM: I don’t know – I’m never there.

BD: Do you care?

NM: Very much so. It’s my performance, but then they keep it going on the edge because the public is there and they know it’s a success. Once you know it is a success and the doubt is out of it, then it goes along.

BD: When you’re in a theater for other operas, do you stay in touch with those later performances of earlier productions?

NM: Yes, then I am in control of those later days and can alter little things that happen which could be done better. At every premiere, there are ten or twelve little notes of things that we can do better. With one more dress rehearsal, we might have caught some of those, and we might not. At the premiere, we have a public in the house which is always different.

BD: Should the public be invited to the dress rehearsal?

NM: I think the public should, but the critics should not. They are not able to cope with a rehearsal situation where details are still to be worked out, and if they do come to dress-rehearsal, they write their reviews based on that. You don’t wash away their first impressions. They only come to the premiere to make sure the announced singers sang.

BD: Would you rather the critics came to a later performance?

NM: No, I think we gear it to the first performance, and normally it’s the top of the excitement and the top of the quality.

BD: Does it level off after that or go down later?

NM: It can go any one of three ways. Sometimes it goes up after the premiere.

BD: Does your direction take into account

in any way the radio broadcast – either that first night as it is here in

NM: No, not a bit. It’s the same with the television. “Live from the Met” is exactly what it says – live. You are there as if you were in the seat where that camera is. Nothing is done for television or revised for television except for boosting the lighting so that it’s acceptable for the camera.

BD: Is it really “live” from the Met even when it’s delayed by a day or two, or several months?

NM: It is “live” from the Met because the tapes are untouched. It is not an edited tape. Four or five cameras are in use, but the decision as to which camera is in use at any moment is made during the performance. That, by the way, I do not agree with. If you took the five cameras and edited it, you’d have a much better tape. You wouldn’t have people walking in front of other people as so often happens.

BD: Would you like to go in and tamper with the tapes?

NM: Absolutely. You would still have a “live” performance in the sense that we did not go and re-record anything. The flaws and the great emotional things from the live performance would still be there, but technically you would have a better picture. You wouldn’t miss pictures of things you are supposed to see because the camera is looking at something else. The technicians come in with their cameras for one performance ahead of time and make a tape. Then they look at the tape and from the experience with that tape they go ahead. “Live from the Met” is exciting because it is live from the Met, and that kind of quality is very good, but it does not produce the best television.

BD: Do you feel opera works well on television?

NM: I don’t think so, no. I think certain operas works very well on television. Bohème works well because it’s a very realistic opera – like a play. My Rosenkavalier which opened the season a few years back I thought was a bore on television. Part of why it was a bore is the technique, and the technique at the Met is to do nothing but close-ups. There are no grandeur scenes, no scenes that show the entire stage. Very often in a scene, you are working three or four different ideas at once. There are various things happening all at once to the same music, and obviously, with a close-up of one of these, you are missing the others. And, I feel four hours is too long on television.

BD: Would you do something specifically for television?

NM: Absolutely. One

of the things I can do in

*

* * *

*

BD: Are you in favor of eliminating intermissions

as they often do in

NM: Sometimes, yes. Where you have two scenes that are short, it’s silly to have a 20 minute intermission between them – Rigoletto and Bohème in four acts for example. We did Elisir in two acts for the first time and that was my doing. I think the average theater-goer likes one intermission. They can go 1 ½ hours or even a few minutes more without getting out of their seats. But the German way of doing The Marriage of Figaro with just one intermission is much too long.

BD: But then it’s just the

same proportion as Così or Don Giovanni.

BD: But then it’s just the

same proportion as Così or Don Giovanni.

NM: Well, Figaro done that way seems longer. And I don’t know of any complete performance of Così that would not be too long.

BD: So you believe in cuts, then.

NM: Absolutely. We’re doing opera for our audience and they live with a different taste than they did years ago. Over the years, our viewing habits and our attention-span is a good deal less than it was, and we don’t have the time to spend in the theater that we did before.

BD: Are we getting conditioned to a seven-minute segment and then a commercial, as it is on the tube?

NM: I think that has a great deal to do with it, but people don’t have that much time in a life that moves very fast now. Four hours is a lot of time for a businessman. I approve of making cuts where we don’t hurt the musical part of the score and the story part of the score, and where we make it possible for a bigger success to result from having cuts. There are certain times that cuts don’t work. For instance, indiscriminate cuts in Wagner often mean that full, draggy parts are left out, and parts that worked before become dull, draggy parts that don’t work then. And really, any cut in a Wagner opera destroys the form of the piece which he wrote. The third act of Rosenkavalier does not work without cuts. It is humorous, it’s ingenious, it reads very well, but it’s too long.

BD: Would it work for an audience which was at leisure?

NM: I don’t think so – not even if they all

understood German. But with an American audience

which does not understand German – which is not a leisure

audience, and which, let’s face it, is waiting for the trio and the duet

at the end – you don’t want to be too tired to revel

in the last twenty minutes of the opera. The

place to cut, when the last part is too long, is a good deal earlier in the

opera so the ending comes a lot earlier in the evening.

Purists hate it, but I’m also in favor of cuts in Meistersinger. The one here in

BD: Are there any operas where you would not make any cuts under any circumstances?

NM: I don’t think you need to make cuts in

Bohème. It’s a short opera

and every scene works dramatically just as it is. As

far as I know there are no cuts to make in that opera unless you want to

leave out the children for economic reasons. Most

Puccini is hard to make cuts in, but those were mostly written in this century. When you get back to the operas with cabalettas,

do you sing both verses or do you sing one? That

decision is based on what you think the public will want at that moment. If you’ve got a singer who will really knock the

people over, why not do it twice? Then the cabaletta

is repeated. The audience learns the tune and

when it comes back the second time they can almost hum it along. And since most cabalettas are either

BD: When you’re studying an opera for the first time, do you approach it from the music of from the play?

NM: From the music first, then the play, then back to the novel if there is one. We’re trying to find what the composer had in mind and duplicate something visually on the stage.

BD: Then how do you balance what the composer wanted with what the public expects?

NM: You do it in a style which relates to modern audiences. You don’t have to do an opera in the style which the composer would have known. In any opera that you do, the production scheme and the plot of the opera have to be handled in such a way so that your premise for the production is related to the audience that you’re performing for. That will make the production, even though you’re highlighting the same values and trying to do the same thing. We’re trying to do what the composer would have done were he alive now, and were he relating to this audience. You know, composers were not people who sat in closets and didn’t care about the audience reaction. Mozart wrote to his father expressing his delight at the reactions he received.

BD: And Verdi always said to look at the box office!

NM: Right, and we do, too. There is nothing worse than doing something that is dull. That is why I chose Otello to open Opera Colorado. I wanted an opera that would grab the public out there, and in the first fifteen minutes would produce one of the largest urinary pauses after the first act in history. And that is that kind of opera. Turandot is another opera like that. It builds from the very first note, and goes uphill all the way.

BD: While we’re there, tell me more about your

company in

NM: I’ve been associated with

BD: I know your casts there have been first

rate. How do you get the biggest stars in opera

to come to

NM: I think they come because they trust me and know that what I’m mixed up in will be exciting and not be a fiasco for them. And I think they are fascinated with opera in the round. Placido Domingo said that he’s always bored with having to keep turning back so his eyes can cross the conductor to find out where he is. Being able to turn around and see the conductor on a television screen will be an interesting technique.

BD: Doesn’t the point where the orchestra and conductor are automatically become “front?”

NM: No, that becomes

BD: Then do you have to work extra hard to see that no one in the audience is left out?

NM: There enters the choice of the repertoire. If you think about it, Bohème never has a solo scene. Except for Mimì’s entrance in the third act, there is not one place where there is only one solo singer alone on the stage. The arias are really dramatic duets, meaning the aria is sung to somebody else.

BD: So you would never do a Handel opera?

NM: The public would not come. They would be more likely to come to Wozzeck than a Handel opera.

BD: Whose fault is it that the public stays away from certain works?

NM: It’s an educational process which we

have to whittle away at, and which we are whittling away at in many centers

of the

BD: Is the star-system a mistake?

NM: Not at all. How can you call it a mistake? Football is based on it, basketball is based on it, motion pictures are based on it, television is based on it, our lives are based on it. And opera is based on it 100%.

BD: Can opera be done without stars?

NM: Certainly it can be done.

BD: Would you ever do an opera without stars?

NM: No, because I am a star in my own right. So opera without stars would mean doing it without

me and without a star designer. The star of Madame Butterfly [seen on PBS in 1986] is Hal Prince.

BD: Are you the star in all your productions?

NM: Not when we have a cast of sensational world-class singers. I hope I’m not the star. I never have wanted to hear about “Nat Merrill’s production” of this or that like you hear of “Franco Zeffirelli’s production” of something. I think that’s a disservice to the composer. I would rather be associated with a production with the composer’s name rather than with my name. I don’t have that kind of ego-complex.

BD: How do you put up with singers who do have that kind of ego-complex?

NM: You fit them into the pattern of what you are doing. Eventually, you talk them into it.

BD: Do you always win?

NM: Almost always. The trick is not to back yourself into a corner you can’t get out of – or more important, not to back your opponent into a corner they can’t get out of. Leave them a graceful exit. You’d be surprised how that works. After all, you’re trying to do something which is new and sometimes different with somebody who has maybe had a long association with doing it a certain way.

BD: Do you approve of opera in translation?

NM: Very much so. I think it’s better for an audience in translation that does not understand the original. The problem comes when we want international singers who make their living doing these operas in the original languages. But with young American singers, it should be done in English. I think it’s important that young people come to the opera and enjoy it; that’s our audience of the future.

BD: How can we get more people to come to opera – either adults who have never been, or children?

NM: Don’t play down to kids and give them

inferior productions with inferior singers. Don’t

make the mistake the Met does of giving students matinees with young singers

who really can’t cut the mustard. Too often,

they are just thrown on the stage, and they need more rehearsal than the

famous singers do. You want to turn people on,

and adults are the same – you want to turn people on when they first get

there. If you don’t “get” somebody within the

first five minutes, you’ve lost them.

Bruce Duffie continues his work at WNIB, Classical

97 in

Nathaniel Merrill, opera pioneerPublished September 10, 2008 at 11 p.m.

Like an old-time pioneer leaving the big city to seek his fortune out west, Nathaniel Merrill gave up a brilliant career as resident stage director at the Metropolitan Opera and came to Denver in the early '80s to make history. Against all odds, he built a world-class opera company in a city that previously had struggled to sustain a regional one. Mr. Merrill died on Tuesday at 81 of complications from Alzheimer's disease. But Opera Colorado, the company he created and directed, lives on. "If it hadn't been for him and Louise (Mr. Merrill's wife, the late chorus director Louise Sherman), we wouldn't have Opera Colorado," said Steve Seifert, who became general director after Mr. Merrill resigned that post in 1998. "This is a loss to a community he did enormous service to. But we need to celebrate what he did."

"I'd been wanting to leave the Met," he told the Rocky in 1991. "I was bored to death - I guess I was having a midlife crisis." With the Met on strike in 1980, he visited Denver and saw an opportunity to start a company and work in the round, since operas would be staged in circular Boettcher Hall. "I had never done opera in the round and had never seen it in the round," Mr. Merrill said in that 1991 interview - admitting that he lied about his inexperience to local supporters. "He gathered people here who just loved opera," said Ellie Caulkins, an original board member and namesake of the Opera House that opened in 2005. "We were ready to have opera here," Caulkins said. In 1983, the company debuted. Calling on some of his illustrious opera friends, Mr. Merrill directed Verdi's Otello, with James McCracken and Eva Marton, and Puccini's La Boheme with Catherine Malfitano and a promising tenor named Placido Domingo. "Nathaniel Merrill was a wonderfully talented director who I had the great fortune of working with during my debut season at the Metropolitan Opera," Domingo said in a statement from Los Angeles released late Wednesday. "In fact, his new production of Il Trovatore there in 1969 was the first time I appeared in a new production at the Met. It was a beautiful staging with a phenomenal cast and Zubin Mehta in the pit, so I was really a newcomer compared to everybody else. Nat’s formidable talent and experience was quite welcome and reassuring, and we all enjoyed a great success. In subsequent seasons, I had the pleasure of performing in several of his classic Metropolitan Opera productions. Later, when Nat launched Opera Colorado in 1983, I was very happy to be work again with my old colleague in his exciting new venture, and I know that he took great pride in bringing that company to life." Another who came aboard was Francesa Zambello, then a young assistant director and now one of the world's most sought-after directors. "I helped Nat start (Opera Colorado)," she said in a call from London. "It was a great learning experience. He's really the person who got me started." Many laughed at his dream, she recalled. "People in Denver were very cynical. It takes a lot to convince people to give to opera." Mr. Merrill had been in Colorado previously, staging 11 productions at Central City Opera from 1958 to 1963, including a fabled Aida in 1960 with Beverly Sills. In 1972, he served as artistic director at Central City. "Nat and (noted director Robert) O'Hearn did a lot of experimental things together at Central," observed former general director John Moriarty. "He had some grand ideas. We called him Cecil B. DeMerrill." Not everything went smoothly at Opera Colorado. Money problems emerged periodically, starting with year two in 1984, and some subsequent productions failed to draw big houses. Yet, there was never a dark season. Things seemed to come apart for Mr. Merrill in 1998 when, during rehearsals for Carmen at the Buell Theatre, his wife, Louise, succumbed to cancer, and the singer portraying the title character broke her arm. A month later, according to Seifert, a mutual decision was reached by Mr. Merrill and the opera board that the founder would resign. Though he had no further interaction with the company, he continued to attend productions until the effects of Alzheimer's forced him to become a permanent resident at Aspen Siesta nursing home, where he died. Born in Newton, Mass. on Feb. 8, 1927, Mr. Merrill attended Dartmouth College and later studied at the New England Conservatory of Music and Boston University. Before Louise Sherman, he was wed to singer Barbara Curry. In 2001, Mr. Merrill married Pamela Meyers, a longtime Opera Colorado supporter. Besides Mrs. Merrill, survivors include sons Hank, of Bedford, Ind., and Christopher, of New York City; and daughter Linda Ely, of London. A private memorial will take place this week. Plans for a public memorial will be announced later in the year. Contributions may be made to Opera Colorado, 695 S. Colorado

Blvd., Suite 20, Denver, CO 80246 or online at operacolorado.org. |

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on December 2, 1982.

This transcription was made and published in The Opera Journal in June, 1986; it was

slightly re-edited and posted on this website in 2009. Additional photos

and links added in 2015.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.