BJ: It was totally different because I had sort

of kept away from the Conservatory once I had finished my studies.

Coming back to this school through the big doors, so to speak, was an incredible

experience because all the students he had then have become famous since.

They represented a very interesting tendency. In my generation, we

were brought up sort of in twelve tone, post-war, around Boulez and domaine musical, and these men and women

— there were some women, too — were not interested in that anymore.

They were building something new, which became what is known as spectral

music. These were people like Levinas and Grisey and Murail, and they

were all his students at the time.

BJ: It was totally different because I had sort

of kept away from the Conservatory once I had finished my studies.

Coming back to this school through the big doors, so to speak, was an incredible

experience because all the students he had then have become famous since.

They represented a very interesting tendency. In my generation, we

were brought up sort of in twelve tone, post-war, around Boulez and domaine musical, and these men and women

— there were some women, too — were not interested in that anymore.

They were building something new, which became what is known as spectral

music. These were people like Levinas and Grisey and Murail, and they

were all his students at the time. BD: How was it done?

BD: How was it done? BJ: No, certainly not. I’ll tell you a story

about that. This was a time when that kind of initials came up in today’s

world. It was a way of defining, shall we say, the nature of the piece,

which was to be empty and then to be filled with something. It starts

out like a very, very, sort of desert kind of music, and then it gets fuller

and fuller and thicker and thicker. That was more or less the idea

that put in those initials. But the initials do mean something, and

it means a lot of things. Darius Milhaud — he was one of my teachers

— when I sent him the piece, he sent me a very funny letter giving all sorts

of interpretations to those initials. One of those was, in French,

Jolas Droît Écrire [Jolas

Must Write]. The other one was Juliet

des Ésprits which was the title of a film by Antonioni or Fellini!

[Both laugh] And one of the instrumentalists who played it the first

time said, “Oh, I know what that means. It means J’ai Des Ennuis,” which means I have

troubles or I have problems.

BJ: No, certainly not. I’ll tell you a story

about that. This was a time when that kind of initials came up in today’s

world. It was a way of defining, shall we say, the nature of the piece,

which was to be empty and then to be filled with something. It starts

out like a very, very, sort of desert kind of music, and then it gets fuller

and fuller and thicker and thicker. That was more or less the idea

that put in those initials. But the initials do mean something, and

it means a lot of things. Darius Milhaud — he was one of my teachers

— when I sent him the piece, he sent me a very funny letter giving all sorts

of interpretations to those initials. One of those was, in French,

Jolas Droît Écrire [Jolas

Must Write]. The other one was Juliet

des Ésprits which was the title of a film by Antonioni or Fellini!

[Both laugh] And one of the instrumentalists who played it the first

time said, “Oh, I know what that means. It means J’ai Des Ennuis,” which means I have

troubles or I have problems. BJ: Hopefully I write for the whole public.

I think, as the years go by, from what I hear I have the feeling that I have

a public which is not exactly the same public as most composers have today.

It’s a public that includes people that I wouldn’t meet normally in life.

Sometimes I meet somebody who says, “I like your music,” and I don’t even

know who he is, or who she is. My hope is that my music will reach

most people — I mean the greatest public possible. Not for glory, but

just because I like to feel that I am not just addressing a small group of

people. I’m not interested in that.

BJ: Hopefully I write for the whole public.

I think, as the years go by, from what I hear I have the feeling that I have

a public which is not exactly the same public as most composers have today.

It’s a public that includes people that I wouldn’t meet normally in life.

Sometimes I meet somebody who says, “I like your music,” and I don’t even

know who he is, or who she is. My hope is that my music will reach

most people — I mean the greatest public possible. Not for glory, but

just because I like to feel that I am not just addressing a small group of

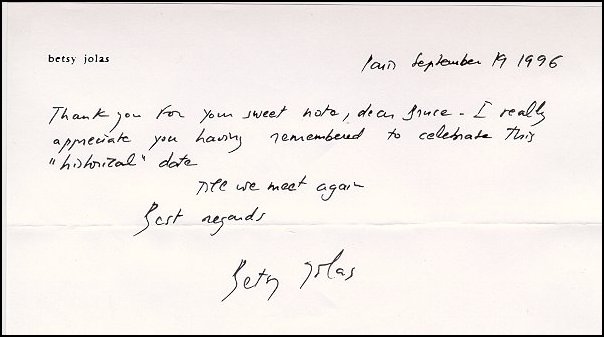

people. I’m not interested in that.As noted in the bio-credit at the bottom

of this webpage, I presented

a program on WNIB for her 65th birthday, and then again for her 70th. I sent her a note about the second program, and she made this lovely reply . . .

|

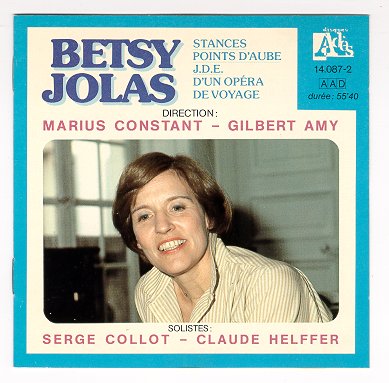

| Betsy Jolas, born in Paris in

1926, is the daughter of translator Maria Jolas and poet and journalist Eugène

Jolas, founder of the well known literary magazine "transition", in which

James Joyce's Finnegans Wake was published under the heading

work in progress. She came to the U.S. in 1940, completed

her general schooling, then started studying composition with Paul Boepple,

piano with Helen Schnabel and organ with Carl Weinrich. After graduating from Bennington College, Betsy Jolas returned to Paris in 1946 to continue her studies with Darius Milhaud, Simone Plé-Caussade and Olivier Messiaen at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique of Paris. Prize winner of the International Conducting Competition of Besançon (1953), she has since won many awards, including Copley Foundation of Chicago (1954), ORTF (1961), American Academy of Arts (1973), Koussevitsky Fondation (1974), Grand Prix National de la Musique (1974), Grand Prix de la Ville de Paris (1981), Grand Prix de la SACEM (1982). Betsy Jolas became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1983. In 1985 she was promoted to Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres. In 1992 she received the Maurice Ravel Prix International and was named "Personality of the Year" for France. In 1994 she was awarded the Prix SACEM for the best première performance of the year for her work Frauenleben. She was elected to The American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1995 and made Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur in 1997. From 1971 to 1974 Betsy Jolas replaced Olivier Messiaen at his course at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique of Paris and was appointed to the faculty in 1975. She has also taught at Tanglewood, Yale, Harvard, Mills College (Darius Milhaud chair), Berkeley, USC and San Diego University, to name a few. Her works, written for a great variety of combinations, have been Widely performed throughout the world by first class artists such as Elisabeth Chojnacka, Kent Nagano, William Christie, Claude Helffer, Kim Kashkashian, and by leading groups : The Boston Symphony Chamber Players, the) Concord Quartet, the Domaine Musical, the Percussions de Strasbourg, the Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society, the London Sinfonietta, the Ensemble Intercontemporain, the Philharmonia, etc. Twelve of her works have been recorded for EMI, Adès, CRI, Erato, Barclay, several of which have been the recipients of grand prize gramophone awards. |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on July 17, 1991.

Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB later that year and again

in 1996. The transcription was made and posted on this website in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.