BD: Are there many more than you know about?

BD: Are there many more than you know about? AI:

They’re more sophisticated, certainly. I think that the musical life

in this country has become very active and very intense over the last few

decades, so that when I look back at what I was like at the age of my current

students, it seems to me they have a much wider acquaintanceship with more

different kinds of music, especially contemporary music. There are so

many schools now in contemporary music, and so many trends, that the danger

is that of trendiness; whereas the danger in my day was simply embracing the

twentieth century and coming of age, as it were. That was a national

thing as well as an individual thing.

AI:

They’re more sophisticated, certainly. I think that the musical life

in this country has become very active and very intense over the last few

decades, so that when I look back at what I was like at the age of my current

students, it seems to me they have a much wider acquaintanceship with more

different kinds of music, especially contemporary music. There are so

many schools now in contemporary music, and so many trends, that the danger

is that of trendiness; whereas the danger in my day was simply embracing the

twentieth century and coming of age, as it were. That was a national

thing as well as an individual thing. AI: Depending on what level you’re talking about,

you can give awards to students or you can give awards to composers who have

been professional composers for a number of years. So in the former

case you’re looking for promise, and in the latter case you’re looking for

the best piece or what seems to be the most individual expression and the

most convincing expression from many points of view. I think that a

really talented, original piece is recognizable by a group of experienced

composers of many different persuasions, and that tends to suggest to my mind

the fact that there is a common denominator of some sort which we ourselves

may not be able to explain, but that we all have a feeling for what it means

to be a good composer.

AI: Depending on what level you’re talking about,

you can give awards to students or you can give awards to composers who have

been professional composers for a number of years. So in the former

case you’re looking for promise, and in the latter case you’re looking for

the best piece or what seems to be the most individual expression and the

most convincing expression from many points of view. I think that a

really talented, original piece is recognizable by a group of experienced

composers of many different persuasions, and that tends to suggest to my mind

the fact that there is a common denominator of some sort which we ourselves

may not be able to explain, but that we all have a feeling for what it means

to be a good composer. AI: Well, I think the obligation of the composer

is to project his ideas. Lots of people can walk along the street and

say they have a wonderful idea, but they can’t put it on paper. Or when

they put it on paper, it doesn’t make any sense to anyone else. What

you have to do is to capture the essence of your own idea and try to project

it as clearly as possible. That’s where technique comes in. You

wear a critical hat as well as a creative hat when you compose, and you have

to keep changing those hats back and forth, just the way a painter will step

back from his canvas and squint at it, and then come back and paint some

more. I think the purpose of the squinting at it is to put himself in

the place of the viewer, in this case. Likewise, the composer is obligated

to put himself in the place of the listener and imagine that this was a piece

written by someone else. Would it make any sense? You don’t even

have to go through that exercise; you know darn well, sometimes, that it

doesn’t make sense. You’re trying to say something and it isn’t coming

through. That means that you as listener are not in tune with you as

composer; you haven’t quite figured out what it is that needs to be clarified

in order to make that idea project across the footlights. It’s like

being an actor. You have to have a sense of timing; you have to know

how to project your lines, your words, your gestures, perhaps even a little

larger than life, in order to make them as clear as possible. I think

this applies to the music of Bach as much as it does to the music of Tchaikovsky.

It’s not a question of hamming it up in a vulgar sense; it’s a question of

your gestures being unmistakable. That’s what I think the composer’s

obligation is, in a nutshell. Of course, this is all a great oversimplification.

AI: Well, I think the obligation of the composer

is to project his ideas. Lots of people can walk along the street and

say they have a wonderful idea, but they can’t put it on paper. Or when

they put it on paper, it doesn’t make any sense to anyone else. What

you have to do is to capture the essence of your own idea and try to project

it as clearly as possible. That’s where technique comes in. You

wear a critical hat as well as a creative hat when you compose, and you have

to keep changing those hats back and forth, just the way a painter will step

back from his canvas and squint at it, and then come back and paint some

more. I think the purpose of the squinting at it is to put himself in

the place of the viewer, in this case. Likewise, the composer is obligated

to put himself in the place of the listener and imagine that this was a piece

written by someone else. Would it make any sense? You don’t even

have to go through that exercise; you know darn well, sometimes, that it

doesn’t make sense. You’re trying to say something and it isn’t coming

through. That means that you as listener are not in tune with you as

composer; you haven’t quite figured out what it is that needs to be clarified

in order to make that idea project across the footlights. It’s like

being an actor. You have to have a sense of timing; you have to know

how to project your lines, your words, your gestures, perhaps even a little

larger than life, in order to make them as clear as possible. I think

this applies to the music of Bach as much as it does to the music of Tchaikovsky.

It’s not a question of hamming it up in a vulgar sense; it’s a question of

your gestures being unmistakable. That’s what I think the composer’s

obligation is, in a nutshell. Of course, this is all a great oversimplification. BD: Do you advise young composers, or even old

composers, to write what they want rather than waiting for commissions?

BD: Do you advise young composers, or even old

composers, to write what they want rather than waiting for commissions? AI:

Yes, that’s an even older work. It was written back in 1949, I

believe, to a poem by Walt Whitman, and is scored for mixed chorus and string

orchestra. I wrote it, I think, while I was at the American Academy

in Rome, and it’s been done a number of times. It’s been done here

in Berkeley by student orchestras, and was done recently at Brandeis University

by their chorus and a professional string orchestra. When I hear that

piece, it’s like looking at a picture of one’s self taken thirty or forty

years ago. It seems very youthful and somewhat naïve to me now,

but I still like it. I wouldn’t write a piece like that now; my style

has changed too much. But I still like the piece. I get a sort

of a kick out of it, and it’s quite effective, actually. But it’s the

work of a young and very enthusiastic composer who is just starting out.

I still have a certain fondness for it.

AI:

Yes, that’s an even older work. It was written back in 1949, I

believe, to a poem by Walt Whitman, and is scored for mixed chorus and string

orchestra. I wrote it, I think, while I was at the American Academy

in Rome, and it’s been done a number of times. It’s been done here

in Berkeley by student orchestras, and was done recently at Brandeis University

by their chorus and a professional string orchestra. When I hear that

piece, it’s like looking at a picture of one’s self taken thirty or forty

years ago. It seems very youthful and somewhat naïve to me now,

but I still like it. I wouldn’t write a piece like that now; my style

has changed too much. But I still like the piece. I get a sort

of a kick out of it, and it’s quite effective, actually. But it’s the

work of a young and very enthusiastic composer who is just starting out.

I still have a certain fondness for it. BD: Then let’s talk about the big work, Angle of Repose. This was a commission

from the San Francisco Opera?

BD: Then let’s talk about the big work, Angle of Repose. This was a commission

from the San Francisco Opera? AI:

Well, yes. I don’t know. I’m just hoping someday somebody

will revive it, but it’s not because it wasn’t well received in San Francisco.

AI:

Well, yes. I don’t know. I’m just hoping someday somebody

will revive it, but it’s not because it wasn’t well received in San Francisco. AI:

There’s an awful lot of opera being written for workshops and university environments,

and I think people should certainly start out by writing modest-sized operas,

like the one I did, which is a manageable thing and can be done by a university.

You can also hire some musicians from the outside if you don’t have an orchestra

that can do it, and you can hire some professional singers; it still is possible

to do it in a university setting. People are being trained

in all the arts of producing operas, and they’re composing them, too.

AI:

There’s an awful lot of opera being written for workshops and university environments,

and I think people should certainly start out by writing modest-sized operas,

like the one I did, which is a manageable thing and can be done by a university.

You can also hire some musicians from the outside if you don’t have an orchestra

that can do it, and you can hire some professional singers; it still is possible

to do it in a university setting. People are being trained

in all the arts of producing operas, and they’re composing them, too.|

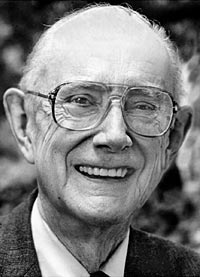

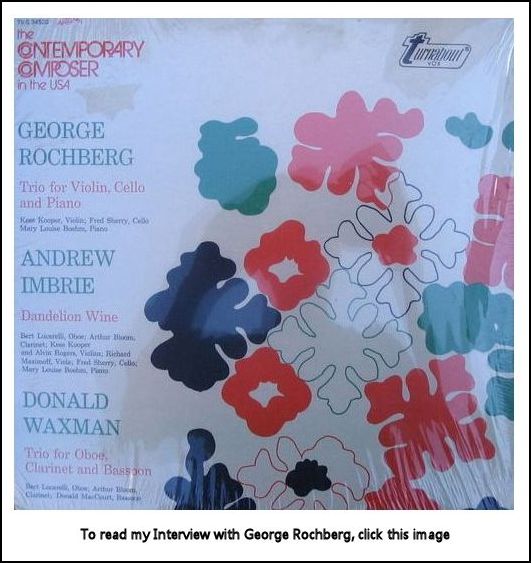

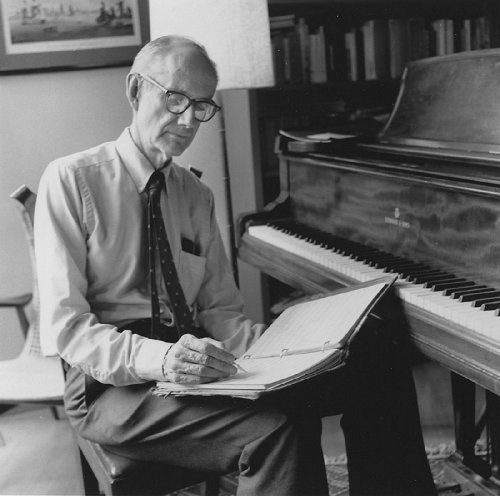

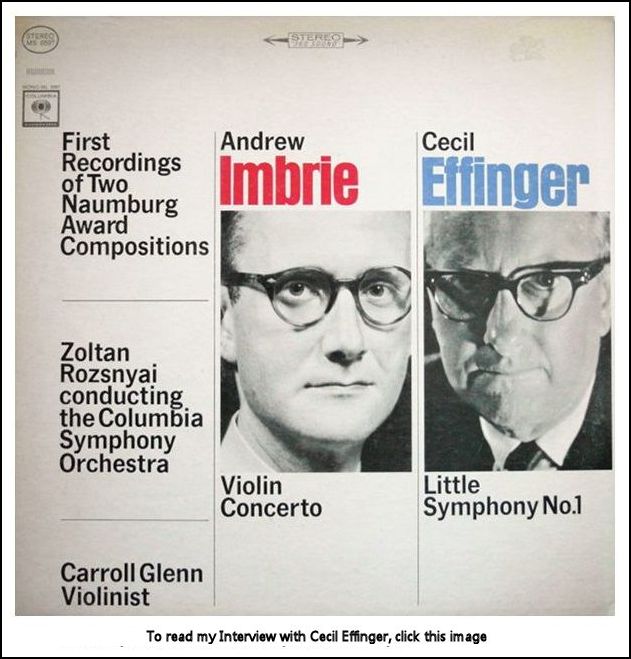

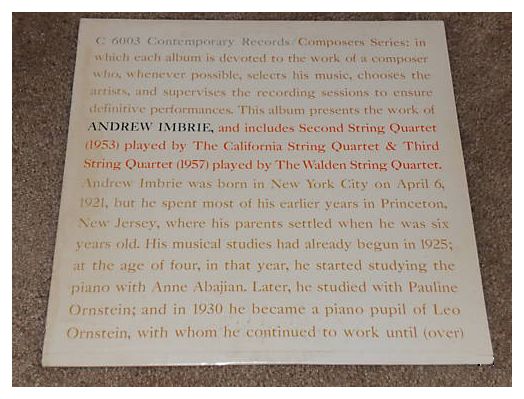

Andrew Imbrie, 86, Composer and Teacher,

Is Dead

By ALLAN KOZINN Published: December 9, 2007 in The New York Times Andrew Imbrie, a prolific composer and influential teacher best known for his harmonically rugged but appealingly lyrical 1976 opera, Angle of Repose, and for a rich catalog of chamber, vocal and symphonic scores, died on Wednesday at his home in Berkeley, Calif. He was 86. His death was announced by Robert Commanday, the retired chief music critic of The San Francisco Chronicle, a longtime friend. Mr. Imbrie was part of the generation of composers who came of age when tonality had fallen from favor, and his music is strongly influenced by search for a new post-tonal language. Throughout his career, his works have used dissonance dramatically rather than harshly, and if his themes were often shaped with the angularity that was the common accent of mid-20th century composition, they typically had an intensity that listeners heard as passionate and direct rather than merely spiky. In his Requiem, for example, composed in 1984 after the sudden death of his younger son, John H. Imbrie, the writing for solo soprano, chorus and orchestra is energetic, assertive and often angry, but its most vehement moments illuminate the tension between the traditional Requiem text and the poetry by William Blake, George Herbert and John Donne that he interspersed between the Latin movements. Other works, like the Serenade for Flute, Viola and Piano (1952) and the Dream Sequence (1986), use gentle timbres, graceful themes and rich, inventive counterpoint to create a sense of magical otherworldliness. And in Angle of Repose, his second and last opera, he wove folk themes and banjo tunes into the otherwise atonal score, as a way of evoking one of the opera’s thematic currents, the settling of the West in the 1870s. “Asking a composer to describe his own style,” he said in a 2001 interview with the Society of Composers Newsletter, “is like asking a person ‘How do you walk? How do you talk?’ We are all subject to influences. Back in the ’50s the European avant-garde tried to eliminate influences from the past by setting up purely abstract mathematical systems to control various ‘parameters’ and thus insulate the composer from unconscious indebtedness. It just plain didn’t work.” Mr. Imbrie was born in New York on April 6, 1921, and began his musical training as a pianist when he was 4. When he was 16, in 1937, he spent a summer in Paris, studying composition with Nadia Boulanger and piano with Robert Casadesus. But a more formative influence was Roger Sessions, with whom he studied at Princeton immediately upon his return from Paris. He completed his bachelor’s degree at Princeton in 1942 and was a Japanese translator for the Army, based in Arlington, Va., from 1944 to 1946. He resumed his studies, again with Sessions, at the University of California at Berkeley. After he completed his master’s there in 1947, he joined the faculty, and continued to teach there until 1991. In 1970, he joined the faculty of the San Francisco Conservatory. Mr. Imbrie also taught at Harvard, Brandeis, Northwestern, New York University, the University of Alabama and the University of Chicago. Mr. Imbrie’s works include five string quartets, three symphonies, and numerous chamber and choral works. His first opera, Three Against Christmas — later renamed Christmas in Peebles Town — is a comic piece about Christmas being banned and restored. It had its premiere in Berkeley in 1964. His last complete work, Sextet for Six Friends, was given its premiere by the Left Coast Chamber Ensemble in February. He is survived by his wife, Barbara, and his son, Andrew Philip Imbrie of Santa Clara. |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on April 26, 1986.

Portions (along with recordings) were broadcast on WNIB later that year and

again in 1991 and 1996. The transcription was made in 2008 and posted

on this website in January of 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.