BD: Does

your knowledge and experience in the scientific field help you relate the

artistic side to people who are only scientists and researchers?

BD: Does

your knowledge and experience in the scientific field help you relate the

artistic side to people who are only scientists and researchers? BD: This

range that you have, does it determine which roles you will sing and which

you won’t sing?

BD: This

range that you have, does it determine which roles you will sing and which

you won’t sing? JH: That’s right.

JH: That’s right.  BD: But in

the end, he is not defeated, is he?

BD: But in

the end, he is not defeated, is he? JH: It has to be a perfectly equal balance, and I’ve tried to

achieve that during my whole career. Each opera and every character

should be researched not by some pattern, but by what is the most important

factor involved. For example, I don’t believe in psychoanalyzing Don

Giovanni. It’s not written in that vein. When I did my first

Boris Godunov, I asked various stage directors about the character and got

a huge diversity of opinion. All they had in common was to say he was

crazy. Well, I was going on a tour of various universities for about

eight weeks before doing the opera at the Met, so I interviewed ten psychologists

and psychiatrists. I would read them the basic libretto and ask what

was wrong with the man and how he would act. Unfortunately, I got just

as much diversity from them as I did from the stage directors! That

shattered my faith in the field of psychiatry and psychology.

JH: It has to be a perfectly equal balance, and I’ve tried to

achieve that during my whole career. Each opera and every character

should be researched not by some pattern, but by what is the most important

factor involved. For example, I don’t believe in psychoanalyzing Don

Giovanni. It’s not written in that vein. When I did my first

Boris Godunov, I asked various stage directors about the character and got

a huge diversity of opinion. All they had in common was to say he was

crazy. Well, I was going on a tour of various universities for about

eight weeks before doing the opera at the Met, so I interviewed ten psychologists

and psychiatrists. I would read them the basic libretto and ask what

was wrong with the man and how he would act. Unfortunately, I got just

as much diversity from them as I did from the stage directors! That

shattered my faith in the field of psychiatry and psychology. BD: Is it

because of the numerous cases of singers doing big roles at 20 and 21, and

by 26 they are burned out?

BD: Is it

because of the numerous cases of singers doing big roles at 20 and 21, and

by 26 they are burned out? JH: Right.

JH: Right.

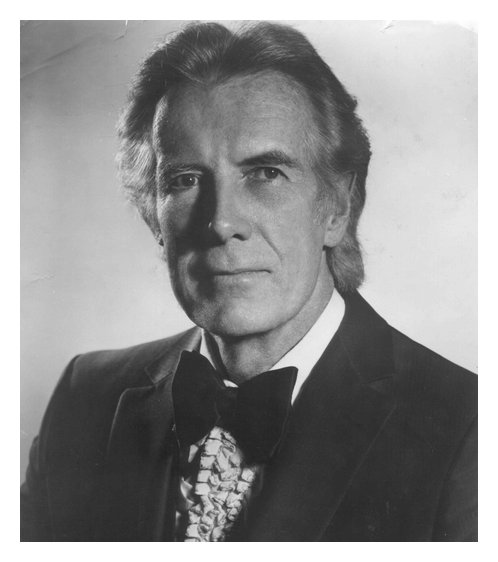

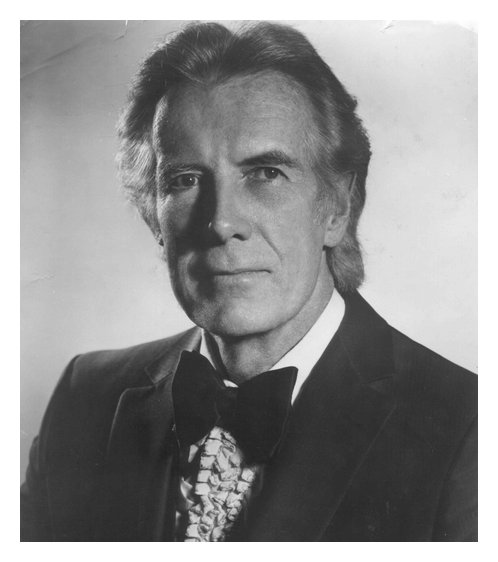

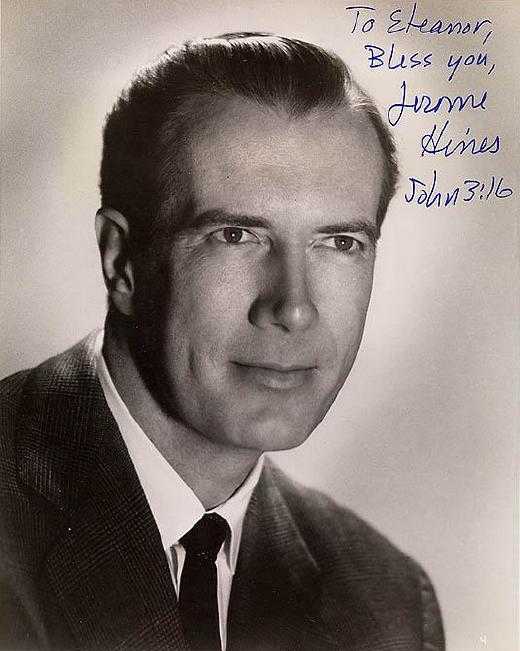

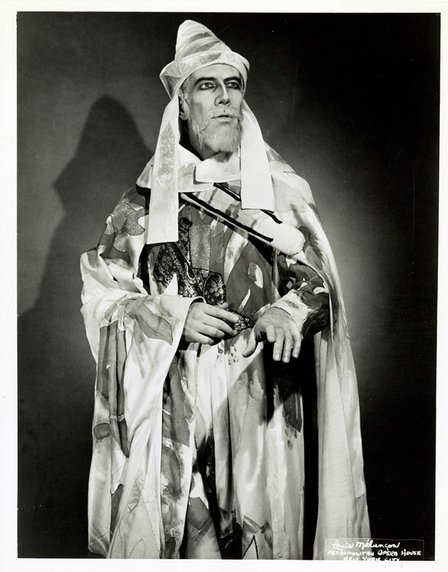

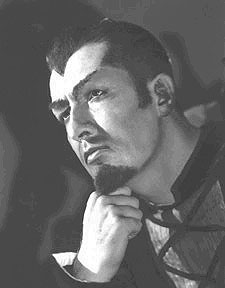

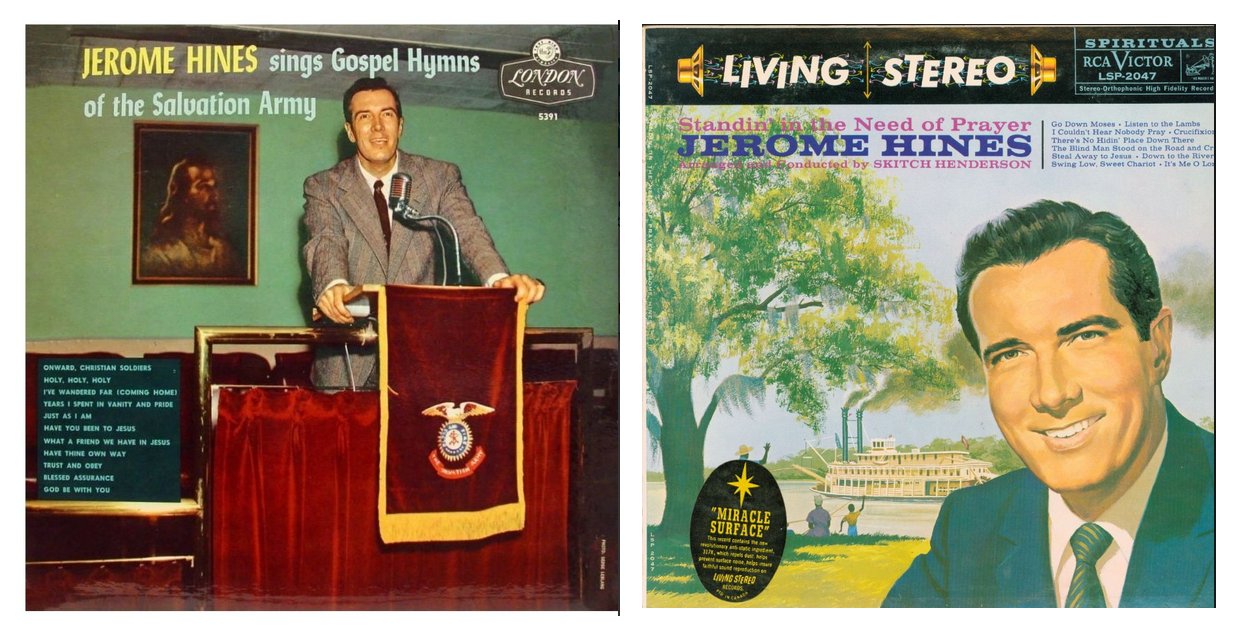

Jerome HinesLong-serving bass at the Metropolitan Opera, New

York

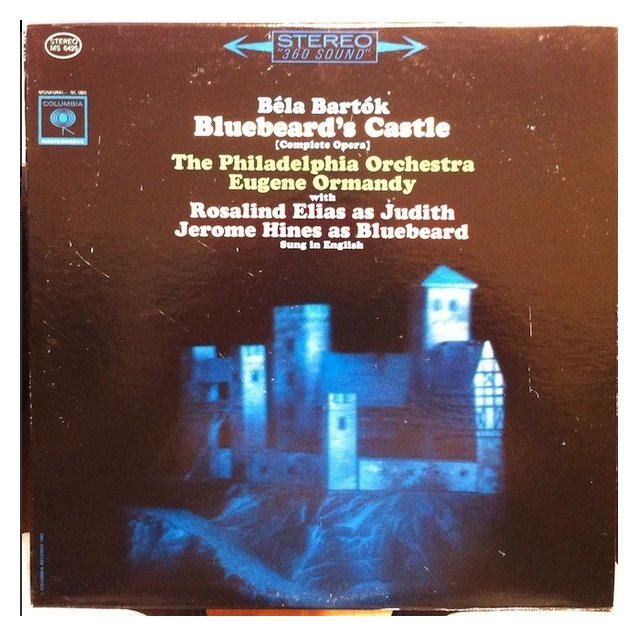

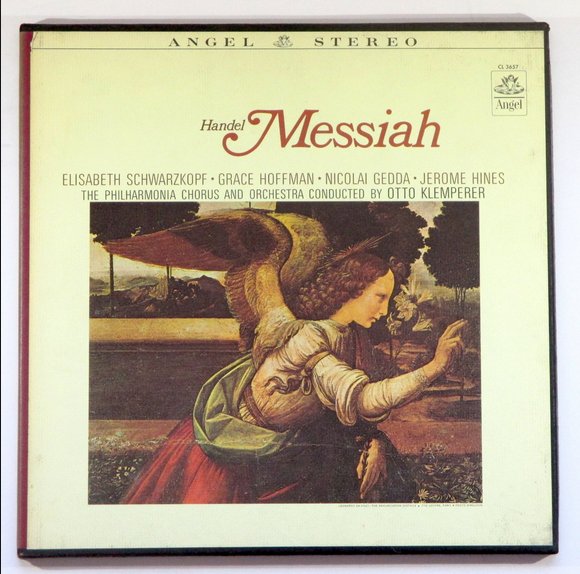

THE AMERICAN bass Jerome Hines, whose career as a singer lasted well over half a century, spent 41 of those years at the Metropolitan Opera, New York. Jerome Albert Link Heinz (Jerome Hines), singer, composer and writer: born Hollywood, California 8 November 1921; married 1952 Lucia Evangelista (died 2000; four sons); died New York 4 February 2003. The American bass Jerome Hines, whose career as a singer lasted well over half a century, spent 41 of those years at the Metropolitan Opera, New York. His enormous repertory, spanning from Handel to Britten and Stravinsky,

included Italian, German, Russian and French works. His unusual height, of

6 ft 6 in, and unusual thinness were great assets in the many roles of authority

that he sang, but were also put to wonderful use in one of his few comic

roles, Don Basilio in Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia. In his mid-thirties

Hines became a born-again Christian, and later composed an opera on the life

of Christ, I am the Way.

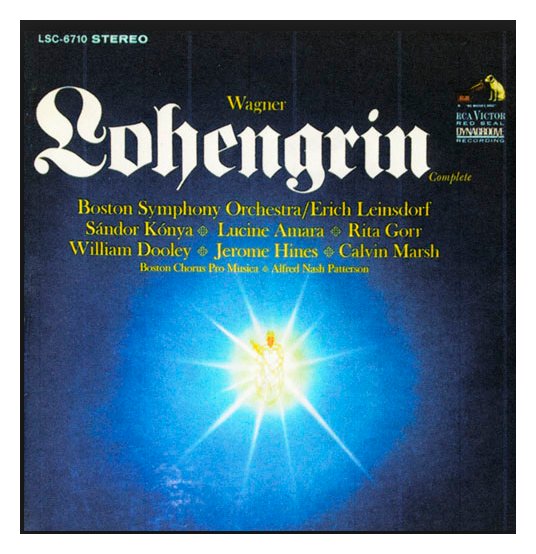

Jerome Heinz (his real name) was born in Hollywood in 1921. He studied chemistry, mathematics and physics at the University of California in Los Angeles, at the same time taking singing lessons with Gennaro Curci. He made his stage début as Bill Bobstay in HMS Pinafore at the LA Civic Light Opera in 1940. The following year he made his operatic début at San Francisco at a popular matinée performance on 19 October 1941 as Monterone in Rigoletto. The title role was sung by the great American baritone Lawrence Tibbett. Heinz also sang two performances of Biterolf in Tannhäuser, whose protagonist was sung by the even more famous Danish tenor, Lauritz Melchior. The publicity generated by this short season brought several offers

of work from concert and operatic agencies, so Hines, as he had now become,

decided to be a singer, not a chemist. From 1944 to 1946 he sang with the

New Orleans Opera, and also appeared in Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires and

Mexico City. He also sang in concerts conducted by Toscanini and with the

maestro recorded the bass solos in Beethoven's Missa solemnis. In

1946 he won the Caruso award, and made his Metropolitan début on 21

November as the Officer in Boris Godunov. Graduating shortly to Pimen

in the same opera, he finally moved on to Boris, which became his favourite

role. During the next four decades Hines sang 45 roles at the Metropolitan alone. These included Sparafucile in Rigoletto, Colline in La bohème, the High Priest Ramfis in Aida – one of his most imposing characterisations – Swallow in Peter Grimes, Banquo in Macbeth, Mephistopheles in Faust, Sarastro in The Magic Flute and two roles in Verdi's Don Carlos, King Philip II and the Grand Inquisitor. These were among his very finest roles. In 1953 Hines came to the Edinburgh Festival to sing Nick Shadow in The Rake's Progress, the British stage premiere of Stravinsky's opera, presented by Glyndebourne. The bass's long thin frame was exactly right for Shadow, while his very large, deep voice and superb diction also suited the music to perfection. The following year Hines sang Mozart's Don Giovanni, a role he also took on at the Met and in Munich. In 1958 he appeared at La Scala, Milan, in the title role of Handel's Hercules, and the same year began a five-year stint at Bayreuth, singing Gurnemanz in Parsifal. Later he sang King Marke in Tristan und Isolde and Wotan in Die Walküre. His Wagner repertory in New York also included Hunding in Die Walküre and Wotan in Das Rheingold. After his visit in 1962 to Moscow, in 1968 Hines published an autobiography,

This is My Story, This is My Song. His opera, I Am the Way,

was performed in Philadelphia in 1969. Hines himself sang the protagonist,

while his wife, the soprano Lucia Evangelista, sang Mary the Mother.

Hines gained a congenial new role at Rome in 1984, when he sang Arkel, the old, blind king in Pelléas et Mélisande. Though he retired from the Metropolitan in 1987, he continued to sing elsewhere in America, and in 1988 at Newark he sang Il Cieco, the blind father of the heroine in Mascagni's Iris. The following year he appeared as Ramfis, a role he had sung well over a hundred times, in New Orleans, 45 years after his début in the city, returning there in 1987, at the age of 76, to sing Sarastro. Elizabeth Forbes |

This interview was recorded in New York City on December 12, 1991.

Portions (along with recordings) were broadcast on WNIB in 1994 and 1996.

The transcription was made in 1994 and published in The Opera Journal in September of that

year. It was slightly re-edited and posted on this website in 2009.

More photos and links added in 2015.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.