Opera. You first think of the music and its composer. Maybe you think about the fact that it’s also dramatic, but even then one doesn’t automatically think about the words. And even when the words are important, the person who wrote those words is usually overlooked. Often that is a kindness, but more and more these days, the text of an opera is on a par with the music.

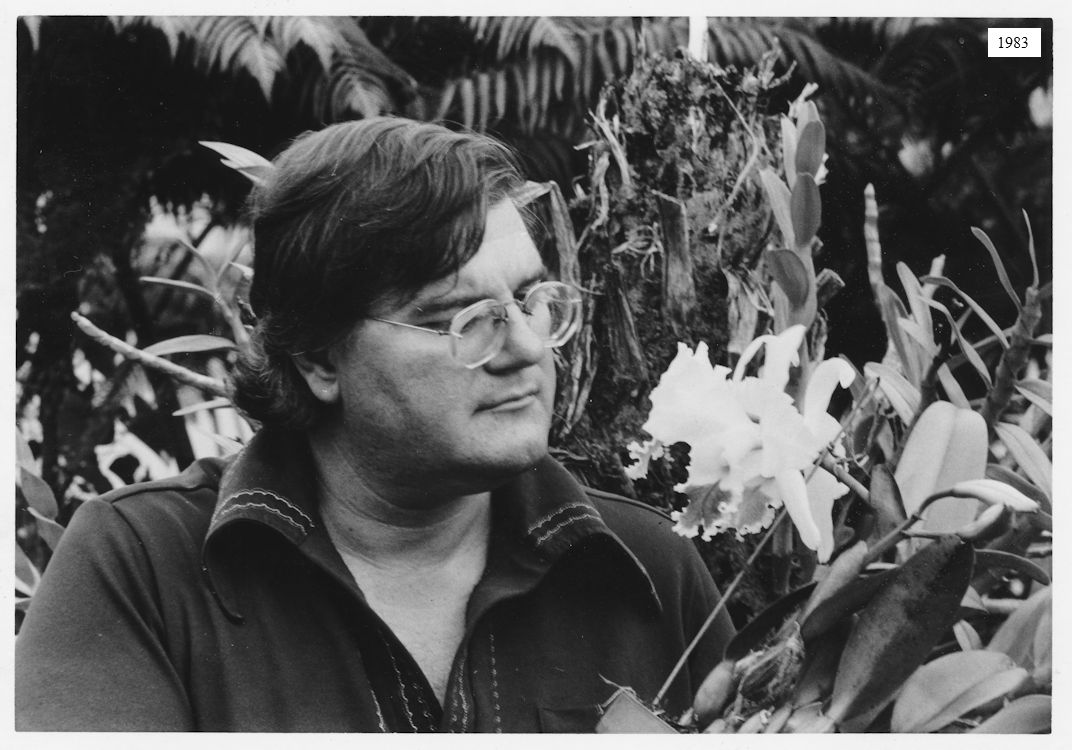

In the past, there have been a few outstanding examples of the librettist’s art: Hofmannsthal for Richard Strauss; Boito for Verdi; Scribe for Meyerbeer (and everybody else); Da Ponte for Mozart; Metastasio and Calzabigi for Gluck; even Wagner for Wagner! But these days, composers realize the importance of the text, and with greater pressure to deliver a masterpiece every time, it had better be solid both musically and textually. Harvey Hess is one of that breed who crafts words for a particular musician.

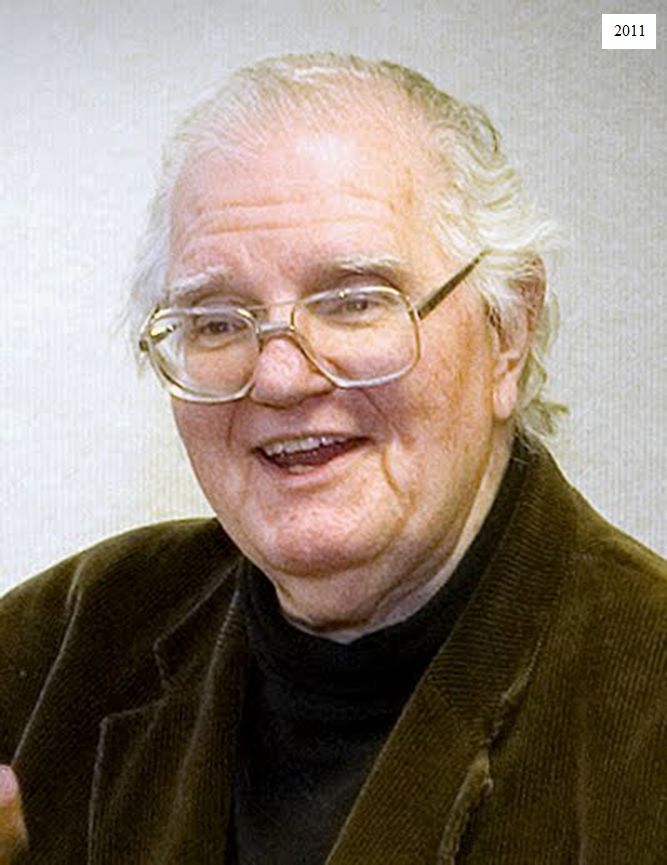

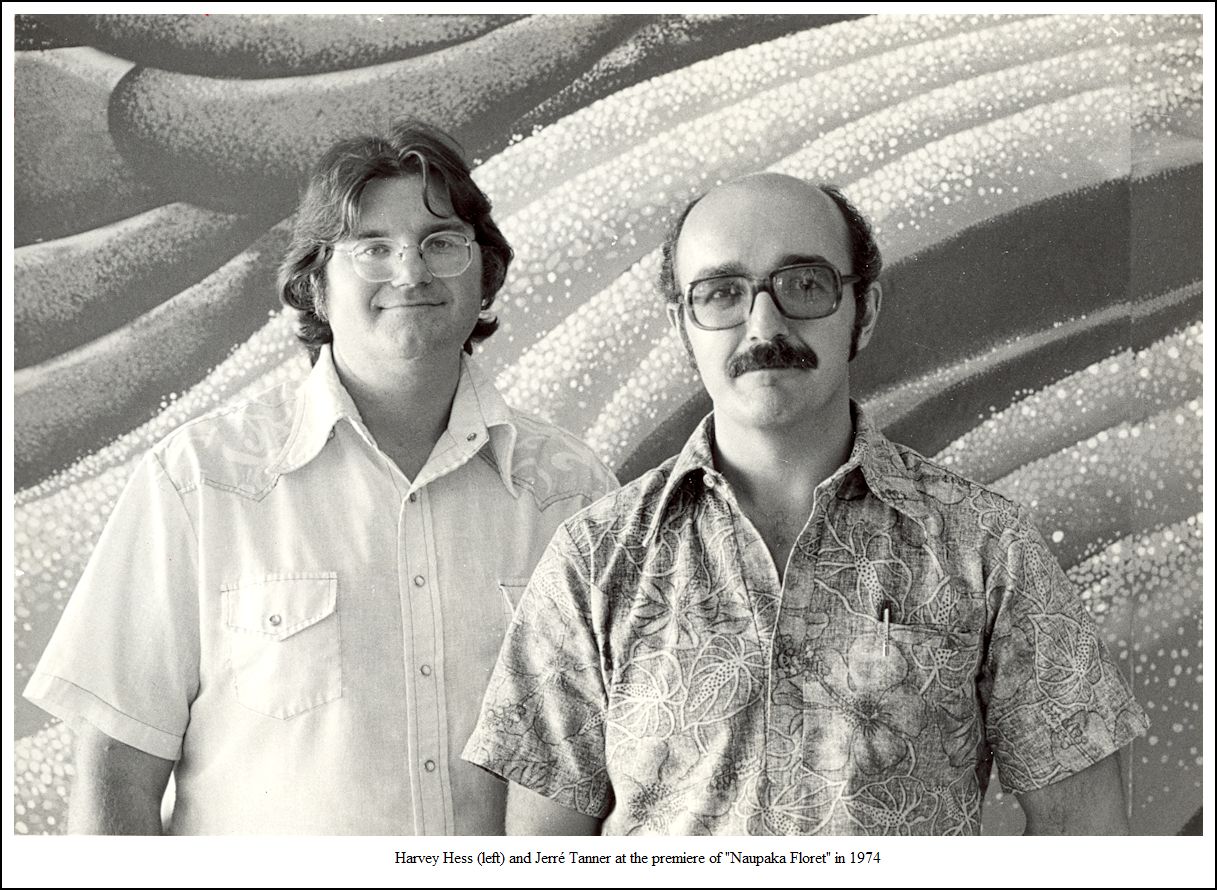

The Hawaii-based composer Jerré Tanner is emerging as a major force in music, and his operatic texts have been the result of a collaboration with his dear friend Harvey Hess. The two are originally from Iowa, and have formed a working pair-bond that has produced five operas, and is now beginning to be recognized by a wider audience. There are a few recordings on the Albany label, and another is about to go into production, conducted by Margaret Hillis.

Born just five weeks apart, Jerré and Harvey came through Chicago a few months ago [July, 1993]. Chatting with each one separately, I was aware of how much they put into each piece from their own imaginations, and yet a total working collaboration was evident.

This “Conversation Piece” is devoted to the poet.

Bruce Duffie: Why and when did you decide

to go to Hawaii?

Bruce Duffie: Why and when did you decide

to go to Hawaii?

Harvey Hess: It was principally owing to Jerré’s being there and our lifelong commitment to work together as collaborators. [Photo of the two of them is shown farther down on this webpage.] It started when we were freshmen at the University of Northern Iowa. Both of us were flute students and composers, so we agreed to bring some of our work to show each other. Mine was a very chaste motet in the Roman style with four voices, and he came in with a huge cardboard carton and said, “This is my opera! It’s Dante’s Divine Comedy.” I soon learned that I didn’t have what it took to be a composer, though I do write music criticism and played flute in the Waterloo Symphony. But when Jerré and I realized we had an artistic friendship, we made a commitment and started working together. We were both 18 years old and have never really had any break in the continuity. So, after he took his degree at San Francisco State, he went to Hawaii while I was doing other things including studying philosophy and becoming a published poet. Finally, he called and said there was such an ethos and mythos in Hawaii, he was going to stay there. So I went and stayed, also. I discovered (among other things) my desire to study things Japanese, which had begun in my teens, and also discovered for myself the wonderful universe of Polynesian mythology. I was able to write texts for song-cycles and operas. I stayed for fourteen years, and it was only because there aren’t many jobs for poets that I accepted a position as music critic with the Spokane Spokesman-Review and Chronicle. I thought that was not so very far away, and it gave me a great opportunity to meet others in the music world.

BD: Was that when Hans Moldenhauer was there?

HH: Oh yes. I would go down and see his archives, and he respected my work enough to allow me access to his source material. [Note: The Moldenhauer Archive of scores and manuscripts is now housed in the Music Library at Northwestern University.] Then, my family needed me back in Iowa. I had connections there, and an opening came up for an arts reviewer at the paper. So I returned, and since Jerré has relatives there, it all works out pretty well. We keep going by mail and telephone and fax, so there is no interruption in our collaboration. I view myself as a lyric poet who is a collaborator.

BD: Having started out in music, does that help when you’re fashioning prose and poetry for use with tonal sounds?

HH: Absolutely, especially because Jerré’s muse is brought into energy when he encounters a text that has meter and the traditional trappings of verse. It’s a very important aspect and I provide that for him. Then for myself, it’s important because I realize what the various pulses in time mean in shaping – not just little bits of meter, but how possible climaxes may be embedded in the text that will make available to the composer what he can best utilize for emotional and structural purposes. The traditional uses of verse are very much alive and available, not only through me, but through other people as well.

BD: But you have no way of knowing what muse is going to strike him for notes or orchestration for any of the texts you provide.

HH: No, that’s a mystery, but I’m always willing to revise anything so that the fluidity he needs will be available to him in the text. Someone has said that if you play “The Lord’s Prayer” on a single note, because of duration you can tell what it is that is being played. Meter is the thing I work on above all else — the placement of vowels and diphthongs. I did some singing, so I know how to get these problems out of the way And if I don’t eliminate diphthongs and swallowed l’s, the music can’t soar, nothing can arch and there’s no continuity and no climax. Jerré tells me that when an orchestral suite is played, he can hear my words, and I find that, also.

BD: Are you ever surprised by what you hear?

HH: That’s the one joy a librettist has above any artist in any art form or media because when it’s ready to be performed and all the notes are there and everyone has rehearsed and memorized the parts, the composer, the conductor, and the cast all obey what I’ve written and I just watch everything like a Roman emperor at a very great gala. Performers are just like anybody else because they’re people, but they have to continue to translate their language in a way that sculptors don’t because it’s a living thing that requires constant reinterpretation and constant response to the instrument which is a living body, which changes in time and situation.

BD: So even though they’re your same words, you expect them to be reinterpreted all the time?

HH: Absolutely I hope there is not only one unique interpretation to any work of art, be it a poetry reading or a musical performance.

BD: Well, when you’re collaborating, how much back-and-forth is there between the composer and librettist?

HH: Up until he’s committed to a set piece, it’s almost constant. Then he goes into his studio and suffers and I don’t hear from him for awhile. But we’re in touch all the time because I have a great deal of aesthetic input into the drama, the structure, the creation of scenarios, etc. It’s a hero-twin Castor and Pollux kind of thing, if I may be so bold.

BD: Do you ever give musical ideas?

BD: Do you ever give musical ideas?

HH: No, that’s totally his domain. I think that poets should learn a little humility in the face of other things that they do. The mysteries of art are such that once one has contributed something that is acceptable and the original creator can live with it — whether it’s a dance scenario or anything — I think, then, you just commit yourself to whatever may come and realize that art is great and long, and something wonderful is likely to happen if you leave things alone and simply agree with the contract within yourself to be a subordinate. The autonomy of every art in an operatic production remains perfect. The dance is the dance, and the music is the music, and the poetry — if it’s good — has real literary virtue.

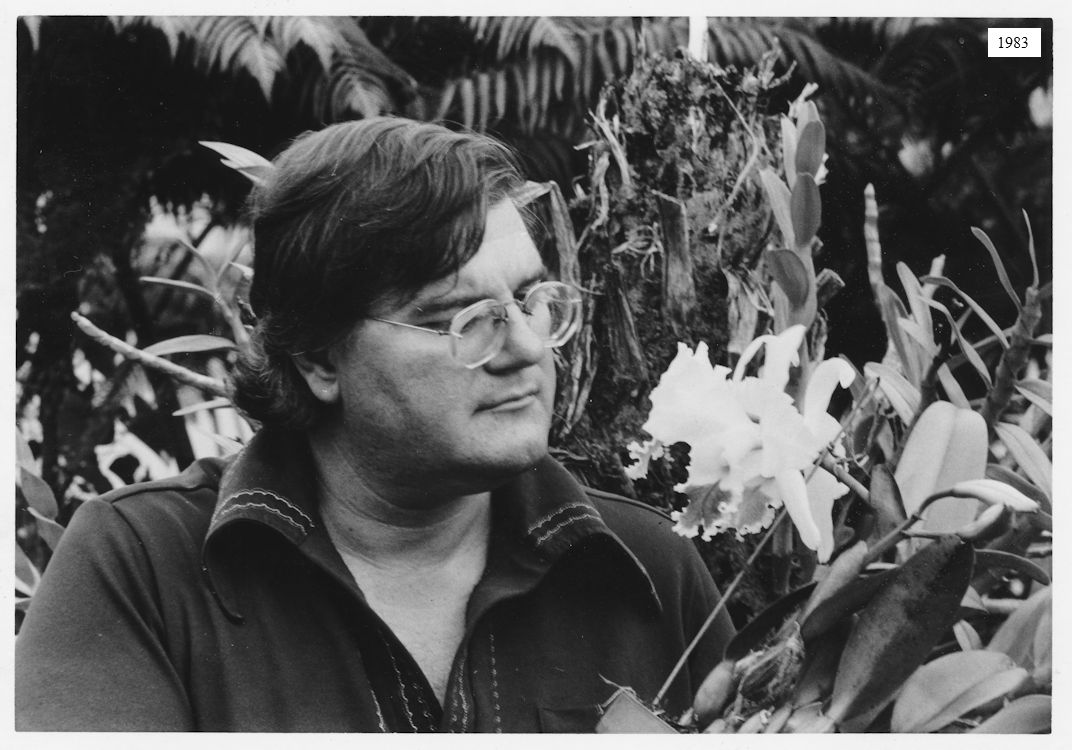

BD: You also satisfy some of your creative outlet by writing haiku and poetry not for music.

HH: Of course. If I didn’t do that, I wouldn’t be able to contribute stern enough stuff to the creative process to have any effect. Poets may be egomaniacs, but musicians and architects are megalomaniacs!

BD: So you get your own outlet in the poetry and can subordinate it when doing libretti.

HH: That’s right. [Note: The two haiku at the top of this conversation were written especially for this issue. According to Tanner, Hess was known for taking slight liberties with the number of syllables. Hess’s next book of poetry, Skipped Stones, published by Eight Pound Tiger Press in Cedar Falls, Iowa, is due out in June.]

BD: Do how do you balance those two phases of yourself?

HH: Edna St. Vincent Millay has a wonderful line: “Into the golden vessel of great song let us pour all our passions.” I think that one becomes a servant for love in the arts, and you just do it. You realize that you have this opportunity to pour nectar into this immortal vessel, and you just do it. That’s grandiose, especially for someone who writes delicate haiku, but that’s what we’re all doing. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a critic or a stagehand. We’re all pouring our lives, transmuted in song, into this vessel which has been dipped from for the service of all.

BD: So you view words as song, as opposed to music as song.

HH: Not opposed, but along with. It’s like a Chalcedonian incarnation where the two natures in Christ, divine and human, remain absolutely without change, without division, without separation, without confusion. The poetry is poetry, the music is music, but if you bring them together you have this incredible incarnation of something. Two natures in one person, and it’s like that in opera.

BD: Are there times when one of you will suggest using a text that you had written and never thought would be part of a collaborative venture?

HH: (Enthusiastically) Oh yes! This is the other thing that is a wonderful opportunity for every poet. Another person, especially one who really knows music, will see good things in what you’ve done and thought were mediocre, and with a little bit of work they blossom into something that one had never dreamed could be there. It’s something wonderful. Jerré will sometimes find dinky little things I’d done ages ago and disregarded, and express interest. Then I have to put them into shape.

BD: I was going to ask if you had to revise them for use.

HH: Unless he says no. It is the need of the music that must be answered, always. And if it’s something I’m not proud of, I think I should have gotten rid of it before he saw it.

BD: Are you the best judge of what is or is not worthy in your own works?

HH: Not always. I know technically when something is energetic and when it’s vital, but I don’t always see it unless someone else points it out. This is something wonderful about all the collaborative arts. There is another opportunity to learn and grow and alter and transform material that might have seemed dead or old and now will be given new life. One of the things needed in the twentieth century is the opportunity to look at old things anew. Working with other artists, especially musicians with poets, gives opportunity for resuscitation for material that had gotten to be lackluster.

BD: We’ve used several different words — poet, librettist, lyricist — what do you consider yourself?

HH: Since I’m a contemplative, I suppose an aesthete who writes, but a singer, too. Poetry, even haiku which is objective, must have an innate lyric cry somewhere along the way for it to be meaningful. Then I can feel it, because to be an aesthete is to feel and perceive. It’s the life of the senses.

BD: OK, then, what is the purpose of art?

HH: The purpose of art is to incarnate — in a medium which has become second-nature — in such a way that the artist is freed to embody emotion and human experience and insight, in a work that will release and express and embody those insights and feelings and experiences in such a way that you can, at last, even transcend the medium and contribute things undreamed of to its corporeality that had never been known of before – especially when one is in touch with oneself and one’s community and archetypal things such as human history and the excitement of living life in art and letting art inform life. The Japanese feel there is little distinction between the artistic life and the aesthetic life, so there is very little difference between art and life. That also happens with devout concert-goers and theater-goers. They are so in-tune with what is going on. In Hindu aesthetics, there comes a time when there is little differentiation between an appreciator and a creator. I think all artists, especially poets, need to be aware of how to appreciate what they’ve done — even the failures. Being professionally humble may be one of the most obnoxious forms of pride. That’s what I teach my humanities students – hubris is to be avoided. I love teaching because I’m able to articulate through and with my students the things that we all know and take for granted. But once one states these principles, then some of these human foibles can be expressed. Some of the students have gone through trying times and when they’re articulated, you can contemplate them and it’s no longer remote or dry-as-dust. It becomes living and interesting, and I gain from it and they gain from it, and so I find teaching is a great artistic tool for creation and contemplation.

BD: So what is your advice to someone who wants to craft libretti?

HH: Be as much of a musician as possible. The

more one knows of music, and the more one loves it and listens to

it attentively — especially Hofmannsthal

and Strauss operas — the better off

one will be. Some people disagree, but perhaps it’s because

I was a musician and it’s in my blood. I can’t imagine tackling

the task of writing words for music without knowing the technique

involved.

BD: Conversely, should composers understand the craft of writing poetry?

HH: Ah, yes! I think this is one of the reasons we have so many bland modem operas. All the corners of the respective art forms have been blunted. The poetry is sort of oatmeal and the music is sort of half and half. It should be a breakfast that is crackly crisp bacon and carefully cooked sunny-side-up eggs and freshly-squeezed orange juice. Everything should be tart and tangy...

BD: And loaded with cholesterol! (Laughter all around). Seriously, do you think there will come a time when we’ll have to have “opera lite”?

HH: That’s what our Kona Coffee Cantata is – a companion to the Bach Coffee Cantata! People should not shy away from spoken words in opera if they feel they are needed. The Schickaneder approach is great. People love to be entertained, and some of the most profound entertainment is light and great art at the same time. Whatever seems to be right in the arts should be done, however frivolous it may seem.

BD: Any advice for those singers who directly present your words?

HH: Be more conscious of those words! Live the text through your technique more incisively.

===== ===== =====

===== =====

--- --- --- --- ---

===== ===== ===== =====

=====

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on July 30, 1993. This transcription was made and published in The Opera Journal the following June. It was posted on this website in 2010. It was slightly re-edited and re-formatted, photos were added and it was re-posted on this website in 2018.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.