By Bruce Duffie

The American soprano Laura Aikin has been making a name for herself in Europe. Having sung previously with the Chicago Symphony conducted by Pierre Boulez and Daniel Barenboim, she returned to the Windy City in the fall of 1998 for her American opera debut as Zerbinetta. A few weeks later, she made her Metropolitan Opera debut as the Queen of the Night.

Originally intent on a career in Music Education, she graduated from SUNY/Buffalo (her home town) and Indiana University. Then a grant allowed two years of study in Munich, and she was a member of the Berlin German Opera for six seasons. A regular at many festivals, she now [1999] makes her home in Milan with her husband and infant son. [What follows is a more recent biography. As usual, names on this webpage refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.]

|

Laura Aikin (born in Buffalo, NY, June 20, 1964) is an American operatic coloratura soprano. She is acknowledged for her vocal range of three octaves, her acting talent and stage presence. She is also noted for her portrayal of the title character in Lulu, which has received very positive reviews in the press. She has appeared as Mozart's Queen of the Night, Zerbinetta by Richard Strauss, and in contemporary opera at international opera houses and festivals. Aikin is the daughter of a metal worker and a housewife, growing up together with four sisters in modest circumstances. At the age of 15 she experienced an opera on stage for the first time. She first studied art at the State University of New York in Buffalo, and then music at Indiana University Bloomington, as well as on a German Academic Exchange Service scholarship with Reri Grist at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater München. In 1991, Aikin made her debut at an opera gala in Berlin. From 1992 to 1998 she was a member of the ensemble of the Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin where she performed more than 300 times. Her roles there included the Queen of the Night in Mozart's Die Zauberflöte, Zerbinetta in Ariadne auf Naxos by Richard Strauss, Sophie in his Der Rosenkavalier and the title role in Alban Berg's Lulu. In 1995, she first appeared at the Vienna State Opera, as Olympia

in Offenbach's Hoffmanns Erzählungen, where she also appeared

as Zerbinetta, Sophie, Arminta in Die schweigsame Frau, the Queen

of the Night in Mozart's Die Zauberflöte, Adele in Die Fledermaus

by Johann Strauss, and Emilia Marty in Janáček's The Makropulos

Affair. Also in 1995, she performed at the Salzburg Festival in a choral

concert in the Mozarteum, and returned for many opera performances, as both

Blonde and Konstanze in Mozart's Die Entführung aus dem Serail,

the Queen of the Night, Badi'at in the world premiere of Henze's L'Upupa und

der Triumph der Sohnesliebe, Marilyn in Robin de Raaff's Waiting for

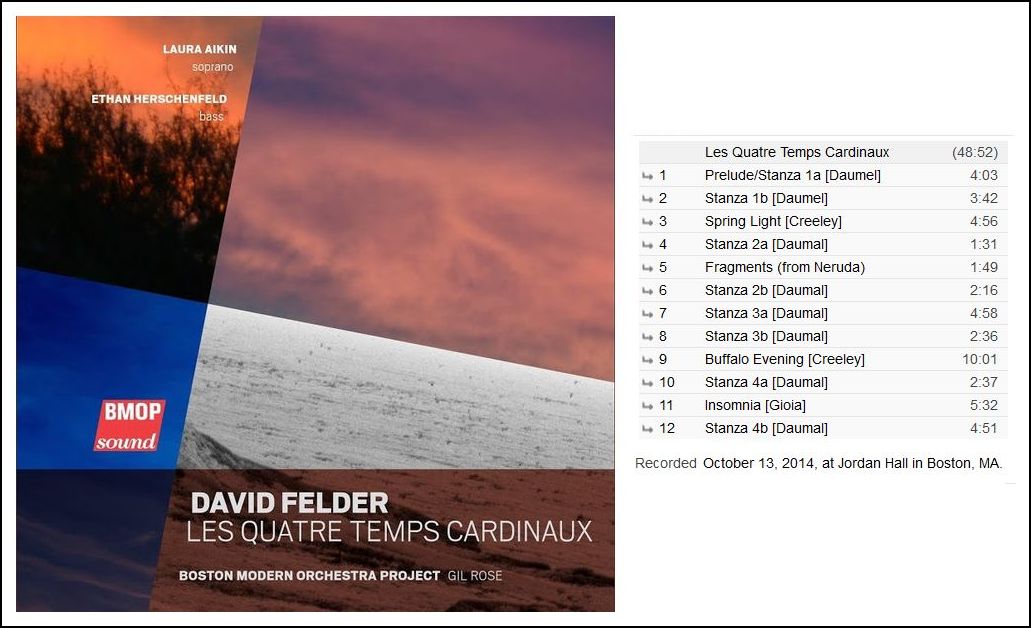

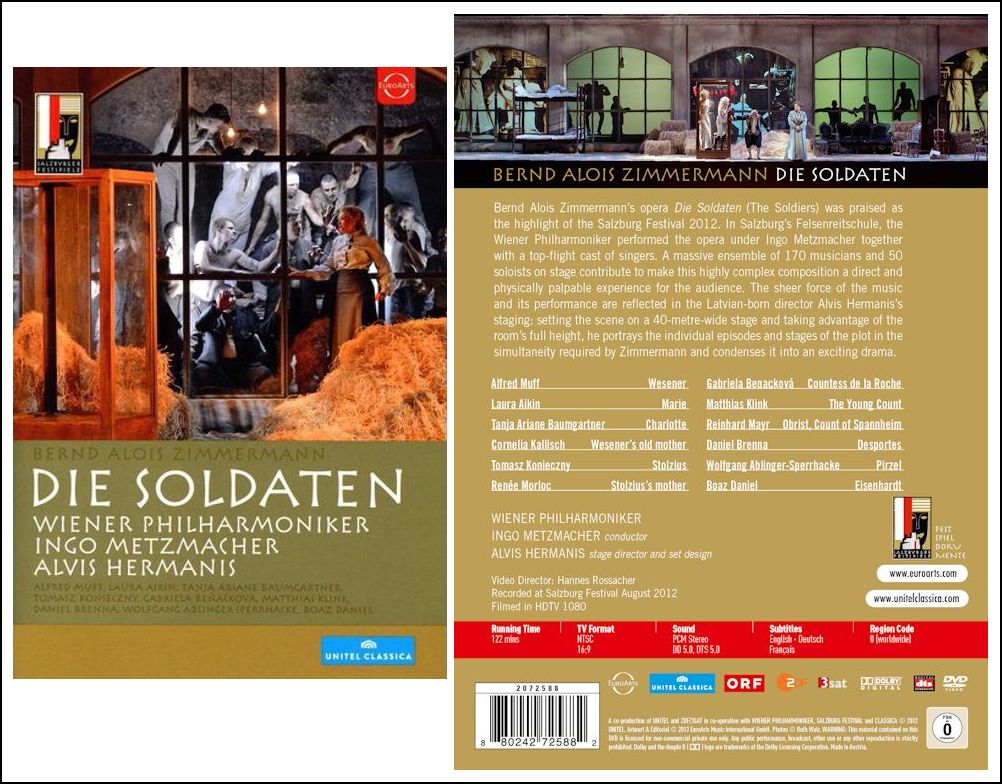

Miss Monroe [recording shown below], Marie in Bernd Alois Zimmermann's

Die Soldaten and in Birtwistle's

Gawain.

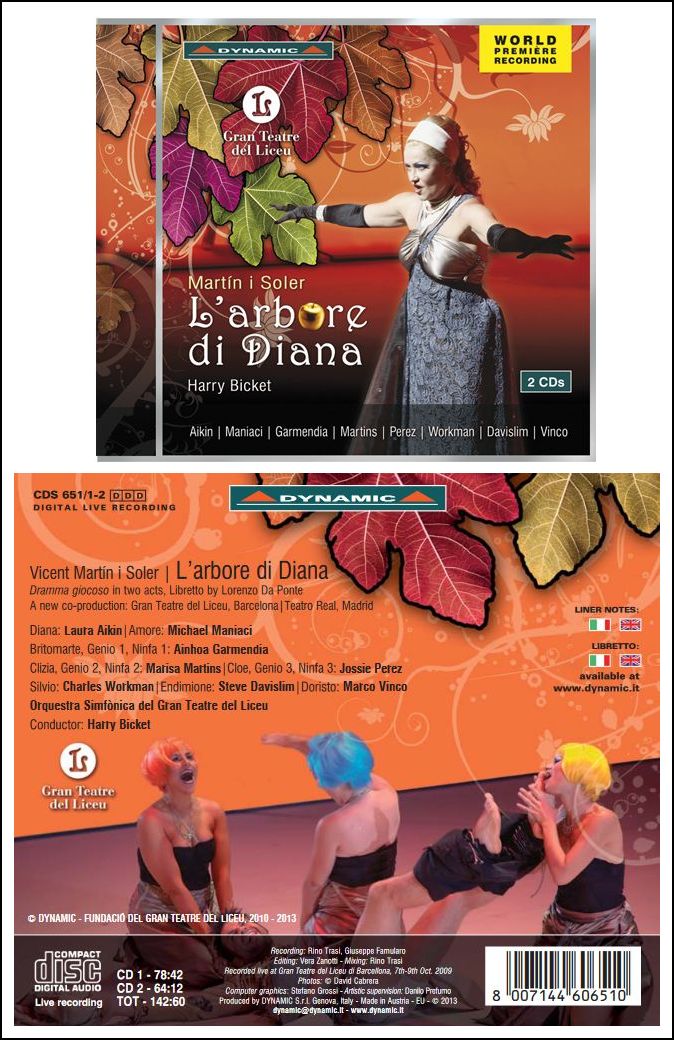

Aikin has appeared as a guest at major European opera houses, including the Dutch National Opera, La Monnaie in Brussels, Opéra Bastille in Paris, Opéra de Lyon, Semperoper in Dresden, Oper Frankfurt, Bavarian State Opera in Munich, Opernhaus Zürich, at the festival Maggio Musicale in Florence, Teatro San Carlo in Naples and at the Liceu in Barcelona. In the United States, she first appeared at the Met as the Queen of the Night in 1998/99. She took part in the world premiere of Salvatore Sciarrino's Ti vedo, ti sento, mi perdo at La Scala in Milan, in the role of the Sängerin. The opera was co-produced with the Staatsoper Berlin, where it was first performed in July 2018. |

It was while she was in Chicago for the new production of Ariadne that I had a chance to chat with

this funny and engaging coloratura. Knowing that her big aria always

results in wild applause just before the musical ending, I began with

that question . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Does it bother you knowing people are going to applaud too early?

Laura Aikin: No. [Laughs] Not at all. I'm used to it. I sort of depend on it. I'm sure that it happens almost every production.

BD: Do you like playing Zerbinetta?

Aikin: Very much. It's a very nice role with lots of time to play. There's a little bit of drama in the beginning so you can show your stage chops, your acting chops, but it's an awful lot of fun. Of course, working with the guys is always a riot with the dancing and the flirting and just what we're doing on stage is exactly what the rehearsals are like. We're just having a good time. None of us are dancers, of course, and so there's always a moment when somebody's frustrated and so it's very nice when all five of us have got it figured out at the same time near the end of the rehearsals when things are set and then we can just sit down and stand up and enjoy ourselves.

BD: Do you usually play happy roles or are you also playing some sad roles too?

Aikin: I've played some really tragic roles. Rosenkavalier can be very depressed actually. Sophie has a lot going on, like Lulu.

BD: Lulu's not happy, no.

Aikin: She's got some happy moments though. She thinks she's happy anyway. [Laughs] Also, I've done Amenaide in Tancredi. She's got some extraordinarily dramatic moments.

BD: Does it do your heart good to know that you're going to be pawed-over by several guys in Lulu?

Aikin: Oh sure. I like operas where I'm the only girl. [Both laugh] They're a lot of fun.

BD: In Rosenkavalier, it's two girls and a girl playing a guy. Is it difficult playing against a guy who's really a girl underneath?

Aikin: No, no. It depends on how mushy and smushy it gets, and how many kisses there are. One becomes more concerned if it's going to make the audience feel uncomfortable. I did one production of Rosenkavalier where the director had it very sexual, and there was quite a bit of heavy kissing going on. Some of the audience members could then really forget that it was two women. Other times, it just depends on your level of maturity to be able to handle something like that. But it's certainly not a problem amongst the colleagues. We're all aware that this is usually what happens. It's just simply necessary in these roles because they're young men, and they have to have this innocence about them. Having it sung, then, by this voice type – this mezzo soprano – makes it all that more vulnerable of a character.

BD: Of course, being a young man, the character is a little awkward, and being a woman playing this role is slightly awkward. Does that put the right amount of awkwardness in it?

Aikin: Maybe in the beginning, but it settles down after you've done a couple of productions. You get an idea of how to do that and sell it correctly. In the beginning, you ask yourself, "How do I walk like a guy?" But most mezzos are accustomed to playing a man and they can put themselves in that role and not feel uncomfortable in it.

BD: Do you ever find yourself playing a little extra feminine off of that, or do you just try be yourself?

Aikin: A couple of years ago I was pretty wild. [Laughs] Now I'm a married woman and very calm and stale. My husband wouldn't agree with that, but I think Zerbinetta is just a girl having a nice time and enjoying her youth and enjoying the attention she gets. My favorite part of her is this very theatrically savvy person who knows how to make the show go on and make it work and inspire her colleagues. I like that. I like to think of myself as being a person like that. She's the one who brings some energy to a production, not just to my own performance. I like that in Zerbinetta because I get the chance to do that on a stage, and off a stage. I've been accused of being a cheerleader for many productions that I'm in.

BD: You're supposed to be!

Aikin: Yes, unless I'm doing something serious. My biggest kick was when I did Lulu because I had so much responsibility and every single person in the show was dependent upon me. I'm the whole show, and everybody is basically doing duets with Lulu throughout the whole thing. I love this responsibility and having people depend on me and being able to help them. It was one of the most wonderful aspects about doing that role actually.

BD: I assume you only do the three-act version.

Aikin: Yes.

BD: Then, of course, you get it on

with Countess Geshwitz so there you are, back again with another woman

onstage.

BD: Then, of course, you get it on

with Countess Geshwitz so there you are, back again with another woman

onstage.

Aikin: Yes. Exactly. That relationship is much more intense than the Composer or even Octavian because that's a woman playing a lesbian. The whole sexual tension there is much stronger. It's not this innocent sort of thing. This is a woman who knows about sex with a woman. It's not a boy having his first kiss. Of course, Octavian knows something about sex too, but he's experiencing it another way when he does it with Sophie than he does with Marschallin of course.

BD: Is Sophie his second playmate?

Aikin: Definitely at least his second. I would say maybe even a few more. I would put her up the list. I wouldn't say too many. You probably can count it on one hand. But I would say he's probably had a little bit other experience... a couple of tumbles in the hay with a couple of maids or something like that.

BD: Are Sophie and Octavian happy in the 'fourth act'?

Aikin: I think there's a transition for both of them, and assuming the families are happy with the situation, it would be a very good marriage actually. He will have then gotten the experience he needs to get into a marriage. Of course, how does one define marriage in those days anyway? They weren't meant to be faithful to one another for very long in any case. But, I think that they click. It's very clear musically that they click. It's nice then when scenically it clicks too. I think that it bodes well for the relationship in the future.

BD: How much does Sophie then mature at the end of the third act?

Aikin: In the production I talked about where there was a lot of kissing, Sophie was actually quite sexually aware. She knew what was going on. She had had her little fantasies, and she actually knew about Octavian and had fantasized specifically about him. So she was ready for this sort of thing. She was in the convent, but was a bit of a rebel.

BD: Is that why she had been sent to the convent?

Aikin: No, I wouldn't say that because she had been in the convent her whole life. She hadn't reached that point yet. But when she came out, she probably gave the nuns a run for their money. That's my kind of Sophie. I like doing that. Also, the relationship with her father was very awkward in this production.

BD: Why?

Aikin: Because she didn't know him. He was basically a stranger to her. Her mother died very young, and the father did not know what to do with this child. So he just sent her away. Maybe saw her once a year, and when she was home, he was very distant, completely unaware that she was even there. He was always busy with his business, business, business, because he is, of course, a businessman. So, Sophie shows up and he's just thinking about selling her. It's probably something he's been thinking her whole life. This is something he will certainly sell someday. If he didn't get the son that he always wanted, at least he'll be able to sell the daughter and get himself a title for it.

BD: So he's looking for personal gain rather than making sure Sophie's happy?

Aikin: Yes, absolutely. He doesn't care one bit about her happiness. Otherwise, I don't think he would have matched her up with a man like Ochs. Her father certainly must be aware of the kind of reputation that this man had, despite the title. He could have maybe looked a little harder. He could have gone one level lower and looked a little harder. The father figure in Rosenkavalier is a very negative, very selfish man.

BD: Does that make you, as Sophie, want to do something different in your own marriage with Octavian?

Aikin: She would like to have a good marriage with Octavian, and she probably would want to be a woman who is there for her children. Of course, her mother died, so you can't quite blame the woman for not having raised Sophie the right way and taken more care with her. The production I did in Berlin was very interesting, because Sophie normally has a big wedding dress, or is complete and all pretty for the second act. Instead, I was still wearing my convent dress with the concept being that they had basically not really gotten to that point yet. They hadn't really thought about it. They were all worried about themselves, and had forgotten to dress Sophie up. It was like she was nonexistent, with everyone looking past her pretending she didn't exist, and no one really cared what she thought or did.

BD: So making the sale was more important than the human commodity?

Aikin: Exactly. It didn't matter to Ochs what she looked like anyway. He says, "She's kind of skinny, but it doesn't matter. We'll fatten her up." You know he doesn't care. He's buying a young sheep. He can make her fat, or he can make her thin. He's just going to do whatever he wants to do with her.

BD: So she's just going to be the official mother of his kids and he'll have other kids elsewhere...

Aikin: Yes. He already has lots of kids. He's just looking at her for the money to support his title, and the father of Sophie is looking for the title to support his money. So it all has nothing to do with Sophie as a person.

BD: Do you want to slap them both around?

Aikin: Oh yes, I do. [Both laugh]

BD: Could a stage director get too moralistic about that?

Aikin: No, I don't think so. There's certainly a lot of room to do something with that. Strauss can be really boring if everybody's just standing around singing, because there are moments when it goes on and on and on and on. So any color that one can bring to it will certainly help make the evening a little shorter for the audience. All these white wigs and longing looks get old after a couple of minutes. But Strauss knew what he was doing when he was creating these characters with their positive and negative sides. I think he would have liked it if they had a little bit of bite to them.

BD: So you be sure that you bring bite to it?

Aikin: I try to. I don't see any point in doing opera if you're not bringing bite to it. Otherwise, it's kind of silly.

BD: What's the point of doing opera?

Aikin: Coming from a background of musical theater, I went into opera because I found that it took the expressions of the characters and of the drama one step further, because the music was so much more complicated, more intense and more expressive. So, the productions themselves tend to be more complicated. I love when a production has a bit of a modern twist to it, and it's got something that says something to the eye. I like productions that are not conventional. You don't have to have people painted blue or floating around or things like that, but something should make it new. I don't necessarily agree with taking a production and putting in a different time, because that causes so many anachronisms. But making a modern painting out of a production can be very effective in creating emotions within the audience. It's better for the audience if they see it as a dramatic experience. It's important that the audience feels that they can get involved as much as they would get involved in going to the cinema.

BD: [With a wink] It ain't just

a concert?

BD: [With a wink] It ain't just

a concert?

Aikin: [Laughs] No. It ain't just a concert! Something else that helps is the surtitles. The audience has instant understanding of what's happening on the stage. Their use is an art, and the people who run the machines and do the translations have a very difficult job. It takes a lot of study of the drama, and a complete understanding of staging. People who are on the surtitles should attend quite a number of the staging rehearsals so they know when the punchlines hit, and when they're going to ruin the punchlines by projecting the joke too soon.

BD: Let me ask the "Capriccio" question. In opera, how much is the music, and how much is the drama?

Aikin: That depends on the scene. It changes from one scene to the next. There are moments when the music is expressing something far beyond what the words can. It is just like when you are in a situation and words fail you, but the emotions are bubbling out. In the same way, there are times when you can be very cool, and express something with words very clearly without getting emotionally involved. There, the music expresses the emotion and the text expresses the thoughts. So it's going to depend on the moment in the opera which is more important. Certain arias, of course, tend to have less text, so that they can be more developed emotionally through the music, whereas the recitatives are just quickly spoken. It's not just to move the pace along, but it's also a moment that perhaps emotions are not quite as strong. Then comes Zerbinetta's aria when God knows what that's all about. [Both laugh]

BD: Is it fun to sing?

Aikin: It's getting to be fun. I've now done it thirty times, and the last few times I really feel like I've gotten into it, and I can do a certain out-of-body experience with it. I'm not inside myself constantly thinking technically about what I've got to do with my body. Now I can just relax and just sing it, and know it's always going to be there. I feel very comfortable with it, and I can play with the audience more. There were times that I was acting, and playing with audience, and suddenly, "Oh my God, I've got to sing this aria." It's a difficult aria, you know. It's probably the most difficult aria ever written in opera, and it comes between two quintets where you tend to be jumping around a lot.

BD: So you're out of breath?

Aikin: Yes, you tend to be out of breath sometimes, and the stage directors usually want quite a bit of movement in the aria. In this production, John Cox was very conservative in his staging. I showed up and he said, "Okay, let's do the aria." I asked him, "What are the props? What's the concept? Where's the slide? Where's the cartwheel where one of the guys throws me around?" But there was nothing. I've got the rock, and that's it, and we've already used the rock. [Laughs] Okay... now what do we do with the rock? So, it was quite a challenging thing. But it actually made me look at the aria more intensely with regard to the text, and really approaching the audience and trying to explain something to them and to Ariadne. It made the context all the more strong, because I was not concentrating on whether I could do that cartwheel while I was singing a high E. I've done some wonderful things in that aria, wonderful stagings that I just love. Once, we were on a beach and I did a strip tease down to a bathing suit. I was wearing suntan lotion, and we used our shoes as telephones. We were tossing shoes around, and big beach balls, and umbrellas and lots of fun things.

BD: And you still managed to get through all the notes properly?

Aikin: Yes, but I was worried a lot about the beach ball. Now I have no beach ball. I just sing the notes, and it's been quite an eye-opening experience actually. I enjoyed it. At first, I was somewhat concerned that I was not doing anything. Everything that I'm doing in the aria I forced him to let me do, like walking along the footlights. He was against that for a long time, and I said that I've got to do something! I had to show some kind of danger. At some point there had to be something dangerous, because she's the person that lives on the edge. In the aria, which is basically her credo, if there's no moment of danger, you miss the heart of Zerbinetta. So we came up with this idea of her walking along these candle footlights, and letting the others onstage wonder whether she's going to go up in flames or not. That was kind of fun.

BD: I liked that the stage manager comes out with the fire bucket!

Aikin: I'm really doing a balancing act. It's only maybe six inches wide. I'm singing all this coloratura walking along the front of the stage, and there were times when I fell. I didn't fall in the performance, but in the rehearsals I was almost losing it. At the dress rehearsal I had a real tumble and fell forward.

BD: You're working without a net.

Aikin: Absolutely. Always. I wouldn't even consider a net.

BD: Is that what Zerbinetta does, work

without a net?

BD: Is that what Zerbinetta does, work

without a net?

Aikin: Always. That's what Laura does!

BD: How much is Laura and how much is Zerbinetta?

Aikin: I guess there's a lot of me in this role, especially when I was younger, in my wild days... I really respect the theatrical side of her, and that is something I try to bring into my own work – the idea of professionality and flexibility, and just not taking it all so gosh darn seriously. Basically, we're all clowns. We're just out there to entertain. There are moments when certainly this job has a higher significance historically and culturally, but the vast majority of it is that we're really out there just to entertain, and to give people a good show, and the more energy you put into it, the more love you put into it, the better. There's just no place for the ‘diva scenes'.

BD: Is that what you try to convey to the Composer in the Prologue?

Aikin: Yes. "Just calm down. Just relax. It's not so bad. Other composers have sold their works, and sold the souls of their works for much less. Don't worry. You'll survive this."

BD: Does the composer survive for a next opera?

Aikin: Yes. I'm sure he gets another playing of Ariadne if he can do it the way he wants. This happens in theater all the time. Somebody comes up with a bonehead idea, and you've got to go with it.

BD: Another one of my favorite balance questions. In opera, how much is art and how much is entertainment and where is that balance?

Aikin: Hmmm. It depends on the moment. When you are involved in a new opera, it's art and it's history. It also depends on the production. If the production is saying something new, then it's more art than entertainment. If it's a production that, shall we say, is a conventional sort in its tenth performance, then you are getting more entertainment. The quality of singing, of course, must be very high. I personally believe that these roles are now being sung better than they were when they were first written. We're getting more of a handle on them now, and have learned how to do them technically. Also, the orchestras are now more under control. That's a very important thing. Ariadne's orchestra isn't that large, but I'm referring to Lulu, or any opera that has a huge orchestra. That has more to do with color than volume, and now we're able to give them a more accurate playing than they even had when their composers were present. I have a very good relationship with Pierre Boulez. I've talked to him about this quite a bit, and he agrees with me in that respect. He says when Pli selon pli was written, it was considered unsingable. Now, it's a piece of cake. [Laughs] It takes a couple of hours to work on, but in that respect maybe we're serving art quite well now.

BD: Of course, you're talking about the performance-end. Have we made the connection now with the audience in works like Lulu and Pli selon pli?

Aikin: That's a good point. We always have to be responsible and aware of the fact that the audience is new every night. That's actually something which is easy to forget. You just think that it's the same people every night, and they'll know that you're singing it better tonight than you did last time. We do have a certain responsibility to each audience to present something fresh, and with a full heart and with full attention.

BD: Is there anything you can do as performer of new music to help bridge this gulf between the performers who understand these new pieces, and the audience that may or may not be resisting anything that's not tonal?

Aikin: The most important thing is to sing the pieces accurately, and with a good tone. Just because it's difficult, you can't scream it or fail to sing it accurately. These composers are geniuses. It's undeniable. Otherwise, we wouldn't still be doing their works, and we need to take them very seriously. When one takes the time to learn the music well, and learn it correctly, it becomes, for the most part, very good for the voice to sing. It is not necessary that modern music is going to ruin your voice. If the piece itself holds together, then you're more confident when you're on stage, and you can open up to the audience more. When I tend to do modern music, I try to put a little bit of drama in it – even to what gown I select to wear. I put as much effort into my presentation of a modern piece as I would in any piece I present to an audience.

BD: From all of this old music and new music, how do you decide what you're going to sing and work on, and what you're going to set aside and not bother with?

Aikin: That has a lot to do with my plan at the time, how much time I have to prepare it, and what I'm doing before and where I'm going to be. You're always saying at the last minute, "Oh, I've only got three weeks to learn this!" I just recently turned down something that I would have done in January because the piece that I'm doing before it is completely different. I couldn't be doing one thing after preparing another, so I just had to turn it down, although it was a piece I would have liked to do very much. It will come up again. It always does. I still have a couple of years in my career. [Laughs]

BD: Are you looking for the long career?

Aikin: Of course. That is actually why I like modern music, because I'll always have something to do. I'm very good at learning modern music. I've got a brain for it, and I've got an ear for it. I have no problem. I don't have perfect pitch, but once I get something in my ear, it stays really well.

BD: Do you have a heart for it?

Aikin: I have respect for it, and for much of it I have a heart as well. Some of it isn't very heartfelt, and the best one can do is have respect for it.

BD: Have you done some world premieres?

Aikin: I've done a lot of modern

things in Germany, often a "Berlin Premiere" or "German Premiere." I'm

doing a new production of Alice in Wonderland by a Russian composer

in Amsterdam in 2001. That was a funny thing. They wanted to

talk to me for years about Alice, and when the composer finished the work,

it turns out that Alice was a child's role written for a little girl to

speak. I was disappointed because I thought Alice would be an awful

lot of fun to do – sort of like Gretel on drugs. [Laughs] I

was very excited about that, but now I'm doing the White Queen, and he wrote

a coloratura part for me. I've only turned down things that I think

that the composer didn't know really what he was doing. I've even

turned down very famous composers' works. I've said to composers right

to their face, "You would never tell a flutist to play a run, and then pick

up his flute and bang it in on the music stand, and then start playing again.

If you want me to sing this phrase, you had better believe me that it is

bad for the human voice. So, if you want this work to get performed

in the future, this is a problem. If you want top-class singers to

sing your works, you've got to do things that they can sing, and not be totally

fried when they go and sing some Mozart." These composers often think

that singers are lazy and stupid. I've spoken to a lot of composers,

and they do think that singers don't want to put the effort into it. It's

a two-way street. They have to respect us as they would expect to be

respected by us.

Aikin: I've done a lot of modern

things in Germany, often a "Berlin Premiere" or "German Premiere." I'm

doing a new production of Alice in Wonderland by a Russian composer

in Amsterdam in 2001. That was a funny thing. They wanted to

talk to me for years about Alice, and when the composer finished the work,

it turns out that Alice was a child's role written for a little girl to

speak. I was disappointed because I thought Alice would be an awful

lot of fun to do – sort of like Gretel on drugs. [Laughs] I

was very excited about that, but now I'm doing the White Queen, and he wrote

a coloratura part for me. I've only turned down things that I think

that the composer didn't know really what he was doing. I've even

turned down very famous composers' works. I've said to composers right

to their face, "You would never tell a flutist to play a run, and then pick

up his flute and bang it in on the music stand, and then start playing again.

If you want me to sing this phrase, you had better believe me that it is

bad for the human voice. So, if you want this work to get performed

in the future, this is a problem. If you want top-class singers to

sing your works, you've got to do things that they can sing, and not be totally

fried when they go and sing some Mozart." These composers often think

that singers are lazy and stupid. I've spoken to a lot of composers,

and they do think that singers don't want to put the effort into it. It's

a two-way street. They have to respect us as they would expect to be

respected by us.

BD: That's good advice for the composers. What advice do you have for other singers who want to do modern music, or who are perhaps getting sucked into modern music unwillingly?

Aikin: Sing it with a beautiful voice. Sing it well, and then people will hear you singing something modern and say, "That's a voice which could also sing Mozart." They won't say, "That's just a modern-music singer." Very often, modern-music singers get pulled into doing something strange, and it's very effective, but the human voice is not meant to do that. Otherwise, we would have been doing that for a hundred years. One can do it for an effect occasionally, but one can't maintain that for very long without tiring the voice. Singing should never be a tiring experience. It can be invigorating. It can need a lot of muscular activity, but you shouldn't leave the stage thinking you can't talk anymore. I've done Lulu, which is four hours of opera, and I was only off the stage for twenty minutes. I was onstage the whole time, and at the end of the night I felt fresh as a flower. I wouldn't have been able to do it again that night, but I was completely fresh because I sang the notes as they were written.

BD: So Berg really did understand the voice?

Aikin: Yes, very well. There's some really wonderful vocal writing in that piece. He also orchestrated it well, because he didn't really want a dramatic voice for the role. He wanted a coloratura. Otherwise, he wouldn't have written high F's and high E's. The role sits very, very high. Although it has a huge orchestra, most of the time, when Lulu is having a lot of emotional outbursts, the voice cuts through very well. The moments when it's in the middle of the voice, the orchestra gets very thin, and very funky, and ethereal, and the colors are very well balanced. It's a supremely singable opera.

BD: Are you optimistic about the whole future of opera, and music in general?

Aikin: If we support our composers, yes. I give my greatest praise to any composer who has the tenacity and the courage to actually write a full-length opera. Today, with the density of the compositional techniques, it's hard to put down on paper a three-hour piece. It's very easy to come up with a twenty-minute piece for this and that, or even a symphony of forty-five minutes or so. But to really do an opera and come up with the right librettist, it's quite the challenge. I really take my hat off to the Lyric Opera of Chicago. They support their artists and their composers.

BD: Are you at the point in your career that you want to be now?

Aikin: Yes! I'm farther along than I thought I'd be. I'm very happy. My career isn't the biggest in the world, but I have a very intact family life. I consciously put the breaks on my career to allow the man that I have chosen to be my life's partner to catch up and understand what it was all about. Now he is as passionate about my career and our family life as I am. We have a wonderful partnership. The years that I spent "Fest" in Berlin were to develop my craft, to get tough, and to develop language skills. I worked very hard when I was in Berlin. They used me. That was one of the things. They used me as much as I was able to be used. I can't say that I was abused by them, but I was definitely used very much.

BD: But you used it for experience.

Aikin: Right. I used it for experience.

Even though I sang Matrimonio Segreto

God knows how many times, or Queen of the Night, or even Rosenkavalier, the repetition of the

productions and the performance gave them such a depth to my understanding

of the roles. I feel very confident about my languages. Of course,

nothing's perfect, and I'm always working. But I'm very confident of

my ability to take staging ideas, and to work with a conductor.

BD: I assume singing here at Lyric is a big thrill for you.

Aikin: For me, it's actually more of a thrill

because it's a new production. New productions nowadays are so few

and far between with the co-production concept now. To actually do

a brand-new production is so rare, and to have it be Ariadne here in Chicago was a dream come

true. I found out about this production two weeks before I had

my son, when I was in a state of, "What am I doing with my life? I'm

having a baby! My career's over!" Then the phone rang with

this offer from Lyric. Oh cool. Okay, fine. Life's

good. Fine, fine, fine. All right, I can handle this.

BD: Thank you for spending this time with me today.

I wish you lots of continued success.

Aikin: I will always do my best. Thank you.

* * *

* * *

Bruce Duffie is in his twenty-fourth year at WNIB, classical 97 in Chicago,

where his interviews with singers, conductors, composers, etc., are aired

regularly. Next time in these pages, a chat with bass Mark S. Doss, who

created the central role of Cinque in Amistad by Anthony Davis.

========

======== ========

-------- -------- --------

======== ========

========

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 9, 1998. It was transcribed and posted as part of my series in The Opera Journal in March, 1999. It was slightly re-edited, and the photos and links were added in May, 2023.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.