[Note: This conversation took place in May of 1982 and was

published in Nit & Wit

Magazine in January of 1986]

TWO

BENJAMINS:

LUXON TALKS ABOUT BRITTEN

By Bruce Duffie

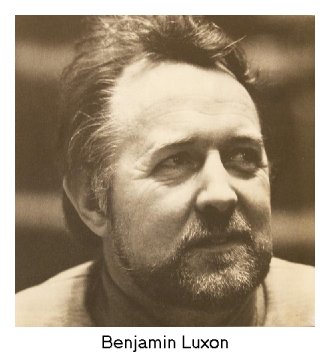

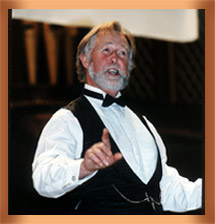

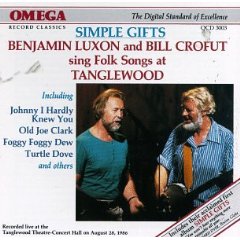

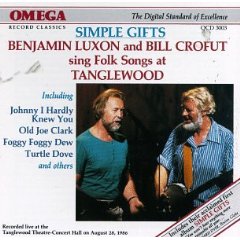

Benjamin Luxon

is a fine English baritone who will be in Chicago in mid-February

[1986] for performances with the Chicago Symphony of the War Requiem by Benjamin Britten.

His repertoire encompasses many roles – including that of Eugene

Onegin, which he has sung at Covent Garden, the Metropolitan Opera, the

Boston Symphony, and at Ravinia in 1980. He has also appeared as

Mozart’s Don Giovanni, and in operas by composers as diverse as

Monteverdi, Janacek, and Peter Maxwell Davies. He has given

concerts of Schubert and Wolf, and is closely identified with the music

of Benjamin Britten.

Mr. Luxon is represented on recordings not only

in operas of Britten, but also music by other English composers

including Bush, Delius, Elgar, Handel, Vaughan Williams, and Walton,

plus two delightful discs of Victorians duets with tenor Robert

Tear. He is soloist in music of Schutz, Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and

Beethoven, and has recorded songs of Modest Mussorgsky.

The New Grove says of Benjamin Luxon, “He uses

his warm, sympathetic baritone with commendable artistry to evoke

character; and on the concert platform his histrionic powers are

sensibly modified by an extra care for line and words.” No small

praise from the foremost English-language musical encyclopedia.

Chicago has seen several of the major works of

Britten – Lyric Opera has given Peter

Grimes in two seasons, and their school has produced both The Turn of the Screw, and The Rape of Lucretia. The

Chicago Opera Theater has presented Albert

Herring, and now the Chicago Symphony will give the War Requiem. Recently, it was

my good fortune to have the opportunity to chat with Mr. Luxon.

We had only a limited amount of time, so our conversation centered

around the music of Britten. Here is much of what we discussed…..

Bruce Duffie: Let me start out

by asking you about Benjamin Britten. You’ve done quite a bit of

work with his operas, so how are they different from operas by other

contemporary composers?

Bruce Duffie: Let me start out

by asking you about Benjamin Britten. You’ve done quite a bit of

work with his operas, so how are they different from operas by other

contemporary composers?

Benjamin Luxon: That’s an

opening question isn’t it! First off, he wrote more operas than

most other contemporary composers, and there was the interesting thing

that he was always interested in small forces. He was interested

in exploiting and getting maximum results from very small forces, so

you have all the chamber operas.

BD: Was this because he

thought he’d get more performances from smaller groups, or did he just

feel happier in the smaller media?

BL: I don’t think he was

happier in the smaller media; I think it interested him more – or let’s

say it was of great interest to him. And of course most of these

things were written when he was based in Aldeburgh and they had no big

concert halls there, and no facilities to house large bodies of people.

BD: So he wrote for what

he had.

BL: In a way, yes.

Also bear in mind that what he had to work with were the top players in

the country at the time. These works – Turn of the Screw, Albert Herring, Rape of Lucretia – all have very

different orchestral parts because they were written for the players

who made up the old English Chamber Orchestra. All the harp

parts, for example, were written for Ossian Ellis.

BD: Is it special to know

that some of the vocal parts were written around your voice?

BL: Yes, of course.

He did the same thing for the singers that he did with the

instrumentalists. When I joined the company, we had a nucleus of

about eight solo singers, and he began to write for those singers.

BD: Are you happy with

what he wrote for you?

BL: Oh yes, most

certainly.

BD: I just wondered –

occasionally a piece is written for someone, and the performer later

wishes it had been done slightly (or largely) differently.

BL: Well, Ben Britten had

a better feeling for the voice than most contemporary composers.

He really did have a very good knowledge of what the voice-types would

do. So many contemporary composers that I’ve found really don’t

know. I’ve been asked on several occasions, “What is the range of

a tenor?” or, “How low will a bass sing?”

BD: Oh dear!

BL: I’m serious, and I’m

not criticizing people’s creative ability. I’m just saying that

times have changed.

BD: Those composers

haven’t spent time studying the voice?

BL: No, they just go

straight on into composing. Nowadays, as you well know,

everything has to be quick and fast. Everyone seems to be on the

lookout for new talent, and very often talent is dragged out and

doesn’t have time to develop. It’s the same with conductors and

even with singers. There was a much more steady all-round

development, and now it’s not there any more. Composers and

conductors are thrown in the deep end- particularly if they’re very

gifted.

BD: Is that the advice you’d

give, then, to an aspiring composer – to learn about the voice?

BD: Is that the advice you’d

give, then, to an aspiring composer – to learn about the voice?

BL: If you’re going to

write for the voice, yes. However, things have changed a lot in

everything in the last 20 or 30 years. In my early days of

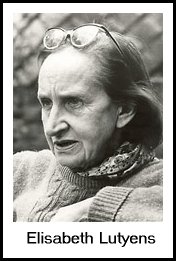

singing, I did a lot of contemporary things and I worked with Elisabeth

Lutyens, one of the great old ladies of music – one of the only old

ladies of music! Lutyens was writing music in the 1930’s, music that

was totally baffling and already much in advance (really in a different

direction) of people like Britten. She told me that when she was

first composing, she couldn’t find anyone to sing the pieces.

They were too difficult. When I was working with her she said, “I

used to be able to find the odd person who could sing it, and now there

are 40 or 50.”

BD: Are they easy to

sing, or are they things you just have to learn how to do?

BL: It depends entirely

on whether you have perfect pitch. If you do, you can just sing

whatever is put in front of you. Or, if you’re a very, very good

sight-reader, you can pretty well sing whatever is put in front of you.

BD: But these sound like

techniques rather than the ability to sing, say, a Schubert song.

BL: Yes, these are

techniques absolutely. And there are many more singers than

there used to be whose training is far superior to what it was. I

sound like a Grand-Dad here, but people, at least in England in my

generation or the generation before, just wandered into singing from

just about every profession you could name. Hardly anyone

“trained” to be a singer. It just didn’t happen. Most of my

contemporaries were truck drivers or miners or engineers, architects,

bank clerks, school teachers…

BD: And you sort of fell

into a singing career?

BL: Yes, without any real

training. And if training did come, it was rather late in life

and little bit sketchy. The generation before me had even less

training, but with the young singers now, they set out to be singers

and they go and have a very good and comprehensive musical education.

BD: Is that one reason

for the general lack of great English composers, too?

BL: I don’t know about

that. I’m happy being a singer - I wouldn’t want to be a

composer. It’s very hard. So much has been said and it’s

all been tried – effects like shouting into the piano or stamping and

kicking things, and electronics.

BD: Is any of that kind

of music really worth it, or is it just experimental?

BL: I hesitate to

say. Obviously, it’s like so many periods in art or politics or

industry. There are times when nobody knows quite the hell where

to go. This happened and is happening, and people just have to

grit their teeth. It’s the easiest thing in the world for

critics, or even people like myself, to say of a new piece, “Oh well,

yes, there’s Richard Strauss and there’s Alban Berg,” and immediately

say that the new piece is a combination, and you reel off a list of the

composers. The new composers must be terrified of that.

BD: Are there any

composers writing today whom you would put in the same league with

Britten?

BL: Well, I think he had

the best feeling for the stage. Stravinsky is a contemporary of

Britten, but he didn’t go into opera nearly as much. It seems

that so many composers lately have been writing what I call "incidental

music to a play." It makes very good theater, but I don’t know if

I would call a lot of it "opera." Arguably, one could say that

Ben Britten’s music is not always the greatest. I personally

think that Wozzeck is a much

more “modern” piece than anything that Britten wrote, but it is a

different style of writing. The whole conception is immensely

modern.

BD: Do you get a good

feeling out of performing the role of Wozzeck?

BL: Oh yes. It’s a

truly great piece, but it is very dangerous for the singer.

BD: I would think that a

lot of contemporary operas could be very dangerous.

BL: Yes, because there’s

less and less regard for treating the voice as a voice and more

interest in exploiting it.

BD: How do you guard

against being exploited, or do you simply go along with it to a certain

degree?

BL: It depends on the sort of

singer you are. It depends on how easy you find it, and those

whom I call “voice singers” are not going to be interested in modern

opera. For instance, for myself, modern opera was a sort of

gateway – as it is for many singers like me – of starting off careers

in big opera houses. Let’s face it, they wouldn’t have signed me

on for Onegin or Don Giovanni at the very beginning. If they’re

going to go for the big repertoire operas, they’ll go for the big

repertoire singers. Since my association with Britten, I haven’t

done a great deal of modern opera, and I’ve only come back to it

recently.

BL: It depends on the sort of

singer you are. It depends on how easy you find it, and those

whom I call “voice singers” are not going to be interested in modern

opera. For instance, for myself, modern opera was a sort of

gateway – as it is for many singers like me – of starting off careers

in big opera houses. Let’s face it, they wouldn’t have signed me

on for Onegin or Don Giovanni at the very beginning. If they’re

going to go for the big repertoire operas, they’ll go for the big

repertoire singers. Since my association with Britten, I haven’t

done a great deal of modern opera, and I’ve only come back to it

recently.

BD: What exactly made you

stop doing new works? Was it just that you were moving into the

"repertoire" operas?

BL: I felt there was a

tremendous amount of work for a limited return. That is being

hideously practical, but I don’t have perfect pitch and I’m not a

brilliant reader, so learning modern operas meant I had to slog my guts

out and work and work and work.

BD: You felt you could

use a role like Eugene Onegin more often?

BL: That’s right.

With a modern opera you’d do a series of 8 or 10 performances, and that

was it. I know it sounds very mercenary, but when you’re doing so

much music – and remember I’m not just an opera singer, in fact I do

almost more of everything else – I found I just didn’t have the energy

to put in the immense amount of learning these pieces required when I

knew I would only do them a very few times. I just couldn’t cope

with it, and the pieces didn’t warrant it. Very few of them lived

enough for me. Once I’d done a few performances, I’d begin to

think that’s about it. There’s not enough food in it to go on

with it.

BD: Well, all things

being equal, would you rather do Eugene Onegin or Don Giovanni rather

than Wozzeck or Billy Budd?

BL: You happen to have

mentioned four great roles. Personally I wouldn’t differentiate

between any of them. I would do any of those wherever I

could. In actual facts, it’s who you’re playing, and these four

are all immensely interesting, and that’s the interest for me in opera.

BD: Is opera, for you

then, more drama than music?

BL: Yes! In a word,

yes. However, that’s the way I approach it, and the drama is all

laid out for you by the music. Very often, it’s not two separate

things. For instance, thinking of Eugene Onegin, Tchaikovsky’s

Onegin is very different from Pushkin’s. If you try to play

Pushkin’s Onegin to Tchaikovsky’s music, quite honestly, it doesn’t

work. One has absolutely no sympathy for the man.

Tchaikovsky has softened him and romanticized him.

BD: Is that anything like

what Britten did to Peter Grimes?

BL: Yes, absolutely

right! The Grimes of the Crabbe poem is absolutely despicable and

not a creature for any sympathy at all.

BD: Do you hope to come

back to some of these parts later in your career?

BL: Oh yes, I would think

so, but I’m getting a bit old for a lot of them. My only real

regret is that I never got to do Billy Budd. It’s not done so

often and I wasn’t in the right place at the right time.

Producers tend to cast whomever seems to be doing it all over at that

time, and I never was.

BD: Perhaps other

baritones feel the same way about parts you did – such as Owen Wingrave.

BL: Well, Owen Wingrave wasn’t done much, and

I would say that the opera was not a tremendously successful

piece. The shape of it was wrong, and one most remember that it

was conceived for television.

BD: Did that help it or

hinder it?

BL: It depends on how you

look at it. It was conceived as a television piece. If he’d

wanted to write a stage opera, I don’t think he would have chosen

that. We did do it on the stage and it worked very well.

BD: Better than on the TV?

BL: I wouldn’t say

better, just different. And I think it could have worked better

on the television if the musical side of television had been as well

advanced as it is now. Producers are much more adept with opera

now. Owen Wingrave was

produced in 1971 and opera’s come into a lot more prominent position as

far as television is concerned. It’s made tremendous strides in

these last 15 years.

BD: Do recordings do justice to

theater pieces?

BD: Do recordings do justice to

theater pieces?

BL: Yes, they can.

It’s interesting you should ask that. I think that recordings do

have validity in that you can listen and make your mental eye adapt to

what the music is saying. Very often we’re being denied that in

the theater. I’ve been working in Germany a bit, particularly in

Frankfurt where every production is so “modernistic.” Often it’s

strange or even upsetting and I find that I can’t reconcile my ear and

my eye. When the music cries out for wooded dells or mountain

peaks, and all I see is a geometric structure made out of stainless

steel tubing, I find it difficult. I’m a little old fashioned and

I like to see things.

BD: One last question –

are you optimistic about the future of opera?

BL: Oh yes. I think in

the generation of top performers that is around now, there’s a sort of

coming together. And the younger generation is much more

versatile and there’s a much healthier feeling for the theater.

BD: You don’t think the

experiments are killing it off?

BL: No, not at all.

What comes shining out of all this is that there are so many fine

singers, and not so many acting/singers today. And there are also

very interesting producers moving into the opera scene. Sometimes

it’s disaster, but there’s an awareness of the stage and acting as well

as the singing which will evolve more and more interest.

=== ===

=== ===

-- -- -- -- --

=== === === ===

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on May 23,

1982,

and portions were broadcast (along with some of his recordings) on WNIB

in 1987 and 1997. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the

Archive

of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This

transcription

was made in 1985 and published in Nit

& Wit Magazine in January of 1986. It was posted on

this website in 2008. [Note: Nit & Wit was

a bi-monthly literary arts magazine published in Chicago in the

1980s.

Bruce Duffie was a regular contributor from 1984-87 and Music Editor in

1986.]

Award

- winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was an announcer/producer with WNIB,

Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

Bruce Duffie: Let me start out

by asking you about Benjamin Britten. You’ve done quite a bit of

work with his operas, so how are they different from operas by other

contemporary composers?

Bruce Duffie: Let me start out

by asking you about Benjamin Britten. You’ve done quite a bit of

work with his operas, so how are they different from operas by other

contemporary composers? BD: Is that the advice you’d

give, then, to an aspiring composer – to learn about the voice?

BD: Is that the advice you’d

give, then, to an aspiring composer – to learn about the voice? BL: It depends on the sort of

singer you are. It depends on how easy you find it, and those

whom I call “voice singers” are not going to be interested in modern

opera. For instance, for myself, modern opera was a sort of

gateway – as it is for many singers like me – of starting off careers

in big opera houses. Let’s face it, they wouldn’t have signed me

on for Onegin or Don Giovanni at the very beginning. If they’re

going to go for the big repertoire operas, they’ll go for the big

repertoire singers. Since my association with Britten, I haven’t

done a great deal of modern opera, and I’ve only come back to it

recently.

BL: It depends on the sort of

singer you are. It depends on how easy you find it, and those

whom I call “voice singers” are not going to be interested in modern

opera. For instance, for myself, modern opera was a sort of

gateway – as it is for many singers like me – of starting off careers

in big opera houses. Let’s face it, they wouldn’t have signed me

on for Onegin or Don Giovanni at the very beginning. If they’re

going to go for the big repertoire operas, they’ll go for the big

repertoire singers. Since my association with Britten, I haven’t

done a great deal of modern opera, and I’ve only come back to it

recently. BD: Do recordings do justice to

theater pieces?

BD: Do recordings do justice to

theater pieces?