RL: Not at all, no! But I certainly got myself

known as a Baroque specialist, and it’s really not true. I’m a generalist.

I’m really quite consciously a generalist, because I have a profound belief

that if you play Bartók well, you’ll probably play Bach well, or better.

And if you play Bach well, you’ll probably play Brahms better, too, and I

think there’s a very good reason for it. It’s because in studying one

style for performance and finding out how a composer puts a piece together

in his own technique and his own time, you learn something about the style

of writing and you get into the composer’s way of thinking — how he’s written

the work and how he would compose. When you then go to somebody else

of a totally different period, you find a totally different sort of ordering

of music and a totally different ordering of sounds, totally different attitude

towards the expressive power of music. Now that surely can do nothing

but widen your appreciation, not of the music itself — of course it will

do that — but also your appreciation of the ways of doing things. I

find that many, many more avenues of interpretation and of possibilities

in music are constantly being opened, even now! I’ve been at it well

over thirty years — forty years, nearly, you know. Certainly forty

years since I started.

RL: Not at all, no! But I certainly got myself

known as a Baroque specialist, and it’s really not true. I’m a generalist.

I’m really quite consciously a generalist, because I have a profound belief

that if you play Bartók well, you’ll probably play Bach well, or better.

And if you play Bach well, you’ll probably play Brahms better, too, and I

think there’s a very good reason for it. It’s because in studying one

style for performance and finding out how a composer puts a piece together

in his own technique and his own time, you learn something about the style

of writing and you get into the composer’s way of thinking — how he’s written

the work and how he would compose. When you then go to somebody else

of a totally different period, you find a totally different sort of ordering

of music and a totally different ordering of sounds, totally different attitude

towards the expressive power of music. Now that surely can do nothing

but widen your appreciation, not of the music itself — of course it will

do that — but also your appreciation of the ways of doing things. I

find that many, many more avenues of interpretation and of possibilities

in music are constantly being opened, even now! I’ve been at it well

over thirty years — forty years, nearly, you know. Certainly forty

years since I started. RL: Oh, I expect nothing out of the public, except

I hope to please them. I hope to involve them. I can’t perform

a piece unless I sense vitality in it and I rehearse an orchestra in order

to reveal as much of that vitality as I can, the amount I have come to believe

the work has. And in the performance I would hope to transmit that vitality,

that energy, that image of life — whatever it is. Whether it’s Offenbach

or Beethoven it doesn’t matter. It is what it is, and if it still has

life in it, I would hope to transmit that to an audience. If some of

them miss it, well tant pie, that’s

just tough. The more who get it, of course the better I’m pleased,

but that’s the process, I think. It’s a sort of evangelical thing,

if you like, musical evangelism. Well, it is! That’s what a preacher

does with religion. He’s trying to convey the vitality in the religion,

as he sees it, to the people he’s preaching to.

RL: Oh, I expect nothing out of the public, except

I hope to please them. I hope to involve them. I can’t perform

a piece unless I sense vitality in it and I rehearse an orchestra in order

to reveal as much of that vitality as I can, the amount I have come to believe

the work has. And in the performance I would hope to transmit that vitality,

that energy, that image of life — whatever it is. Whether it’s Offenbach

or Beethoven it doesn’t matter. It is what it is, and if it still has

life in it, I would hope to transmit that to an audience. If some of

them miss it, well tant pie, that’s

just tough. The more who get it, of course the better I’m pleased,

but that’s the process, I think. It’s a sort of evangelical thing,

if you like, musical evangelism. Well, it is! That’s what a preacher

does with religion. He’s trying to convey the vitality in the religion,

as he sees it, to the people he’s preaching to. RL: No. It is, of course, artificial in the

sense that you’re missing one very strong element, and that is audience reaction.

But that’s all right, too, because you can sort of substitute for that in

some way. You know whether you’ve got it right or whether you’ve got

it wrong, or halfway in between.

RL: No. It is, of course, artificial in the

sense that you’re missing one very strong element, and that is audience reaction.

But that’s all right, too, because you can sort of substitute for that in

some way. You know whether you’ve got it right or whether you’ve got

it wrong, or halfway in between. RL: Well, every orchestra has its own characteristics.

This orchestra has virtually no technical problems in music. They’re

to the last man stunningly good players, and also stunningly nice people

to work with. But I’ve very rarely had that experience of doing the

same program, so to speak, the next week, with a less good orchestra.

It doesn’t arise. You always try to realize the best potential that

any group has. It doesn’t matter how weak they are, or if they have

weak sections. Our job, it seems to me, is to make an orchestra, no

matter what it is, play a work with a single point of view, as near as possible.

It has to be somebody’s, so it has to be the conductor’s point of view.

You nevertheless use the vitality that everyone in the orchestra gives you,

and often you get quite creative ideas coming from the orchestra, from the

way they play, even from their spoken observations. That’s all part

of this growing-together in rehearsal that is the sign of a very good orchestral

encounter between conductor and musician. Generally speaking I find

it works wonderfully well. The musicians wish to give. They wish

to play; playing is their life. And if you’re careful for that wish

and you respect that, they’re actually on your side; they’re on music’s side,

to begin with, so then you’re all actually trying to do the same thing.

But it doesn’t matter how good they are. In fact it’s sometimes a slight

problem. It could very easily happen in Chicago, which is full of distinguished

players, that they might have some difficulties in concentrating on a single

point of view of a work. I’ve never come across it here; I don’t find

it. But you could imagine that it could be. I remember Gareth

Morris who was the first flute at the Philharmonia Orchestra — I’m talking

about thirty years ago — got across some German conductor who tried to tell

him how to play the flute solo in Daphnis

and Chloé. It’s one of those solos that’s so damned difficult

anyway that you’re lucky to have someone who can play it all! And if

you can play it as well as Gareth used to play it, or certainly as Donald Peck would play it

here, you take what you get. If there’s any problems, then you might

say, “Well, what about breathing there?” or, “Phrase that; take a little more

time, if you wish, over that,” or so and so. But to stop and sort of

dress the man down because he’s not playing as this German conductor thought

it should be played, that was a disaster! That provided a complete

frost on the whole proceedings.

RL: Well, every orchestra has its own characteristics.

This orchestra has virtually no technical problems in music. They’re

to the last man stunningly good players, and also stunningly nice people

to work with. But I’ve very rarely had that experience of doing the

same program, so to speak, the next week, with a less good orchestra.

It doesn’t arise. You always try to realize the best potential that

any group has. It doesn’t matter how weak they are, or if they have

weak sections. Our job, it seems to me, is to make an orchestra, no

matter what it is, play a work with a single point of view, as near as possible.

It has to be somebody’s, so it has to be the conductor’s point of view.

You nevertheless use the vitality that everyone in the orchestra gives you,

and often you get quite creative ideas coming from the orchestra, from the

way they play, even from their spoken observations. That’s all part

of this growing-together in rehearsal that is the sign of a very good orchestral

encounter between conductor and musician. Generally speaking I find

it works wonderfully well. The musicians wish to give. They wish

to play; playing is their life. And if you’re careful for that wish

and you respect that, they’re actually on your side; they’re on music’s side,

to begin with, so then you’re all actually trying to do the same thing.

But it doesn’t matter how good they are. In fact it’s sometimes a slight

problem. It could very easily happen in Chicago, which is full of distinguished

players, that they might have some difficulties in concentrating on a single

point of view of a work. I’ve never come across it here; I don’t find

it. But you could imagine that it could be. I remember Gareth

Morris who was the first flute at the Philharmonia Orchestra — I’m talking

about thirty years ago — got across some German conductor who tried to tell

him how to play the flute solo in Daphnis

and Chloé. It’s one of those solos that’s so damned difficult

anyway that you’re lucky to have someone who can play it all! And if

you can play it as well as Gareth used to play it, or certainly as Donald Peck would play it

here, you take what you get. If there’s any problems, then you might

say, “Well, what about breathing there?” or, “Phrase that; take a little more

time, if you wish, over that,” or so and so. But to stop and sort of

dress the man down because he’s not playing as this German conductor thought

it should be played, that was a disaster! That provided a complete

frost on the whole proceedings.|

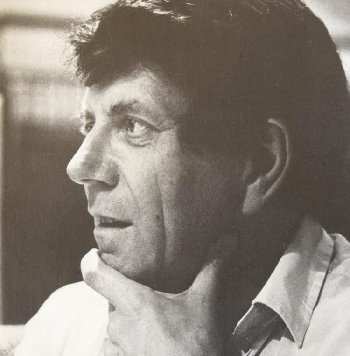

Raymond Leppard Born: August 1, 1927 - London, England The eminent English conductor, Raymond (John) Leppard, was born in London and grew up in Bath. He studied harpsichord and viola at Trinity College, Cambridge (M.A., 1952), where he also was active as a choral conductor and served as music director of the Cambridge Philharmonic Society. In 1952 Raymond Leppard made his London debut and then conducted his own Leppard Ensemble. He became closely associated with the Goldbrough Orchestra, which became the English Chamber Orchestra in 1960. He also gave recitals as harpsichordist, and was a fellow of Trinity College and a lecturer on music at his alma mater (1958-1968). His interest in early music prompted him to prepare several realisations of scores from the period. While his editions provoked controversy, they had great value in introducing early operatic masterpieces to the general public. His first realisation, Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea, was presented at the Glyndebourne Festival under his direction in 1962. In the following years he subsequently prepared more operas by Monteverdi, as well as operas by Cavalli. During this period, he made appearances as a guest conductor with leading European opera houses and festivals. In November 1969 he made his USA debut conducting the Westminster Choir and New York Philharmonic, at which occasion he also appeared as soloist in the Haydn’s D major Harpsichord Concerto. In 1973 he became principal conductor of the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra in Manchester, he position he retained until 1980. Raymond Leppard, one of the most respected international conductors of his time, has appeared with nearly all of the world's leading orchestras in his four decades on the podium. An exceptional, versatile musician who has garnered praise internationally for his orchestral and operatic performances, his talents are extensive: a prolific recording artist, with 200 recordings to his credit; an author: he has published two books; a composer: his realisations of Cavalli and Monteverdi are legendary, and he has composed a number of film scores.  Music Director of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra for the last decade,

Raymond Leppard celebrates his thirteenth season with the Symphony. Guest

engagements last season included the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, a major

tour of European capital cities with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra,

the Camerata Academica Salzburg, and L'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande.

Music Director of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra for the last decade,

Raymond Leppard celebrates his thirteenth season with the Symphony. Guest

engagements last season included the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, a major

tour of European capital cities with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra,

the Camerata Academica Salzburg, and L'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande.In February 1997 Raymond Leppard recorded two CD’s for the Decca label: a disc of all-American music of the 20th century and an all-Mozart disc with pianist Pascal Rogé. Previous Indianapolis recordings for Koss Classics include Dream Children featuring Elgar's youth-inspired music; an all-Schumann disc, Vaughan Williams' Antarctica Symphony, an all-Tchaikovsky disc and an all-Beethoven disc. Raymond Leppard has recently made two recordings with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra: Beethoven's Choral Symphony and an all-Franck disc. BBC Radio Classics have released Leppard's Mahler Das Lied von der Erde with Dame Janet Baker and the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra, with additional recordings of Debussy, Roussel, Fauré and Tippett. Raymond Leppard has an impressive list of conducting credits. He has appeared with the New York Philharmonic on seven occasions, toured with the Chicago Symphony and Detroit Symphony and has conducted many other major orchestras including Boston Symphony, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, the Israel Philharmonic, the BBC Symphony (including the Last Night of the Proms), and in all European capital cities and in Japan. In the great opera houses of the world highlights include Britten's Billy Budd at the Metropolitan and San Francisco Operas, Alceste and Alcina at the New York City Opera, the world premiere of Nicholas Maw's Rising of the Moon at Glyndebourne Opera, where he has had a long association, and performances at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden and in Paris, Hamburg, Santa Fe, Stockholm and Geneva. Raymond Leppard’s recordings have earned him such international prizes as the Deutsche Schallplattenpreis, a Grammy Award, a Grand Pro/Am Music Prix du Disque and the Edison Prize. He has composed a number of film scores including the music for Lord of the Flies, Laughter in the Dark and Hotel New Hampshire. His second book, Raymond Leppard on Music: An Anthology of Critical and Personal Writings, was published by Resources in 1993. Raymond Leppard has been honoured by The Queen with the CBE, and has received honorary degrees from Purdue University (1992), the University of Indianapolis (1991), and Butler University (1994). In 1973 the Republic of Italy conferred upon him the title of Commendatore della Republica Italiana for services to Italian music. |

This interview was recorded in Chicago on January 8, 1986.

Portions were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1987, 1992 and 1997. This

transcription was made in 2008 and was posted on this website that September.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.